The stories are out there, in print, online, and fresh from the mouths of folks without much of a clue. They chronicle lurid tales of wobbly, toss-you-off handling, uncontrollable third- and fourth-gear wheelies, 150-mph top speeds, and more. “This guy pulls alongside me,” you’re bound to hear. “Shifts into fourth and yanks a big stonkin’ wheelie!”

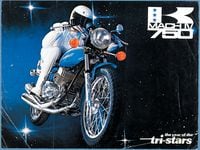

Yes, indeed, Kawasaki's 1972 Mach IV—a.k.a. the H2—was shockingly quick for its day, faster than most street riders could wrap their heads around. It ran low 12s at the strip, quicker than any streetbike in history. It wheelied too easily in first gear, surged and shook like a wet dog at certain revs, got lousy fuel mileage (high teens when ridden hard), was loud, and smoked like a chimney. Yes, the very recipe for success.

Even racers and hard-core enthusiasts of the day were anxious about the Kawasaki H2, especially those who'd ridden its peaky and twitchy 500cc little brother—the 1969 Mach III H1. "Many of us," says old-school club-racer Jack Seaver, "considered the idea of a 750cc H1 and asked, 'Are you kidding?'"

But reputation was not reality, and the original H2 was not the dangerous motorcycle popular moto-culture has so churned and embellished into epic proportions. Heck, the thing only made about 65 hp at the rear wheel!

In fact, the H2 was a reasonably competent all-around two-stroke streetbike that just happened to be the undisputed Speed King of the entire motorcycling universe, at least in ’72. Nothing went stoplight to stoplight harder or faster, or with as much visceral, mind-bending thrill, and that sort of performance made folks forget—or forgive—a lot of negatives. Which is exactly what happened in the H2’s case. Because, besides being arguably one of the two or three most legendary Japanese streetbikes of the 1970s, its raft of idiosyncrasies notwithstanding, the H2 is also certainly one of the most desirable today.

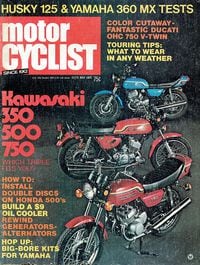

The story of the 1972 Kawasaki Mach IV H2 750 begins, of course, with the Mach III H1 of 1969, a 500cc two-stroke triple conceived, designed, and built during the latter 1960s—a time when Kawasaki, new to the US market, was looking to elbow its way in. The peaky-yet-fast H1 did its job well, catapulting Kawasaki—which had only 250cc and 350cc two-stroke twins and a 650cc four-stroke twin—to the top of the performance ladder despite the launch of Honda's refined (but heavier and slower) CB750 Four that same year. "The Mach II," wrote Charles Everitt of Motorcyclist Retro in 2008, "was pure Kentucky bourbon, straight up and without a beer chaser…designed to pack the best power-to-weight ratio available and be an absolute menace at the dragstrip, cornering performance be damned."

And the H1's cornering performance was damned…damned bad. "It wobbled at speed," remembers longtime Kawasaki test rider and race-team mechanic Steve Johnson, "and dragged its undercarriage in fast corners." Still, Team Green didn't worry much; it was out to build a performance reputation, and, at the time, brutish, arm-straightening power was the quickest way to the prize. "Finally," Johnson says, "Kawasaki had something to sell to folks wanting a big, fast, and nasty streetbike, a bike that could outrun anything out there. Kawasaki didn't even hint at handling or cornering; it was all about acceleration and top speed. When the (H1s) came out they were instantly all over the dragstrips."

Focusing on speed—not refinement or handling, which the CB750 had in spades—was a bit of a risk, but Kawasaki happily took the chance. "Kawasaki was a much bigger company and could afford to be risky," says longtime US Suzuki manager Jim Kirkland. "A friend at Kawasaki back then told me they built crazy bikes like the H1 and H2 for the publicity."

Of course, with motorcycle sales exploding and larger-bore bikes becoming more popular with baby boomers, Kawasaki was already looking for the next big thing. Or things, as it turned out. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves there…

Despite Honda's successful four-stroke four-cylinder CB750, Kawasaki knew two-stroke triples still made sense. They were narrower than fours, made more power per cc, and were lighter than similarly displaced four-strokes. Plus, Kawasaki had been developing two-strokes for some time, gaining the experience to produce eye-watering power. Finally, while the EPA had yet to clamp down on exhaust emissions, there were signs that both the tailpipe emissions and high fuel consumption of two-strokes would no longer overcome their performance advantages. But not yet.

As early as mid-1969, Kawasaki engineers conceived a bigger H1, and within months 650cc versions began circulating. Test mules were refined, with modified frames, disc brakes, and as much suspension tuning as engineers could muster. And by late 1970 a couple prototypes made their way to California for some serious testing.

As Kawasaki’s primary test rider at the time, Steve Johnson remembers that H2 prototype pretty well. “It was a 650,” Johnson says, “and it arrived with a small team of test riders and engineers. We developed a plan and headed north on Route 395 with a chase van full of parts and a spare bike. Right away, the Japanese test rider wanted to show me how fast the bike was and within minutes got pulled over for doing 120 mph-plus. The cop was pissed and wanted to haul him away but was frustrated by his near-total lack of English. I somehow talked the officer out of arresting him, and he let us go.”

A day later the group ended up on a curvy part of Interstate 80 in western Nevada. “The guy in charge,” Johnson says, “told me, ‘Steve-san, we will use this section for high-speed cornering test, and we will film you. Please ride as fast as possible!’ I’m saying, ‘You’re nuts!’ but began doing laps anyway, cutting through the median to turn around, as the nearest on-ramp was miles behind us.

“The thing had a super-tall first gear and was peaky,” Johnson says, “not as bad as the 500, but close. It wobbled at speed every time through too; I just sorta hung on and prayed. After several runs I came in. ‘Very good,’ they told me. ‘Now we do shock testing!’ This went on all day, with the camera going the whole time.”

Once back at Kawasaki’s R&D headquarters in Santa Ana, all agreed that high-speed stability was unacceptable; power delivery was too abrupt; first gear was too tall; and the brakes could be better. Six months later, another bike arrived—only this time it was a final-spec pre-production machine, not a hand-built prototype. It was also a 750. “It was much better,” Johnson says. “And more refined. Power was up and the delivery was smoother. Its gearing and brakes were better, too, and the wobbles were mostly gone. The team did a good job.”

Magazines got early test units in the fall of 1971, and the results were explosive and immediate. The bike was instantly faster in terms of quarter-mile elapsed time and top speed than anything available and was reasonably functional—the vibration, noise, surging, and mileage issues notwithstanding.

Longtime Motorcyclist editor Art Friedman tested a first-year H2 while working for Cycle News and found it funky yet functional. "It was actually a pretty good sporting streetbike despite its quirks," Friedman remembers. "It was no tourer, but it handled well and had good brakes, even when ridden hard in the twisties… And, boy, was it fast! That stuff made you forget about the vibes, smoking, and surging. It was also a great production racer. I raced several H2s during the 1970s and won a lot of races on them, even finishing sixth in an early AMA Superbike event at Laguna Seca. It was bone stock except for Dunlop K81s, Koni shocks, and a swingarm bushing kit."

Motorcyclist agreed with its future editor in its January 1972 road test, chronicling the bike's many bothersome quirks but reveling in its breathtaking speed, great brakes, and secure handling, even when ridden hard. "Handling is far better than expected and a vast improvement over the sometimes snaky Mach III," the editors wrote. "Thankfully, the 750's geometry and suspension are up to the job. With this engine a rider can be over his head with alarming frequency, yet the chassis will save him by rifling through turns without any scraping or undue waver." Although ambivalent about the H2 in many ways, the magazine capped its test report with this: "A 12-second 750 for $1,395? So what if it shakes?" If the press opinion after the launch of the H2 tells you anything, it's that Kawasaki took the criticisms of the prototype to heart and developed a much improved machine for production.

As much as any K-zero CB750, Yamaha TZ750 or ultra-rare, '68-spec TM250 Suzuki, the H2 generates an emotional connection with its baby boomer acolytes that's as fierce and memorable as any smoky, tire-squealing launch down the strip on one of the things. Suzuki's GT750 LeMans, for instance, introduced the same year as the H2, packed far more smoothness, civility, and touring capability into its two-stroke triple package but didn't sell as well as the H2 back then and isn't nearly as desirable or collectable today despite being a popular and enduring classic itself. Functional perfection (or something close to it) isn't always what endures. Attitude, impact, and a visceral connection usually do, and the H2 had that trio in spades.

Rick Brett is one of the world’s premier H2 experts and collectors, with upward of 30 examples as well as at least one of every triple Kawasaki ever made. He even consulted with Kawasaki on its wild, new H2R. “The H2 makes me smile every time I ride one,” he says. “It’s ridiculous! The thing had such a massive impact when it debuted. We all read about it and were amazed. I just had to own one.”

Dan Mazzoncini, who owns the 295-original-mile blue ’72 we photographed for this story, agrees. “I was 15 in ’72,” he says, “and known as the neighborhood motorcycle maniac. For some reason a neighbor who’d just bought a brand-new H2 let me ride it, and it literally changed my life! I bought one a year later and loved every second. I got back into them in about 1990 and have been collecting original, low-mile triples ever since. They’re amazing bikes.”

The H2 lasted just four years, from 1972 to ’75. It was a golden era for motorcycling, with unreal sales and amazing advancements in performance and reliability. The two-wheeled environment morphed radically during that time too. Kawasaki had launched its mighty, four-stroke 903cc Z1 in ’73. Smog laws, for better or worse, laid the groundwork for the end of the two-stroke streetbike era. The Arab oil embargo of late ’73 tripled the cost of oil. And more importantly, the big streetbikes of the day were becoming civil and fast, a combination the H2 certainly did not possess—even as Kawasaki embarked on a campaign to soften power and improve stability with a longer swingarm. But once a reputation is cast, it’s hard to go back.

The legacy and impact of the H2 and its four-year run lingers, like blue tire and exhaust smoke hovering above the Orange County Raceway’s Christmas-tree lights. During those crazy, On Any Sunday-flavored ’70s, the H2 was fast, daring, emotional, and, yeah, full of quirks. It remains that way today, wholly fascinating in just about every way.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)