In four years, I can't remember Guy Webster ever being late to teach his high-school photography class. That alone would make him stand out a little. He was as reliable as a sunrise. We'd wander in to see him sitting at the center of a long table, like Jesus at the last supper, and when the photo class grew in size and the tables were pushed together to make a square, he managed to sit at the center of that too.

He held court there, just like he did at the coffee shop in town. Right on time, class would begin, and Guy would ask his eager students to think of the most important thing in the world for a photographer to remember.

Don’t serve red wine with fish.

We were kids. This was new.

Guy wouldn’t take a penny for his teaching, at the expense of his classes not being much about photography. Guy’s class was about what Guy liked, and fortunately those things aligned for all of us because Guy liked a million things. So there was as much talk about darkroom technique as there was about the merits of Sardinian wine, salmon, Berber rugs, and Caravaggio.

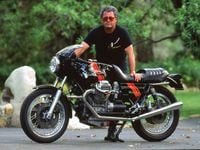

That photo class introduced everyone in it to motorcycles. Not as subjects, but as objects of art totally peripheral to photography. Every now and then the class would descend on Guy’s own darkroom on the east end of town, and inevitably the stragglers and the claustrophobic would wander up to his modest-looking red barn. It was packed with perfect motorcycles from the 1950s and ’60s and ’70s, and we’d gawk. And the most enthusiastic gawkers would be called out for it and offered 50 bucks if they went back the next weekend to dust and clean the bikes.

This would have been around the year 2000 or ’01, and there was no better or more important or more interesting collection of Italian motorcycles outside of Italy. In 1998, the Guggenheim’s Art of the Motorcycle exhibit featured five of Guy’s machines. They were beautiful, but every bike that stayed in Ojai was just as good. And if you showed up on a Saturday morning, you’d almost certainly bump into a handful of incompetent high-school kids polishing them while Guy held court again.

It’s not interesting that Guy was passionate about motorcycles. Any ape can be enthusiastic about motorcycles, and clearly, many are. They’re the kind of machines that lend themselves to propagation. Some people love motorcycles because they imbue basic transportation with the need for skill and a flair for art. Gamblers love them because, treated as an investment, the collecting and reselling of them can make you a little money. For years and years, I thought that might be why Guy had his collection, some combination of savvy and pragmatism. But when he thinned out the collection as happily as he’d built it, I started to wonder.

Guy’s bikes all dated to a wild, ebullient time in Italy. Every machine from the era seemed to be an expression of what it was like to live out from under the thumb of fascism. The “boy racers” were his specialty. Little, simple, working people’s machines that some craftsman or engineer had poured his heart into making special, like his own tiny, sputtering moonshot. And for every Ducati or Moto Guzzi that Guy restored, there was a Rumi and a Mondial and a Parilla and a Gilera and a Ceccato.

Those machines were made for young Italians to ride to work and then race on weekends; most of them were flogged mercilessly. Almost all were relegated to Italian junk heaps by the ’70s. But they’re beautiful. They’re fragile and shapely. As expressive as any sculpture ever made, and often as rare.

Try to restore a Ducati today and you might twist your hands at the expense of parts hunted down on eBay. Try to restore a 1950s Ceccato single-cam racer in the 1990s and you’d better speak passable Italian. You’d also better be ready to take a couple of flights to northern Italy to crawl the swap meets.

It took extraordinary dedication to restore just one small motorcycle originally made by hand and only ever built in the dozens, at most. When I was cleaning Guy’s bikes, he had his Ceccato racer. And he had another 74 machines just as strange and special.

That Guy loved beautiful things is no insight at all. His photographs were beautiful. His motorcycles were beautiful. Lasting, durable beauty he had all around him. He had it in his family and in his home. But thinking about Guy after his passing, I had a realization about the type of delicate beauty he sought out.

If you close your eyes and think, you can probably conjure Guy’s best-known images. He was prolific in the 1960s and early 1970s. He shot album covers for the Doors, Simon and Garfunkel, the Rolling Stones. Shirtless Jim Morrison, that was Guy. Michelle Phillips stretched out in a bathtub across John Phillips, Denny Doherty, and Mama Cass, that too. You can remember how delicate those pictures are. Just little, perfect, telling instants.

I didn’t watch Guy work often, but I remember his banter so vividly. It was impeccable, and then the next thing you knew, he had a model wearing a friend’s too-small jacket in the dead of summer. It came naturally and instantly, and it was that moment of expression when the unnatural silliness of the moment set in that Guy would find a perfect picture. Those photographs and the motorcycles and his family are a lasting legacy of an incredible, well-lived life that he shared with the world.

But what I’ve only come to admire about Guy after his passing is the beauty that he pursued for himself, for his own delight. Little ephemeral moments of joy he sought and found as gracefully in a Jack Nicholson smirk as he did in a motorcycle flea market in Turin. If you knew him, it’s not hard to imagine Guy’s satisfaction at finally hunting down and haggling for an unblemished seat for a Moto Morini Corsarino, or his delight in coaxing a raised, incredulous eyebrow from Harry Nilsson. And it’s not hard to find a little similarity in those things.

Back in that high-school photography class, it was a sure thing that someone would show up with a camera that was beautiful and fancy and new. Inevitably, it’d be misbehaving. And Guy would pick up this new, beautiful camera and twist it around in the air and look through it, like the thing was completely alien to him, and then it would instantly work. Because every time Guy got his hands on a broken machine, it would catch on that there was some great cosmic joke in the works and magically burst back to life, just for him. And then Guy would look over his glasses and tell you: I’ve found the problem. Your machine is too complicated.

I learned a million things from Guy. Some of them about photography. Some about motorcycles. As many about nonsense pairings of wine and fish. But it’s that—even with all the beautiful things in Guy’s life—he could take such delight in something so fragile as a moment I’ll learn from most of all.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)