A nine-second quarter mile is approximately as relevant to most motorcyclists as Dario Franchitti’s 222-mph Indy 500 lap is to the average Honda Insight driver. But judging from most comparisons between Suzuki’s Hayabusa and Kawasaki’s Ninja ZX-14R, you might wonder whether either bike can even travel more than .25 miles at a time in a headlong rush of undistilled acceleration.

When the latest versions of the Godzilla-like ‘Busa and Kawi’s King Kong Ninja appeared in our own staging lanes, we wanted to do something different. Their dragstrip dominance is already well documented—for the record, the Ninja’s 9.69-second elapsed time fairly crushes the 9.89-second Suzuki, along with every other production bike. Fine, point made. Let’s move on.

We wondered instead how these big bruisers performed beyond the burnout box. With less-committed ergonomics than a traditional sportbike and more luxurious accommodations, we’ve always found both surprisingly adept at eating miles. And with less weight, more aggressive chassis geometry and substantially more horsepower than most touring sleds, both are still big fun on twisty roads. Could they turn out to be the ultimate compromise?

With hundreds of miles of California’s best back roads separating our El Segundo office suite from a mandatory staff appearance at Laguna Seca’s U.S. Grand Prix, all signs pointed to an impromptu sport-touring comparison. Ugh, we know, sport-touring… Just like SUVs, organic vegetables and microbrewed beer, the concept of sport-touring has been so co-opted and commodified that it’s largely become worthless. The first half of that hyphenate used to mean something, back when ST machines were essentially pure sportbikes fitted with taller bars, a bigger saddle and screen and maybe optional hard bags—not the bloated, barn door-faired mini-Gold Wings that define that genre today.

A multi-day, 1300-mile hyperbike tour presented the perfect opportunity to reexamine our understanding of what sport-touring should be. Call it sportier-touring, or speed-touring, perhaps. The Hayabusa and ZX-14R were obvious choices. Suzuki and Kawasaki have been singing a two-bar call-and-response with these models for over a decade now, and with this year’s release of the powered-up, traction control-equipped ZX-14R, the fight was fiercer than ever. Because this test would have a touring focus, we also added BMW’s K 1300 S, which blends tendon-stretching straight line performance with the long-haul aptitude of BMW’s traditional touring machines, to be our benchmark.

Our adventure started with the traditional Escape from El Segundo blast up the commuter-choked 405. Lower, closer-set handlebars and the lack of integrated hard bags make lane splitting and other inter-urban activities less nerve-racking than on conventional sport-touring machines. By the time traffic thins near Castaic, we’ve made some ergonomic observations. All three are more comfortable than any conventional sportbike but the BMW is the best of the lot. It’s relatively high, upright handlebar, ample wind protection and firm, supportive saddle is comfortable for a full tank at a time, and adjustable rearsets—part of the $4700 HP option package our testbike was equipped with—put the footpegs right where you want them.

Kawasaki’s is the second-best seat in this house, with a moderate reach to the bars and plenty of legroom, though the position could be improved by moving the pegs back an inch. The biggest bother on the ZX-14R is still errant engine heat. Despite extensive cooling-system upgrades and reconfigured side fins that route hot air away, the big Ninja bakes your ankles. The Hayabusa has the most aggressive riding position, with the longest reach to the lowest bars and the tightest seat-to-peg measurement, but it’s still more comfortable than any GSX-R. One average-sized tester even called it “perfect for this class.”

Later that day, on an undisclosed road just brushing the southeastern border of Death Valley National Park, we finally get an opportunity to pull the trigger on these big-bore ground missiles. Forget the quarter-mile sprint—you haven’t ridden any of these bikes until you’ve held the throttle pinned WFO for five miles straight. Any literbike can twist your shorts in a stoplight dash; what’s so amazing about these bikes is how ungodly fast they continue to accelerate even as the speedometer climbs. Especially the new, long-stroke, higher-compression Kawasaki that seems to pull just as hard above 150 mph as it does at 50. And all are just stupid fast—you should remember that the Hayabusa held fastest-bike honors right up until the manufacturers entered into a “gentleman’s agreement” to limit speeds to 300 kph (186 mph) in the name of general sanity.

So, the future promised us jet packs. Those never arrived, but these three motorcycles are an acceptable substitute.

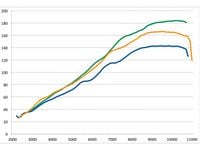

Horsepower is mostly a function of engine speed, and some 1000cc bikes—BMW’s S1000RR in particular—almost match the 183.9 bhp ZX-14R in terms of peak power. Where a liter bike can’t compete with these long-stroke, large-displacement mountain motors is torque. The K 1300 S delivers a steaming 87.2 lb.-ft.—16 more than the S1000RR—while the ZX-14R’s 108.9 lb.-ft. peak torque crushes everything short of Triumph’s 2300cc Rocket III. Besides shoulder-straining acceleration, such tremendous torque also provides a relaxed, luxurious ride character at low revs. These big-bore behemoths are barely breathing at 80 mph, turning less than 4000 rpm in 6th gear, with a hushed, unhurried fluidity that softens the hard edge off a long day in the saddle. And downshifting is unnecessary even when you need to get out of the way. All that torque acts like an automatic transmission, which you appreciate after 10 hours in the saddle, burning interstate to get home.

The ZX-14R makes more peak torque but the Hayabusa holds an advantage up to 4500 rpm, making the two bikes essentially equal in low-rpm roll-ons and off-the-line. If anything the ‘Busa is easier to launch, with a more predictable though stiffer clutch. The ZX-14R offers lighter action and smoother engagement but is more easily overwhelmed by engine torque, making a quick, wheelie-free launch more challenging. The K 1300 S is also strong off the bottom—70 percent of peak torque is online at 3000 rpm—but it’s slower to rev until 8000 rpm, where it really wakes up. The high-pitched wail from the HP-only Akrapovic exhaust only enhances the sensation of a pronounced top-end rush.

The BMW offers the cleanest throttle pickup and, aside from a hint of sogginess in the middle revs, excellent fueling manners. The Ninja’s K-TRIC injection programming is flawless and the Hayabusa’s SDTV digital throttle valve mapping is nearly as good, with just an off-idle stumble made more noticeable by driveline lash, the most of the trio. The Ninja’s gearbox is smooth and precise, save for an unseemly clunk when shifting back to first, a side effect of Kawasaki’s Positive Neutral Finder. The BMW is the best-shifting

bike here, because it’s (unfairly) equipped with an electronic Gear Shift Assistant (GSA) that enables instant, clutchless upshifts so you sound like Marco Melandri accelerating away from every stop sign. Note, too, that the K 1300 S is the only bike here with shaft-drive—lack of which is a deal-breaker for many hardcore touring riders—though you’d hardly know riding the bike, BMW’s well-developed Paralever system so effectively eliminates shaft jacking.

The Hayabusa engine employs a single balance shaft to counter vibration, so no surprise it’s buzzier at higher rpm. The ZX-14R and K 1300 S use dual counterbalancers to better effect, especially the Ninja. All three are relaxed at any reasonable speed—though the BMW is notably buzzier in the upper rev range—so you’ll often unwittingly ride miles on the freeway in fourth gear. Speed can be difficult to judge on such calm, composed bikes, and when just a fractional throttle turn translates to 20 mph, it’s not unusual to unknowingly exceed the posted legal limit—sometimes by lots. That was the case the next morning, on Highway 395 just north of Bishop, where a friendly CHP Sargent pinged us at 30-over. Luckily, our new EiC’s “highly experienced” hair coloring—and profligate name-dropping of Motor Officer friends at CHP HQ in nearby Sacramento—saved us the indignity of a staff trip to traffic school.

Our trip actually got worse instead of better. After our hour-long CHP conference, we noticed Mr. Ninja’s rear Metzeler had picked up a nail. Lucky that ex-Eagle Scout Cook had packed a plug kit, and after a quick stop at the Chevron in Mammoth Lakes for refreshments and compressed air, we climbed the High Sierras for a curvy counterpoint to the previous day’s wide-open, Death Valley test.

Highway 108—the Sonora Pass—is a twisted two-lane that climbs to 9624 feet at a 26-percent grade in spots, testing the handling of these ground-pounding beasts. Wheelbases ranging from 58.3 to 62.4 inches and curb weights all over 560 pounds make these sportbikes in the loosest sense of the term. With slow steering and pillowy suspensions that like to settle at the bottom of the stroke, both the Hayabusa and ZX-14R are clearly set-up to favor straight-line stability over quick-turning agility. Yesterday’s unshakable, 175-mph confidence is replaced with seat-munching fear, as both bikes plow past apex after apex, aiming straight for the nearest 300-foot drop—okay, that might be a slight exaggeration.

The Hayabusa has lighter, more neutral steering, while the Ninja demands a more forceful initial input and constant bar pressure to maintain lean angle. There’s no such thing as adjusting your line mid-corner on either bike—once you’re turned, you’re turned. Both Japanese bullets strongly resist turning in on the brakes. Their handling is more traditional: Get the braking done well before the apex, tippi-toe through, pound the throttle hard on the exit. Repeat as necessary.

The Hayabusa is firmly sprung and lightly damped compared to the Ninja, providing both more feedback and more unwanted chassis pitching. The plusher Ninja feels more put-together on rougher pavement, but it’s never entirely happy leaned over unless you’re seriously hard on the gas—it’s as though every chassis compromise was aimed at making the Kaw confident with all 180-some-horsepower leaning on that 190-wide rear tire. All it wants, really, is for you to be on the gas. All. The. Time.

Thanks to BMW’s Electronic Suspension Adjustment (ESA), the K-bike can be soft, sporty or somewhere in between. ESA alters spring preload and damping at the push of a button, with a Comfort setting for superslab duty, a Sport setting for canyon scratching and a Normal setting that splits the difference. The K 1300 S is equipped with BMW’s trailing-link Duolever fork, and its inherent anti-dive properties take some mental adjustment. Without front-end dive, the bike can feel vague, especially entering tight corners. Combined with relaxed geometry, the K 1300 S can feel more disconnected than it actually is, particularly during quick transitions or across off-camber sections. The K 1300 S is happiest on fast, flowing roads, where superior suspension action keeps the bike planted with a stability the other two struggle to match—even if the Sport setting is borderline too stiff for anything less than perfect pavement.

In addition to eSuspension, the K 1300 S is the only bike here with anti-lock brakes—ABS isn’t even an option from Suzuki or Kawasaki. BMW’s Semi-Integral ABS II engages all three Brembo binders with the lever to help keep the chassis settled (the foot pedal operates only the rear disc), and it offers plenty of stopping power but less-than-optimal feel—one staffer said the BMW’s brakes had “…more artifacts than the Smithsonian.” The system could engage more transparently, too—it would benefit greatly from sharing technology with the S1000RR’s excellent Race ABS. Kawasaki’s Nissin-made brakes are ultimately the best here despite lacking ABS, with loads of stopping power, progressive ramp-up and great, easy-to-modulate feel. Brakes are the Hayabusa’s weakest link, with lackluster power, wooden feel and a lack of progressivity that forces you to crush the lever to stop the bike hard. This is a major shortcoming especially on a curvy road, where the Heavy ‘Bus builds such unbelievable velocity between turns.

Day 3 brought us to Laguna Seca just in time to catch the first MotoGP practice session. Pulling into the parking paddock highlighted another advantage of these bikes over traditional sport-touring rigs: you’re still riding a quote-unquote sportbike, so you don’t feel like an outsider or Motor Officer imposter at the racetrack, or later that night on Cannery Row. For those of us teetering on the edge of midlife and still struggling with the concept of acting like an actual adult, avoiding the appearance of AARP membership is a critical concern.

After three fantastic days at the track alongside thousands of other like-minded moto-enthusiasts, highlighted by watching soon-to-be-retired Casey Stoner destroy the field in Sunday’s main event, we pointed our beaks southbound for the final component of this test: California’s legendary Highway 1. Unlike too-straight Death Valley or too-technical Sonora Pass, the Pacific Coast Highway south of Big Sur, with its seemingly endless succession of smooth, perfectly cambered, 50-to-90 mph sweepers, is perhaps the best of all possible roads to enjoy these uniquely capable long-haul sportbikes.

Successful sport-touring demands more than just outright performance; careful details, extra features and creature comforts become infinitely more important when you’re in the saddle for hours—or days—at a time. Here the Hayabusa comes up short. With a basic platform dating back to ’99 and no significant updates for the last four years, the ‘Busa shows its age. The styling looks tired and many of the details, like the black, molded-plastic cockpit surround, appear cheap. Extra features are virtually non-existent. The “trip computer” is decidedly last-century, consisting of just dual trip meters and a digital clock. Even the fuel gauge is old-school analog. The only electronic rider aid is Suzuki’s three-level S-DMS drive-mode selector that toggles between full power or two reduced-power maps. We’d much prefer a dynamic traction control system that actively manages the full power output to improve rideability.

The features-rich K 1300 S is the Hayabusa’s counterpoint. It’s got every gadget including traction control (called Anti-Spin Control) and two-level heated grips, in addition to the aforementioned ESA, ABS and GSA. The full-function digital dash displays average mpg, projected fuel range, ambient air temp and more useful data; a button on the left switch cluster allows you to scroll through the options easily. Moreover, BMW makes some really nice accessories for the K bike, including hard luggage. So many added features, plus the best ergonomics and wind protection, make the K 1300 S the best touring bike of the bunch—but such capability comes at a price.

The new-for-2012 ZX-14R offers traction control—mandatory equipment on bikes this powerful, as far as we’re concerned—in the form of Kawasaki’s excellent, switchable-on-the-fly K-TRC system, in addition to Full and Low power modes. KTRC is three-level adjustable and nearly undetectable in Mode 1, giving it an advantage over Beemer’s overly conservative ASC that kills all wheelies and cuts power noticeably out of corners. The Ninja also incorporates a full-function LCD trip computer that displays trip mileage, fuel range and consumption, voltage output and an adorable Eco icon that illuminates any time you’re riding in a conservation-friendly mode. There’s nothing more satisfying than throttling back and seeing the Eco icon light up at 160 mph…

The Hayabusa appears outdated alongside present company, but it’s still an amazingly capable machine. Ridden purposefully, it can still manage a credible GSX-R1000 imitation. It’s also the least expensive bike here and the one with the deepest aftermarket support, so it’s easy to optimize. In pure tire-kicking terms, however, the former king of the mountain is in desperate need of an update. The BMW is better equipped in every way and outcompetes the others in every area short of brute power and outright acceleration. It’s also considerably more expensive—even if you dial up the $15,555 base model instead of the $20,255 HP version seen here—and the Paralever/Duolever suspension combination is probably still a bit too eccentric for mainstream riders raised on conventional sportbikes.

Ultimately, the Ninja ZX-14R comes closest to the intended target. There’s no arguing about that engine, electric smooth and ungodly powerful. It’s wrapped in modern bodywork—though all of us found the electric-green-with-flames paint a bit garish—and a stiff, sophisticated, over-the-engine monocoque frame that provides a fine perch for piling up the miles. It also offers all the technology and features that we expect from a top-line bike in 2012—including traction control—for a competitive price. If you’re searching for a modern throwback to the good old days of sport-touring when the emphasis was squarely placed on eye-widening speed with a spice of sport, Kawasaki’s Ninja ZX-14R is the best bet.

AGE: 37 | HEIGHT: 5’7” WEIGHT: 155 lbs. | INSEAM: 32 in.

I was lucky enough to travel the Pacific Coast Highway between Monterey and LA twice this past summer, on very different bikes. The first time was with my daughter on a slug-slow Ural Gear-Up sidecar (story forthcoming), and I spent that trip dodging faster-moving RVs and Harleys. The second time was with this road-rocket trio, and I spent that trip worrying about the CHP pursuit plane! If Wide-Freakin’-Open is your preferred touring speed all three will get you there, but I enjoyed BMW’s K 1300 S HP the most. It’s the slowest bike here—very relative in this context—but the only one with a chassis that keeps composed down a twisty road, making it the easiest to ride fast. Once you stop worrying and learn to trust the feedback-free Duolever front end, that is. If it only had a sidecar attached…

AGE: 30 | HEIGHT: 5’7” WEIGHT: 135 lbs. | INSEAM: 30 in.

This was my first time riding big bikes over long distances, so I was a bit worried about this 1000-plus mile, high-speed adventure. These powerful beasts are surprisingly easy to ride—provided you don’t mindlessly whack open the throttle—but moving them around parking lots can be a challenge. The ZX-14R has a super-smooth engine with plenty of torque to power out of corners, even in higher gears. The pegs are too far forward, though, and the engine heat roasted my shins. The Hayabusa’s light steering made it easier to ride in the twisties, but the cheap plastic feel and difficult-to-read dash were turnoffs. Top-shelf fit and finish and all the fun HP extras made the BMW a fast favorite, despite the stiff throttle spring and hard seat.

AGE: 49 | HEIGHT: 5’ 9” WEIGHT: 190 lbs. | INSEAM: 32 in.

As we prepared to roll off on a 1300-mile comparison tour with the Laguna Seca round of MotoGP as the apex, I had second thoughts about bringing the BMW into the fold. I assumed it was just an outlier, an oddball bike that would be bludgeoned by the Suzuki’s smoothness and competence, and by the Kawasaki’s sheer brute power. Yes, it might be more comfortable, but it would get slaughtered on the road. Or so I thought. By the end of the tour, each of us was eager to switch onto the BMW. Its smooth engine, more upright ergonomics (including the best seat of the three, at least for me), fruity pipe and surprisingly useful quick shifter made up for the fact that it didn’t steer as nicely as the Hayabusa or pack the mind-altering acceleration of the ZX-14R. I don’t think I’d pop for the HP special edition, but the $15,555 base K 1300 S is, with the benefit of real road miles in the saddle, suddenly on my shopping list.

With the smallest engine here, it’s not surprising the BMW makes the least power. It still makes as much torque at 3500 rpm as the S1000RR literbike does at its 10,200-rpm torque peak, however, so acceleration remains frightfully fast. There’s just no replacement for displacement, though: the Hayabusa’s 101cc deficit to the ZX-14R translates into 23.5 less bhp and 9.9 fewer foot-pounds torque. Still, acceleration numbers are not far apart—credit that big bump below 4000 rpm on the ‘Busa map. But nothing else puts as much space under the curve as the ZX-14R, delivering face-melting acceleration in any gear and the quickest production-bike quarter-mile E.T. we’ve ever recorded. If you're looking for the fastest and quickest motorcycle made today, that search begins and ends at your Kawasaki dealer.

BMW K 1300 S HP: 142.9 hp @ 9500 Kawasaki ZX-14R Ninja: 183.9 hp @ 10,200 rpm Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa: 166.3 hp @ 9500 rpm

BMW K 1300 S HP: 87.2 lb.-ft. @ 6800 rpm Kawasaki ZX-14R Ninja: 108.9 lb.-ft. @ 7500 rpm Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa: 101.2 lb.-ft. @ 6900 rpm

BMW K 1300 S HP Price: $20,255

Kawasaki Ninja ZX-14R Price: $14,899

Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa Price: 13,999

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FZXHNOQRNVA3BIDWAF46TSX6I4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JRSFLB2645FVNOQAZCKC5LNJY4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ITNLTIU5QZARHO733XP4EBTNVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)