The motorcycle industry, including the staff of Motorcyclist magazine, is enamored with adventure bikes. These are the SUVs of motorcycling; some of the machines are more capable than others, but they all stand tall, soak up bumps, and make your neighbors think you could leave for the Yukon at the drop of a hat. Some riders are ready to take their behemoths off-road, while others are just content with the lumberjack aesthetic.

Fresh technology and cutting-edge designs are inherently intriguing to us, but we realize that not all riders want to go to the other side of the world on a motorcycle or even look like they could. Besides that, an ADV bike equipped to make your friends jealous and your neighbor's kid go wide-eyed will set you back around $20,000. The appeal of skipping off the edge of a paved road and exploring a dusty goat path or a muddy logging road is free, and the ability to do so can cost less than a base-model Kia.

To test this theory we gathered these four affordable dual-sport machines and set out to explore the canyons and truck trails neighboring our new offices in Southern California's Orange County. All we needed was enough on-road ability to get up the freeway a few exits from our taupe-hued HQ and along a handful of small back roads that would connect us to fire roads as far as the eye can see. Over a foreshadowing ramen lunch, we elected to get in touch with our inner Scrooge and get lost without breaking the bank. Our mission: a budget backyard adventure.

European companies like KTM, Husqvarna, and Beta produce some sublime machines, but most of them are too expensive to be called "budget" bikes. "Value" maybe, but that's another discussion. So product from the Japanese big four is the obvious choice, and since economy was paramount in this test, we went straight to the back of the catalog for the quarter-liter bikes.

Along with Honda's new-for-2013 CRF250L (which won Best Dual Sport; Nov. 2013, MC), we gathered the most affordable rock-hoppers we could, first the obvious Kawasaki KLX250S and a Yamaha XT250. From Suzuki, the DR200SE is the only logical choice since the company's next step up is the $6,600 DR-Z400 (see sidebar). The same goes for Yamaha's capable WR250R; too bourgeoisie for this test.

"It's air-cooled!" one of the testers exclaimed, approaching the diminutive DR200. Yes! Air does actually work to cool an engine! And the "wee-R" was not alone, as Yamaha's XT250 is finned rather than fanned as well. Despite that, the air-cooled XT was still the most expensive bike in the test, at $5,190, with Kawasaki's KLX next in line at $5,099. Honda's 250L retails for $4,699 (up $200 from 2013, incidentally), while Suzuki's DR200 won the price war at $4,199.

With our backpacks full of granola bars, water, and dreams of Dakar, we hit the road. Being that we're knee deep in an office park, our first task was an interstate stint. Road Test Editor Ari Henning drew the short straw and rode the Suzuki, so we let the DR's 12.1ci of barely restrained fury lead the way for the first stretch of too-many-lanes-to-count I-5.

Surprisingly, the little DR did actually keep up with freeway traffic, but only just. It hits 70–75 mph with all the grace of a freshly caught fish flopping in the bottom of a boat. It felt torturous, and we simply cannot recommend DR200 freeway travel. The other three bikes fared much better, especially the Honda and Kawasaki. Yamaha's two-valve, SOHC motor was up to the task, but the XT's seat being a full 2 inches lower than the CRF and KLX made us feel more vulnerable when surrounded by traffic.

The dual-cam, liquid-cooled powerplants in the Honda and Kawasaki galloped along on the highway just fine, while long and flat seats made it no problem to find an appropriate lean angle against the wind. The KLX is geared short and coincidentally is the only one with a tachometer, which gave us a better idea of how high each of the other bikes was revving on the freeway. As nice as a tach sounds, it mostly illustrated that we didn't miss having the revs counted on bikes like these.

Mercifully we exited the rat race and wound our way, via two-lane asphalt, up into the hills. None of these bikes is designed to carve a canyon, but the Honda does so the most gracefully. Beyond stable and manageable on a twisty road, it's genuinely fun. The Kawasaki and Yamaha were close behind, and while the Suzuki suffers from being woefully underpowered, it kept up to the speed limit. It was also here that we discovered the DR200's insanely poor front brake. There's not a lot of bike to halt, but the ancient, single-piston caliper up front had us wondering if there was ABS installed (there is not).

At long last our knobby tires met dirt as we peeled off on to our first fire road. Recent rains tamed the dust, and a grand total of 72 hp among the four bikes meant minimal roost. Lack of power is the hooligan's sedative, and even our rowdier staffers enjoyed bopping along and taking in the sights. Sliding around sandy corners and leaping gently over water bars doesn't require big horsepower.

As the road got choppier, the bikes began to separate, not so much from performance but ease of use. Taller seat heights and more suspension travel on the Honda and Kawasaki—nearly 10 inches—let them float over obstacles that had the other testers posting on the pegs to navigate on the Suzuki and Yamaha. The XT's compromise to have a 2-inch-lower seat means less suspension travel, and because it's softly sprung it isn't quite as nimble over rough terrain. It's a problem that pales to the Suzuki's issue, which is that the ergonomics simply aren't designed for standing on the pegs. It's possible, but quite uncomfortable, as the pegs are too far forward and the handlebar is too far back.

Fortunately the fire roads dictated little need to post, and as we jogged down the back side of another ridge we were having too much fun to complain about any of it. Ari noted that the KLX's excellent front brake was arguably too excellent for the dirt, and he was quick to claim he didn't fall finding out. Cutting across the paved road at the bottom of the canyon, we dived gleefully toward the next set of trails and into more of a challenge than we expected. The road immediately dissipated into one path that tested our steeds much more thoroughly.

On narrow, rock-strewn single track the DR200 was quickly in over its head. It scampered along, not doing any damage to itself, but dragging undercarriage when the others did not and requiring the sit-and-paddle technique from time to time. Apart from the obvious and irreparable damage to the rider's dignity, the paddle technique worked and Suzuki's little "burro" (as Ari nicknamed it) never actually failed to go anywhere the other bikes did. It just bucked and brayed a little more than the others.

In slow, technical areas the CRF steered the slowest, and in fact is the tallest and heaviest. It's hard to call 326 pounds "big," but in this group the Honda is the only one over 300 pounds. The Kawasaki's trim figure is 26 pounds lighter than the CRF and feels that way on tight trails. But where the KLX gains agility due to less weight, it requires more concentration on shifting, with a noticeably less precise transmission, and we all agreed the curve of the handlebar brought the grips too far back.

Yamaha's XT was arguably the least intimidating among the most technical sections we tackled. A broad spread of torque and a low seat height means anyone would feel comfortable exploring. Even our less-experienced testers, however, felt the most confident on the Honda and Kawasaki despite nearly 35 inches of seat height on both.

We tumbled over hilltops, along mountain ridges, and jumped anything we saw fit during our day of cow trailing, switching bikes all along. Photo stops and water breaks were typically alive with smiles about the other guy tipping over, but also good notes. Assistant Editor James Laub pointed out that while the Honda was his favorite, it lacks a folding shift lever, which every dual sport should (and all of the other bikes do) have.

Everyone despised the Honda's fuel filler neck, too, which has bars across the opening apparently designed just to fire gasoline into riders' eyes as they fill up. We also continuously ribbed the guy on the DR200 for looking like he was riding his nephew's playbike. Yamaha's round headlight and finned motor had most of us nodding with regard to the best-looking motorcycle. Not the most modern, we admit, but a classic look, and one that best shows the intent of these bikes. Plus it has the best exhaust note.

Back on open fire roads and headed for home, we killed time venturing off the beaten path, following whims and questionable trailheads for the simple reason that the sun was still shining. A radio tower here, a burned out car there; nothing discovered that the Smithsonian would long for, but the bikes had our fire for adventure burning bright. As we lost elevation and daylight, everyone's opinions seeped into passive-aggressive coveting of certain bikes.

The pint-sized DR200 was the first to be avoided, treatment that actually started early in the day. Rolling the little drum to reset the trip meter captures the bike as a whole. See, with a bike like Kawasaki's KLR650, we forgive rudimentary facets of the machine because it can be justified by its potential to venture far enough from home that complicated electronics can hinder a trip. The DR200 has no such grandiose potential. The DR could feel much more modern and refined, without actually being any more complex to use. Or it could be incredibly cheap, but it's not that, either.

And speaking of "not cheap," none of us ever managed to forget that Yamaha's XT250 is surprisingly expensive. If it were a thousand bucks less and the cheapest bike in the test it would represent a great value, but being nearly $500 more than the CRF with half as many cams and valves just doesn't stir the soup. It's way behind the curve at a relatively premium price, and while it scrapes by with good capability and an eager character, the only real reason to have one is low seat height.

While the Yamaha batted its lovable round eyelid and smooth power curve at us, the Kawasaki sank into the shadow of the Honda. The KLX250 is a completely capable bike, with the most suspension travel and the best front brake of the group, but it falls short elsewhere. Foremost, it's carbureted and shockingly cold-blooded, requiring the choke-no-choke rain dance more than once. We were thankful to push a button, rather than have to kick it over again and again.

At the end of the day, nobody wanted to give up the key to the Honda. Although it took some lashings for little details, overall it's a terrific machine. The suspension is up for anything this side of a motocross track, ergonomics are the best of the group, and nothing in the powertrain left anyone wanting. Indeed, it got us thinking even bigger picture. Considering what a capable bike the CRF is, we all agreed we would have one instead of a CBR250R (inseam allowing). It's a great city bike, remarkably fun on twisty pavement, and offers much broader horizons than a small sportbike.

Ranking these bikes misses the point a little, considering they all delivered us successfully from the shabby hem of suburbia to full-fledged nature and adolescent levels of fun. The truth is, though, Honda's CRF250L is the standout. It's the most recently updated and benefits from Honda's obvious investment in budget friendly machines. When one tester's main complaint is that the red seat gets dirty easily, a king is crowned. It's also the only one with a fuel gauge, and that will come in handy because if you ride one you are going to want to get a dozen kinds of lost.

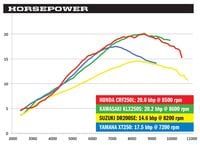

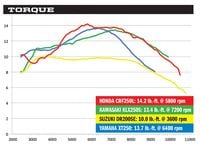

As you would assume from looking at the group, the Honda and Kawasaki lead the pack, and the Suzuki is well behind. Look at the blue line of the Yamaha, though. Up to almost 7,000 rpm it’s on par with the liquid cooled bikes. The advantage the DOHC, liquid-cooled engines have from 7-9,000 rpm is useful on the street but not as much when you’re off the beaten path. The Honda’s dip in low-end torque isn’t perceptible from the saddle; it always has your back. Over-rev is about all the underdog DR200 has going for it.

AGE: 50 | HEIGHT: 5’9” | WEIGHT: 195 lb. | INSEAM: 32 in.

Honda’s recent product line has seen success building into previously untended niches or delivering high-value options into known categories. Because of this, Honda has not straight up dominated a class for some time.

But among these four, the CRF250L is a distant first; so far ahead of the rest it’s almost scary. It performs this feat simply by being both very good and amazingly cheap. It’s refreshing that the best-performing machine of the four is also the second cheapest. It has relatively high specification in a class that still embraces the carburetor and analog speedo.

Better yet, it’s an endlessly friendly, easygoing machine perfect for those who don’t venture into the dirt as much as they should. No matter how good the other three might be—and, well, the Suzuki isn’t—the Honda kills them on value. End of discussion.

AGE: 27 | HEIGHT: 6’1” | WEIGHT: 190 lb. | INSEAM: 32 in.

When we first set out, my coworkers left Honda’s CRF250L as the last pick, and I saddled up nervously wondering what they knew that I didn’t. They must have still been half asleep because after experiencing the Kawasaki, Suzuki, and Yamaha, the choice was clear; hands down the CRF was voted MVP (most versatile pick). Honda has an extensive off-road pedigree and my time spent on the 250L proved that. And it’s nearly the cheapest of the bunch! Win. The challenge was identifying a worthy runner-up. If it were my money, I’d have the XT250 before the KLX250S. First, the KLX’s mismatched clutch/brake levers and carpal-aching bars aren’t what I want to put miles on, and second, if I want to pull a choke knob I’ll ride a vintage bike. Sorry, DR200. Stay on the back of the RV and tour the surrounding camp sites. It’s a modern world out there.

AGE: 28 | HEIGHT: 5’10” | WEIGHT: 177 lb. | INSEAM: 33 in.

It’s amazing how broad the performance and specification spectrum is here. Clearly, small-bore dual sports are viewed with varying degrees of importance, depending on the manufacturer. Suzuki has the most docile and dated offering. The “little burro” is a sweet pit bike, but it’s sized for a child and is quite anemic. The XT’s engine ranks toward the top of my list in terms of performance and character, but the Yamaha is too small as well, and too expensive for what it is. The KLX is a decent value and offers pretty good performance, but it’s fussy at start-up and the beach-cruiser handlebar sweep drove me nuts. Anyone looking to do some semi-serious adventuring should look to Honda’s CRF250L. It’s the second cheapest bike here at just $4,700, but its first in terms of features, comfort, and performance. Clearly, Honda allots the most importance to the small-bore dual-sport class.

It's no small step from these economical 250s to the next rung on the dual-sport ladder, inhabited by the Suzuki DR-Z400S ($6,599) and the Yamaha WR250R ($6,690). With the Yamaha, you get a powerful, relatively high-tech lightweight, while the evergreen DR-Z affords riders one of the most versatile machines going. The Z's displacement advantage over the 250s gives it excellent midrange torque, as handy for scrabbling up rocky hillsides as staying clear of Escalade bumpers on the freeway.

It's not the smoothest thumper in the land, and it sure could use a sixth gear, but the DR-Z's four-valve, liquid-cooled engine provides nearly the grunt of the 650s in a much-lighter package—as much as 115 pounds less, in fact. Add to that competent suspension, honest handling, and enough longevity—it's been around since 2000, after all—to have a brimming aftermarket surrounding it.

Riding the DR-Z in the company of these tiddlers is eye opening—it feels pleasantly fast, really tall, sumptuously suspended, and notably more capable than even the best-in-class Honda. It's so capable our photographer led us on one despite carrying 100 pounds of gear. Even better: $4,500 will get you a used 2011 model.

Backyard Adventure Etiquette

Words: Zack Courts Photo: Ari Henning

Exploring dirt roads, trails, and paths is a great way to take in the wilderness, not to mention making you a better and more confident rider. While you're out learning and/or sightseeing, keep in mind that it’s not your land, and the adage of “do unto others” doesn't necessarily stand with motorcycles. Just because you don’t mind ripping up your own property doesn’t mean the landowner feels the same. If the landowner is the government, as is often the case, riding like you own the place can ruin it for everyone. Luckily, there are plenty of legal places to ride. The US Forest Service, for example, has lots of information on open trails on its website. Check out www.fs.fed.us for more info, and ride safe.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OPVQ7R4EFNCLRDPSQT4FBZCS2A.jpg)