Behind every new motorcycle is a story. Some are about the design, others the broken boundaries in the wake of the project, but often the most interesting layers of a bike’s debut are the people behind the machine. In the case of the 2020 Panigale V2 from Ducati, it’s easy to be cynical about how “new” the bike is—it’s the same monocoque frame, rear trellis subframe, and basic engine architecture as the 959 Panigale it replaces. At first glance it’s simply a new, color dash, a single-sided swingarm, and fresh bodywork to make it look more like the flagship Panigale V4. That is until you talk to Stefano Strappazzon, the vehicle project manager for the development of the V2.

He is tall and lean, with hair like a cologne model and cheekbones sitting high above a warm smile. I start by asking what projects he worked on prior to the Panigale V2, and it turns out his sportbike pedigree is fairly strong. “Before this, [I worked on the] Panigale V4 R,” he begins. “Before that, Superleggera 2, and then 959 Panigale.” That’s every pertinent Ducati machine that came before the V2, it seems, and when I ask what was before that it gets better. “I was chassis design manager in MotoGP,” he says through a thin smile. “Not the engine, but everything around the engine.” Then the Ducati press officer sitting in on our interview reveals what Strappazzon won’t: “And he won the World Championship, in 2007, with Casey Stoner.” I turn and catch Strappazzon in a bashful smile. Through a thick Italian accent and a small shrug he admits simply, “I am proud.”

It’s safe to say his time in the MotoGP paddock pays some dividends in understanding performance. As an example of the nitty-gritty development of the V2, the team measured the speed oscillation of a spinning rear tire being interrupted by traction control—imagine the “on/off” feeling a rider might get when power is cut and then redelivered. Using that data, the software was updated to rely more heavily on reading the rate of change in the spin rather than reacting to a number in a grid. The Panigale V2 isn’t the first machine to utilize this technique in its brain, but it’s a sign of diligence and pride nonetheless. As a result the system is more predictive, Ducati says, reducing the oscillations by 25 percent, and is already in use on the Panigale V4 R World Superbike. That’s the kind of thing an expert rider will feel when they ride the bike at full lean, but won’t necessarily know what the feeling is until it’s explained.

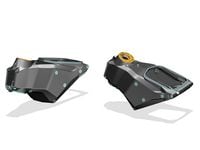

But Strappazzon quickly pointed out that building a streetbike isn’t just employing lines of sexy, racing R&D code to the ECU. Take the massive, two-canister exhaust that the global version of the 959 used (not the one imported to the US) to meet Euro 4 regulations. Ducati seemed a little embarrassed by it, and he nodded knowingly when asked about a particular challenge he faced in the V2’s design. “Mainly, the exhaust system,” he said. “To make something beautiful, small, and compact, but still remaining within the emissions standards. Euro 5 is more restrictive in terms of pollutant emissions, not for noise emissions,” he explained, “so we tried to keep the same noise while making the silencer smaller.”

As glorious as his MotoGP job was, he is clearly interested and motivated to solve seemingly mundane problems too. “We did a lot of work on the internal layout of the silencer in order to keep the dimensions very compact but also very clean,” he admits. “It’s one of the biggest efforts we put into the bike.” And just like that countless hours were spent on a muffler, testing different combinations of catalytic converters and packaging it to fit without looking terrible. All of this is why it takes three years to build a new motorcycle, especially one that has deeper layers of electronics and sophistication than ever in a “middleweight” machine.

Putting aside the spreadsheets, government guidelines, and ECU programming, I ask about Strappazzon’s favorite piece on the V2. What piece would he hang in his kitchen to look at every day? It turns out it’s a piece of cast aluminum that is entirely shrouded and hidden by bodywork and components as the bike sits in a showroom. He says quickly, “For sure the monocoque,” then backpedals with a laugh. “The Superquadro engine is difficult to put in a kitchen.” He explains that that chunk of aluminum holding the machine together—as well as essentially acting as the airbox—along with the engine are the two things that he feels define the baby Panigale.

As for working on streetbikes instead of cutting-edge racing prototypes to take on the world, he’s diplomatic. “I like them both,” he says, “it’s difficult for different reasons.” As with any competitive mind, he can’t help but go back to the satisfaction of creating something to help people go fast. “With a racebike, it’s nice because if the bike performs well, you see the result of your work almost immediately,” he explains. “With a road bike, you work for many years on a project before the launch of the bike, and to see if it will be a success.” Time will tell if the Panigale V2 performs up to his expectations. Until then he’s already on to writing the story of another new machine. And that, he says with a smile and a shake of his head, he cannot talk about.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)