Intentionally or not, Ducati made displacement a big deal when it released the 899 Panigale, even coining a new term—"supermid"—to classify this bike. The idea of a supersized middleweight blending the agility of a 600 with the accelerative thrust of a literbike is nothing new. A decade ago, 750cc was the definition of superbike. But displacement inflation has since bloated superbikes to 1,000cc and beyond, and 750s have all but disappeared. (Except for Suzuki's GSX-R750, which lacks the electronic sophistication of today's top-line sportbikes, explaining its exclusion from this comparo.)

What goes around comes around— enter the supermid. Like so many modern motorcycle trends, this one is driven by European brands that aren't afraid to flout convention. Triumph's category-defying Daytona 675, powered by a unique, 675cc inline triple, was the first and instantly established itself as one of our all-time favorite performance bikes. Legendary Italian manufacturer MV Agusta followed next, knocking off Triumph to create its first middleweight sportbike, the 675cc, inline-triple F3. This year the F3 has been upsized to create the more powerful, smoother-running F3 800.

Similar displacements and the same country of origin make comparisons between the F3 800 and 899 Panigale—a more affordable and accessible version of the 1199 Panigale superbike—inevitable. Rather than the predictably obvious MV/Ducati shootout, however, we decided to do something different. We would like to compare the two new bikes to each other, but we also wanted to test the fitness of the supermid concept at the same time, to see whether this best-of-both-worlds promise held up. So we collected the 899 Panigale and F3 800 then bracketed these with the top-of-the-line R version of the aforementioned Daytona 675, as well as one of our favorite literbikes, Aprilia's fast and charismatic RSV4 R.

We hoped this strategy, riding two unknowns alongside two known quantities on the street and racetrack, would broadcast any advantages or defects of these similar-yet-disparate machines in high definition. These four bikes might seem dissimilar on paper—a V-twin, two inline triples, and a V-4, with displacements ranging from 675 to 1,000cc—but all in their own way defy convention in an attempt to achieve some perfect performance ideal. And the truth is the prices aren't that different, with a range of $13,499 (Daytona 675R) to $15,798 (F3 800). Comparing all four would reveal how successful (or flawed) each is in this quest and, depending how the 899 and F3 800 stack up, the merit of the supermid concept would be revealed, too. Is this just another passing fad or a legitimate formula here to stay?

We'll start with a closer look at the bike that started this discussion, Ducati's 899 Panigale. More than just a sleeved-down version of the 1199 Panigale superbike—along the lines of the previous 748/749/848 middleweights—the 899 is intentionally designed to be a better streetbike, with specific technical and material changes to make the bike more accessible to more casual riders. Less oversquare engine geometry, milder cams, and smaller throttle bodies knock the sharp edges off the Superquadro engine, while a steel subframe, aluminum (not magnesium) engine covers, narrower rear wheel with a 180 tire, and a conventional, double-sided swingarm drop the price to a Ducati-cheap $14,995.

The Minigale is a better streetbike than the 1199; in many ways, it's the best streetbike of this bunch. It's certainly the most comfortable—who thought we'd ever say that about a Ducati?—with an unexpectedly soft saddle, ample legroom, and high, wide handlebars that enforce a more upright riding position. The smaller Superquadro produces a healthy 128 peak horsepower, but just like its big brother, it feels soft at low- and mid-rpm with a noticeable power spike around 7,000 revs—not a typical V-twin powerband, though it feels properly fast when you keep the revs up.

Peaky power delivery is not a problem for the MV Agusta or Triumph, both powered by inline triples that credibly combine the low-end thrust of a traditional twin with the high-rpm rush of a traditional inline. The triple powering this latest Daytona is Triumph's best one yet, revamped last year with 2mm more bore and 2.7mm less stroke, dual fuel injectors per cylinder, a lighter valvetrain, and larger airbox, raising redline to 14,400 rpm and boosting output to 119 hp. Perfectly calibrated fuel injection enhances drivability while strong low-end power, a lighter crankshaft, and lower final gearing helped the Daytona get the initial jump on the bigger bikes during impromptu highway roll-ons.

The latest D675 enjoys other updates in addition to the new engine. Switching from an underseat to under-engine exhaust saves weight and centralizes mass, while a new frame and swingarm with less wheelbase and more aggressive front-end geometry hones already sharp steering. The premium-spec R version tested here further benefits from exceptional Öhlins suspension (a TTX shock and NIX30 fork), Brembo monoblock brakes, a seamless quickshifter (all four bikes are quickshifter-equipped), and some gram-shaving carbon-fiber bodywork.

Although it looks and even sounds similar to the Triumph from a distance—both bikes are white with red trellis frame sections—MV Agusta's F3 800 is its own machine and a better bike than the original F3 675 in every way. The longer-stroke (8.4mm longer than the F3 675, with the same 79mm bore), 798cc triple not only makes more torque (peaking at 58 pound-feet) but also builds revs more evenly than the hyper, hard-to-manage 675 version. The dyno curve is impressively smooth, building strong, consistent power from the basement to redline, where it finishes with a howling top-end rush just like MV's 1,000cc F4.

The feel from the cockpit inspires more Triumph comparisons. Both bikes feel tall and narrow between the knees, though the F3's riding position is more comfortable; the Triumph saddle seems slightly too close to the footpegs, cramping your legs. MV's novel frameset, combining cast-aluminum centers with a steel-trellis front section, delivers a perfect combination of rigidity and compliance. Handling is overall very good, with quick, precise turn-in manners and neutral steering at any speed or lean angle, though the Marzocchi fork setup feels a bit harsh, somewhat degrading front-end feedback.

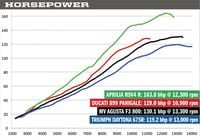

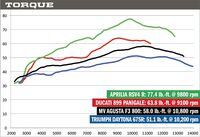

In terms of horsepower, the triples and the V-twin are at least in the same chapter, if not on the same page, with just under 11 hp separating the little Brit bike from its Italian brethren. Aprilia's RSV4 is another story entirely. That bike's 164-hp output towers over its nearest competitor here, the 130-hp MV Agusta. A highly refined electronics platform—more on that in a moment—makes all that power surprisingly easy to control, and a chassis package proven on the World Superbike Circuit inspires confidence at any pace. The question remained—would the exceptionally well-balanced RSV4, a former WSBK champion and "Class Of" comparison test winner, outshine as an overdog or be at a disadvantage against its lighter, more manageable supermid competition?

We took to the streets to find out, escaping the beige void of our Irvine office park for the technicolor glory of California Scenic Highway 74—the famous Ortega Highway—up and over the Cleveland Mountains then down into the Coachella Valley. The open, relatively upright Ducati quickly established itself as the favorite streetbike, and the best antidote to the excess wrist stress inflicted by the Aprilia's tall-tailed, stinkbug riding position. Our enthusiasm for the 899's street manners was damped only by excessive exhaust heat and a slight off-throttle abruptness—perhaps ride-by-wire indecisiveness—that made the 899 anxious in traffic on the highway.

Exiting the expressway and riding toward Lake Elsinore shifted our perspective somewhat. Fast, on-camber, uphill sweepers favored the on-point geometry and aggressive riding positions of Aprilia and Triumph, and the Daytona's superlative Öhlins suspension—head-and-shoulders above anything else here and so easy to interpret—demonstrated a clear advantage. The Daytona always feels composed and fluid—that mythical combination of stiff support and compliant response that you only get from high-end, well-developed components. The other three bikes felt harsh by comparison, particularly the Ducati, the stock settings on which are quite stiff.

The descent to Palm Desert presented our first meaningful opportunity to experience the braking ability of each bike, and more contrasts emerged. Ducati's flagship 1199 Panigale, fit with Brembo's ferocious M50 monoblock calipers, stops with almost violent force; the 899 delivers milder, easier-to-modulate braking response from its combination of Brembo M4 calipers and less aggressive pads. The flip side is the F3 800, which stops with the authority we expect from the best European sportbikes. Some testers found the MV binders overwhelming for the street, but such steel-trap stopping power was appreciated during the two-day track test at Chuckwalla Valley Raceway.

Like most modern sportbikes, all four are equipped with some manner of electronic rider assists including, in most cases, traction control and ABS. Although you rarely engage these electronic overrides at typical street riding pace, where they stand in reserve as emergency safety nets, the importance of effective electronics rises to the forefront at the racetrack, where optimized conditions allow you to safely and consistently approach the limits of acceleration, braking, and lean angle. All four bikes seemed relatively closely matched on the street, all capable of achieving what could reasonably be considered a maximum sensible back road pace. The wide-open racetrack, on the other hand, put these four machines—especially the effectiveness of the different electronics platforms—into sharp relief.

The Daytona 675R is the least expensive, least powerful, and least sophisticated motorcycle here, equipped just with ABS. "No ride modes, no TC, no B.S.," Cook says. Realistically, the Triumph doesn't need anything more. Throttle response is so seamless, power delivery is so smooth, and the rear wheel is so well controlled that even when it did spin up it was easy to reign in manually. Switchable Nissin ABS offers three settings—off, on, and Circuit, the latter deactivating the rear ABS to allow drifting and lifting and also backing off the activation threshold for the front wheel. The default setting is too bossy for the racetrack, but the Circuit setting could only be detected during the hardest stops at the bottom of Chuckwalla's only downhill braking zone, announcing itself with just the gentlest pulsing at the lever.

All that energy manufacturers expend trying to design the ultimate digital dash is wasted on us. We prefer old-tech but always-easy-to-read analog tachometers like those found on the Triumph and Aprilia (top left and top right, respectively). The MV’s digital display (bottom left) is crowded and over-complicated, incorporating everything but the one thing that you really want—a shift light! The 899 lacks the 1199’s sophisticated TFT display, but at least it’s straight-forward and easy to navigate.

We've already said all there is to say about Aprilia's Performance Ride Control; it remains one of the most effective, least invasive systems we've ever sampled. Traction and wheelie control are perfectly integrated and work together seamlessly to maximize lap times, and the activation is so transparent that you don't feel it—which is kinda the point. Aprilia earns major bonus points for on-the-fly adjustability via huge thumb and forefinger paddles—we wish every bike was equipped like this.

Ducati Traction Control (DTC) has likewise been discussed ad nauseam on these pages, and nothing has been lost in the translation to the 899. Three ride modes—Wet, Sport, and Race—alter power output, throttle response, traction control, and ABS intervention to suit, and ABS and TC intervention can always be tailored separately, the latter to one of eight settings. And unlike some systems, changing DTC levels actually results in meaningful changes you can feel at the wheels. Engine braking is three-level adjustable as well. In practice, the "margin of wheelspin tolerance" allowed in the lower TC settings on the track seemed suitably generous, functionally transparent, and conducive to quick lap times.

That leaves the F3 800, equipped with the most complicated—if not sophisticated—electronics platform in this group. MV's Motor & Vehicle Integrated Control System (MVICS) offers the choice of three individual engine maps (including one that can be customized by the owner), eight-level-adjustable traction control, adjustable engine braking, even two rev limiter settings. Unfortunately, MVICS is difficult to master and control with its hidden menus and maddeningly vague switchgear, and, worse, alarmingly incompetent in application.

MV Agusta engineers apparently spent more time specifying settings than tuning settings because, with few exceptions, none of the settings work as intended. MV Agusta reps explained that TC intervention is informed by pre-programmed "grip curves" calibrated for "street tires and street conditions;" in our experience rendering the system essentially useless—dangerous even—at the racetrack. MVICS cut power at the most inopportune times, when traversing bumps, changing direction, or picking up the throttle at a downhill corner apex—where it presumably misinterpreted the combination of increasing wheel speed and closed throttle as wheelspin. When the manufacturer's rep says it's best to ride the bike with traction control deactivated, that's a clear sign the system isn't ready for prime time. Ironically, even though it has the strongest brakes, the F3 is the only bike here without ABS. Given how glitchy the other electronics are, though, this is probably a good thing.

Perhaps predictably, the bike we liked the most on the street fared the worst at the racetrack. Ducati's 899 Panigale turned the slowest lap (1:53.14), hampered by numb brakes and some ergonomic complications. The skinny midsection afforded by the "frameless" chassis makes the bike feel light and compact, but it's hard to hold onto and leaves nowhere to anchor your body when hanging off. This situation is complicated by slippery footpegs that are low-mounted and quick to drag, compromising cornering clearance and corner speed. Suspension action from the Showa Big Piston Fork and unmarked Sachs shock was also a bit harsh over Chuckwalla's many bumps and occasionally unsettled the chassis, causing the 899 to pitch forward and back if you weren't hard on the brakes or gas. Where the 899 disguised its cost-savings well on the street, the bargain-based component choices were exposed at the racetrack.

With the smallest displacement, it's little surprise the Daytona 675R turned the third-slowest lap, at 1:52.52. In fact, it felt noticeably slower on Chuckwalla's two short straights, lacking the headlong rush of high-rpm acceleration that typifies the other three machines. Despite this power deficit—and even without the benefit of traction control—the Daytona was a favorite at the racetrack. Much of this impression owes to the amazing Öhlins suspension, so effective at neutralizing bumps and erasing mid-corner drama that Chuckwalla felt like a different and better racetrack aboard the Daytona. An exceptionally balanced chassis and dial-a-lean steering, flawless throttle response, athletic ergonomics, and a dependable quickshifter make the 675R the easiest and most confident bike to ride at speed.

Also operating without the benefit of traction control—deactivated for our safety—the F3 800 managed a nearly identical best lap of 1:52.49, by the sheer grace and gift of Young Master Courts' finely calibrated throttle hand. Lightning-quick steering helped here, as did equally ferocious braking and accelerating abilities (and despite a balky transmission that frequently failed to shift from third to fourth gear). We can only wonder how much an effective traction-control system like DTC or APRC or race-grade ABS like Triumph's might further shave off lap times. A steering damper would be a nice add too—the F3 800 occasionally exhibited a nasty headshake during quick transitions when hard on the gas.

In the end, however, there's just no substitute for brute horsepower. Even on a claustrophobic track like Chuckwalla, where the over-geared, 164-hp Aprilia RSV4 R could barely get out of third, it still turned the fastest outright lap at 1:51.98. Time-distorting acceleration, accurate steering, and acceptably firm suspension all helped achieve such excellent performance. Trustworthy traction control that allows an obscene amount of rear-wheel slip so you can safely square off corners is necessary, too, because a bike this big can't carve a line like the Triumph or Ducati can. It was interesting to ride this 473-pound superbike, which we'd previously applauded for "hiding its heft so well," alongside such lighter, more lithe machines. The RSV4 R felt noticeably bulky in this company.

Choosing a winner from this decidedly mixed litter is more complicated than usual. Which is the best all-around sportbike? The awesomely overpowered literbike with the sophisticated electronic rider assists that still make it easy for anyone to manage? The underdog 675cc triple so superbly balanced that it can almost ride circles around larger, more powerful competitors? Or is it one of the supermids, theoretically splitting the difference? Ultimately, neither of the two supermids quite satisfied. Both more or less delivered on the performance promise, offering impressive power and agile handling, but neither is the complete package: cost-cutting component specifications undercut the Ducati's true potential, while underdeveloped, ill-conceived technology is MV Agusta's undoing.

Then there's the issue of economics—where this discussion gets truly interesting. At $15,798, the MV Agusta F3 800 is the most expensive bike here. With its exotic styling, legendary heritage, and top-tier fit-and-finish that's to be expected—even justified. But beta-stage software development, the balky transmission, and outright flaws like a gear indicator that couldn't see sixth gear are unacceptable at any pricepoint, especially this one. It might be the best MV in recent memory, but that's not saying enough. Like many exotics, this bike is built for someone with more money than sense.

Ringing in at $14,999, the Aprilia RSV4 R ABS is probably the best value of this bunch, especially considering its performance. Yeah, the Sachs suspension isn't as amazing as the Öhlins suspenders on the $19,999 RSV4 Factory SE, but it's certainly not $5,000 worse! Meanwhile, the APRC electronics, the super-powerful, super-flexible V-4 engine, and that hair-raising exhaust note are identical. So it's thirsty, and it's impossible to find neutral, and your closest dealer is probably 500 miles away—get over it. If you're an expert who wants a big-ass-powerful Italian superbike but doesn't need to be seen on a Ducati, this is your ride.

If, on the other hand, you're not an expert, you don't want a big-ass-powerful superbike, or you do need to be seen on a Ducati, the $14,995 899 Panigale will suit your needs. This is a great value if you value the Ducati name, delivering nearly as much style as the 1199 version with more accessible performance for less experienced or more casual street riders. It's a much, much better streetbike, for instance, than the 1199 Panigale R that is twice the price! It's remarkably comfortable for a dedicated sportbike and undeniably gorgeous to look at, still nicely built despite all the plastic and other evidence of cost cutting. It didn't live up to the Ducati name at the racetrack, but it wasn't built to win racing championships. No doubt Ducati is at work now on a more expensive R version better suited for that.

It's not often that the cheapest bike is the best bike, but the $13,499 Triumph Daytona 675R is. That's not to say it's a cheap bike—Öhlins equipped, with big Brembo brakes, and lots of carbon-fiber eye candy, it's very much a premium machine. And it just plain works—the chassis is perfectly balanced, handling is telepathic, power is strong and easy to exploit, so much so that it transcends its displacement station. That it does all this so well and also delivers a strong dose of character, with that growling exhaust note and heady gear whine, is just more sugar. It turns out that it's Triumph's Daytona 675R that puts the "super" into the middleweight class.

Zack Courts | Associate Editor

AGE: 30 | HEIGHT: 6'2" | WEIGHT: 185 lb. | INSEAM: 34 in.

This whole "supermid" thing reeked of marketing to me, but I will confess that both the Ducati and the MV impressed me by feeling small and punching hard. The MV especially, which delivers a wonderful rush of power (and has stellar brakes, incidentally). However, typical MV gremlins abound; the seat and mirrors suck, the gear position indicator gets confused, and traction control doesn't work, to name a few. Ducati's 899 suffered from numb brakes on the track, but as a streetbike it's surprisingly agreeable. Better than an 1199, that's for sure. The baby Superquadro mill sounds great, but I still don't like it; I want torque from a V-twin, not revs.

What this test really taught me is that I don't want a supermid; I want a super or a mid. Triumph's Daytona 675R is sublime, but I wouldn't be able to resist splurging a little for Aprilia's RSV4. No, I don't mind the tall saddle; I'd sit on a seat of rusty nails if Aprilia's V-4 was bolted underneath.

Ari Henning | Road Test Editor

AGE: 29 | HEIGHT: 5'10" | WEIGHT: 171 lb. | INSEAM: 33 in.

As far as the "supermid" concept goes, the F3 800 does it best. Its motor is more powerful and easier to manage than the F3 675's, and the handling is just as good—the 800 only weighs 5 pounds more, after all. Too bad, then, that the package suffers from the same awful traction control and asinine interface that afflicts all of MV's sportbikes.

Having endured sore wrists and a heat-rashed backside on the Panigale 1199, I was wary of the 899. But Ducati did a tremendous job of improving the bike's streetability. With its lower price, better manners, and overall impressive performance, I expect Ducati will sell a lot of 899s, but I'm not buying. Compared to ultra-refined and capable bikes like Aprilia's fire-breathing RSV4 and the Triumph 675R, the Duc doesn't stand a chance.

In the end, though, I'm a sucker for the sweet song of a Triumph triple, and the R-spec Daytona is simply one of the best sportbikes money can buy, regardless of displacement.

Marc Cook | Editor in Chief

AGE: 50 | HEIGHT: 5'9" | WEIGHT: 195 lb. | INSEAM: 32 in.

This comparison reminds me of the whole turbo thing in the 1980s. They were supposed to provide the brutish power of big bikes while retaining the lithe handling of true middleweight machines. Didn't happen. Instead, we got bikes as heavy as literbikes with hard-to-manage power just above a good-running 850.

Today's supermids promise the same thing: big power, small package. But here's the problem: In the form of the Ducati 899 and the MV F3 800, supermids are indeed stronger than traditional middleweights but nowhere near the forearm-straining, ass-clenching brutality of Aprilia's magnificent full-liter V-4. Yes, I love that engine, irrationally so; and, yes, I adore the RSV. The RSV is close enough in weight and agility that I'd gladly accept a compromise for that glorious V-4 soundtrack.

I would be sorely tempted to drop coin on the Triumph, largely because it has the best balance of thrust and precise handling and finds the true sweet spot of light-bike agility and ability to inspire confidence. Plus that triple sounds great and makes enough thrust to keep me happy on any street ride. The supermid promise? Not yet fulfilled.

Aaron Frank | Editor at Large

AGE: 39 | HEIGHT: 5'7" | WEIGHT: 155 lb. | INSEAM: 31 in.

As a longtime lover—and two-time owner—of Suzuki's GSX-R750, I especially appreciate the appeal of this "supermid" concept. But the truth is, none of these bikes match the perfect balance of power, handling, and all-day rideability that either of my lightly tuned Gixxers delivered. Triumph's Daytona 675R—plus another 15 hp—would come close. So might Aprilia's RSV4 R, minus 50-odd pounds.

Until then, I'm going to do something I usually loathe doing—I'm going to select a hypothetical hybrid to win my own private comparison. Despite its many shortcomings, I still fell hard for MV Agusta's F3 800. That wicked triple is so soulful and strong, the handling is on-point, and it's a pleasure to eyeball, too. Give me that bike, only with the 675R's magic-carpet Öhlins suspension and the RSV4 R's unflappable electronics package. Oh, what the heck, throw on Ducati's comfy seat, and paint it red, too. That would be a supermid worth talking about.

In order to accurately compare our testbikes' handling and performance, it was imperative that they all be on the same tires. For that we turned to Pirelli and its Diablo Rosso Supercorsa SC V2s (Special Compound Version 2) DOT-approved race rubber—the same buns that are winning championships all over the globe.

All four of our testbikes came from their respective factories shod with the Italian firm's goods and took to the race rubber amicably, displaying quicker turn-in and improved feel and stability at full lean. Pirelli is constantly refining its products and made some major changes last year, including an updated carcass, new tread compounds, and a new, repositioned "single element" tread design that increases the slick area on the shoulder (by 24 percent, says Pirelli) for better traction at appendage-dragging lean angles.

Of the many sizes and compounds available, we went with a standard 120/70 soft-compound front and medium versions of the latest 180/60ZR-17 rears on all but the RSV4, which took a medium-compound, 200mm-wide tire. CT Racing's Chris McGuire was on hand to bust beads and monitor tire pressures, ensuring we got the best performance from the tires. Indeed, the tires offered all the grip we could use and lasted all day, even on the 163-hp Aprilia.

Supercorsa race tires are only available through race distributors for $175–$188 for fronts, $186–$256 for rears. The Western US is supported by CT Racing (ctracetires.com), while the eastern states and Canada are supplied by Orion Motorsports (orionmotorsports.ca). —Ari Henning

None of these bikes are all-day comfortable, but the Ducati genuinely surprised us with a soft seat and ample legroom. The MV has more measured legroom, but it doesn’t feel like it; maybe the rock-hard seat and engine heat distracted us. Like the MV and the Ducati, Triumph’s 675R has a slim waist. A comfortable seat helps, but low-slung, angled clip-ons feel severe on the street—good thing the suspension does such a fine job taking the edge off bumps. The RSV4 is the quintessential sport bike, with a committed riding position, a firm seat, and wide, low clip-ons. However, it fit all of our testers—from 5-foot-7 to 6-foot-2—remarkably well. Our only real complaint was engine heat thrown on our ankles, but that’ll happen with 163 horses on tap.

No surprise here: the RSV4 rules the dyno chart. More cylinders and more displacement put the Aprilia in the lead across the board. Torque drops and power delivery levels off slightly be-yond 10,000 rpm, but you’d never know it from the saddle! Displacement helps the Panigale as well, but the Ducati doesn’t dish out power in typical V-twin fashion—the Superquadro engine feels soft down low then hits hard beyond 7,000 rpm. Both the triples plot beautifully smooth curves and the larger, 798cc MV edges out the 675R everywhere, but perfect fueling and appro-priate gearing let the Triumph punch way above its weight.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OPVQ7R4EFNCLRDPSQT4FBZCS2A.jpg)