Standard-style motorcycles get a bum rap. Start with that name: Nothing sounds as blasé as "standard." Where's the emotion in that? "Naked bike" sounds a lot sexier, and "streetfighter" is almost as provocative, even it it's not dripping with innuendo.

Which brings us to the two motorcycles shown here: the Honda CB1000R and Kawasaki Z1000. Universal Japanese Motorcycles, yes—but from which universe? A parallel one? Maybe Otherworldly Japanese Motorcycles is more fitting?

Ducati and Triumph get credit for inventing the naked bike and streetfighter, respectively (see page 54), but one could argue that Honda got the ball rolling with the original 1969 CB750. That was the first across-the-frame, four-cylinder production streetbike, and it laid the groundwork for all that followed. Kawasaki upped the ante with its 1972 903cc Z-1, arguably the first superbike. It wasn’t until decades later, when British punters began stripping the fairings off their crashed sportbikes because they couldn’t afford to replace them that the naked bike/streetfighter came into vogue.

For some inexplicable reason, however, Japanese nakeds have never caught on in the USA. Honda tried twice: first in the 1990s with its CB1000 “Big One,” and again in the 2000s with its 919. Neither sold well, and both were quietly discontinued. It took Honda Italy to bring the CB1000R to market (in fact, it’s built there), but it took from 2007 to 2011 before American Honda decided to bring it stateside.

Kawasaki has stayed at it longer, offering a line of retro-styled Zephyrs that included the ZR1000 in the ’90s before debuting the Z1000 in 2003. The third-generation model shown here was developed in conjunction with the new Ninja 1000 (with which it shares its underpinnings), but the Z saw the light of day first, in 2010, due to popular demand in Europe.

Both the Honda and the Kawasaki are radical by Japanese standard standards. With its sexy lines, stacked projector-beam headlamps, single-sided swingarm and integrated under-engine exhaust, the CB1000R looks very European—not surprising, given its lineage. Though Honda was the first major manufacturer to put a single-sided swingarm into production, licensing the design from the French Elf roadracers, most enthusiasts give credit to Ducati, so the CB owner can expect to have to defend his bike’s honor!

The Kawasaki, meanwhile, looks distinctly un-European, and more like a prop from a science-fiction movie. Transformers, anyone? Originally offered in a hideous burnt-orange with a plain-white gas tank, or a slightly better-looking black-with-silver, the Z was "murdered-out" for 2011 with a black-on-black scheme that looks seriously badass.

Throw a leg over either of these bikes at night and the first thing that grabs your attention is the colorful instrument display: blue on the Honda, orange on the Kawasaki. The CB’s is electronically adjustable for intensity; the Z’s physically adjustable for angle via a two-position pull knob. Both feature a numeric speed readout and bar-graph tach, the former far easier to read than the latter.

Fire up either bike's motor and you're greeted with a familiar four-cylinder whir, the Kawi's a little more mechanical-sounding. Blip the throttle and the revs zing right up, though if you close the throttle and whack it open again, the Kawi has a delay meant to prevent raw fuel from being dumped into the catalytic converter. Pull in the hydraulically actuated clutch, snick the six-speed transmission into first gear, and here the Honda gets your attention with a loud "clop." Clutch engagement is smooth and progressive on both bikes, although the Kawi's clutch became noticeably grabby after we ran it at the dragstrip. Replacing the friction plates helped, but we should have replaced the metal plates as well.

Speaking of performance testing, the Kawasaki cleaned up in every aspect, producing the biggest horsepower and torque figures, plus the quickest quarter-mile and top-gear roll-on times. That’s to be expected, given how strong its motor feels, but the Honda ain’t no slouch, particularly once you add corners to the equation.

While the Z1000 isn’t exactly ungainly, it does take a little more effort to hustle through the twisties. Like many of Kawasaki’s sporting streetbikes, the Z hunkers down on its suspension in the interest of straight-line stability. All suspension is progressive, whether it has progressively wound springs or not, and riding that far down in the stroke, the Z’s fork and shock feel harsh, particularly over square-edged bumps. Adding preload puts them higher in the stroke, where the ride is cushier. That sounds counter-intuitive, but it’s true.

The Honda, by comparison, has softer springs with more preload, which lets the suspension ride higher in its stroke for better small-bump absorption. The softer springs also let the bike pitch forward under braking and entering corners, effectively reducing rake and trail and easing handling. The downside to those soft springs is a rough ride over bigger bumps and while braking on rippled pavement.

The brakes on both of these bikes are superb, by the way, with excellent feel and stopping power—which makes sense considering they both use Tokico components. What is surprising is that while both bikes use Showa suspension components, the Honda features a 43mm fork and a shock with a 10-position stepped preload adjuster while the Kawi gets by with a 41mm fork and a shock with a stepless, threaded preload adjuster.

While both the CB and the Z have agreeable riding positions—fairly upright with ample legroom and at least some hint of wind protection—neither can truly be called comfortable, for a reason that’s not apparent in the dealer’s showroom: excessive vibration. Rev either one beyond 4000 rpm and the bars, pegs, seat and tank vibrate annoyingly, blurring the images in the rear-view mirrors. The Honda’s is more of a coarse buzz, the Kawi’s a higher-frequency tingle, but they both get old, and can put your hands to sleep on long rides.

A note on that subject: The Honda scores a minor victory here in that its gas tank is a half-gallon larger, letting it go 15-20 miles farther than the Kawi. Neither bike goes particularly far on a tankful, however, as their low-fuel lights routinely illuminated with little more than 100 miles showing on their tripmeters. On a related note, filling up the Honda is complicated by a metal pipe that bisects the fuel tank opening; presumably part of the vapor-recovery system.

That’s picking nits, however, and the truth is these are two very fine motorcycles. Any rider could truly be happy on either one, and given that they’re priced within a few hundred dollars of each other, cost isn’t a factor. The most surprising discovery in this comparison is how different two seemingly similar four-cylinder sporting standards can feel.

The Honda, as is often said about Big Red’s products, is a model of refinement. Its fit and finish are a cut above the Kawasaki’s, or any other maker’s save for some boutique European brands. Smaller, lighter riders—particularly those moving up from a middleweight motorcycle—would do well to consider the CB1000R. It defines the term “user-friendly.”

The Kawasaki, in best Team Green tradition, is all about its engine—it’s brute force on wheels. It’s not for the faint of heart, nor the inexperienced. The Z1000 is aimed at the veteran sportbike pilot who has grown tired of crouching over clip-ons and rearsets, and helping to finance his chiropractor’s luxurious lifestyle though regular visits.

Pick a winner? Not a chance. Two bikes: two winners! You could call that a cop-out. We call it being spoiled for choice.

Off The Record

**Joe Neric **

AGE: 36 HEIGHT: 5'9"

WEIGHT: 230 lbs. INSEAM: 30 in.

Why don’t Americans buy standard-style motorcycles? These “naked bikes” offer performance and comfort. Sportbikes are a hoot for a half-hour, but I’m 20 years away from a cruiser. Who am I kidding? I’ll never buy a cruiser! A Gold Wing maybe—when I’m 60.

Both of these motorcycles are incredible, but I’m favoring the Honda, simply because it’s more fun to ride. Sure, the Kawasaki has more poke, but you’ll never notice because the buzz beneath your man-berries is so unbearable, it forces you to shift halfway to redline!

Just look at the CB1000R: What a sexy bike! Single-sided swingarm and futuristic design place this bike on my “Top 10 Coolest Bikes” list. Get it going, and it shines even more. It loves to be flicked into corners and is one of the easiest literbikes to ride.

Off The Record

**Brian Catterson **

AGE: 50 HEIGHT: 6'1"

WEIGHT: 215 lbs. INSEAM: 34 in.

If I had to choose between these two naked bikes, I’d pick neither. Give me a Kawasaki Ninja 1000, Motorcyclist’s 2011 Motorcycle of the Year, which for a few hundred dollars more would give me commodious wind protection and a passenger seat big enough to actually accommodate a passenger. The pillions on both the CB1000R and the Z1000 are so small, only a size-zero supermodel can fit. Which on second thought may not be all bad…

If you told me I had to choose between these two naked bikes, I’d choose the Kawi. Never mind that I’ve got one for a long-term testbike; its more powerful engine simply makes it more exciting to ride. With or without a supermodel on back.

2011 Honda CB1000R | Price $10,999

Ergos

Though the Honda boasts more legroom than the Kawasaki, a longer reach to its lower bars makes for a sportier riding position. Wind protection from that glorified headlight shell is non-existent.

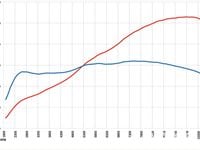

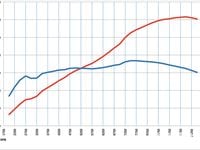

Dyno

A smooth horsepower trace and a plateau-like torque curve help make up for what the CB1000R lacks in sheer output. The fact that it's a couple pounds lighter with an empty gas tank helps little.

Tech Spec

2011 Kawasaki Z1000 | Price $10,599

Ergos

A shorter reach to higher bars makes the Kawasaki marginally more comfortable than the Honda. Vestigial windscreen works farily well, and provides a mounting point for aftermarket alternatives.

Dyno

With 17 more bhp and 10 more lb.-ft. of torque, the Z1000 makes any power comparison no contest. Little surprise, then, that it's a half-second quicker in the quarter-mile, too.

Tech Spec

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FZXHNOQRNVA3BIDWAF46TSX6I4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JRSFLB2645FVNOQAZCKC5LNJY4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ITNLTIU5QZARHO733XP4EBTNVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)