They say, “The CTX is your dream machine.”

We say, “If you dream of a low seat.”

For Honda, the watchword is “future.” Not necessarily referring to technology but, rather, to the necessity of filling the funnel with new riders. How do we get the fence-straddlers, or even those who never even considered a motorcycle, into the fold? How does the industry respond to a soft economy, where transportation expenses are scrutinized more thoroughly than a high-schooler’s report card?

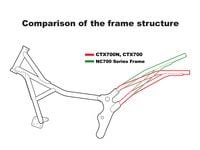

One answer was the NC700X, a super-tame, amazingly efficient machine based on clever but inexpensive technologies. Engine? A fuel-sipping parallel-twin with automotive roots and production efficiency as important as character or power output. Chassis? An adaptable steel-tube affair that rethinks packaging while also being easy to make and assemble. I keep saying “inexpensive” and “affordable” for a reason. Honda’s priced the CTXs aggressively. The base N (for naked) model runs $6999 with the faired version $7799. Add $1000 to either model and you get the automated-manual Dual Clutch Transmission and ABS. That’s a considerable difference from the original NC700X spec, which saw a $2000 disparity from manual to auto/ABS versions; Honda has since raised the base NC’s price by $500 and dropped DCT by the same amount. In theory, the more DCT machines it sells, the smaller the upcharge can be.

Why all the talk about the NC? Before now, Honda had three machines based on NC700 bones—our adventure-themed X plus a naked version and a scooter called Integra not sold in the U.S. Let’s add two more to the mix in the CTX, which Honda says stands for Comfort, Technology, and eXperience. Apparently the marketing department couldn’t find compelling reasons to promote X-rays, Xylophones, or, my favorite, the Los Angeles-based punk band X. (I can’t quite see Exene Cervenka or John Doe swinging a leg over the CTX, so it’s a moot point.)

Anyway, the basic CTX is a half-faired “light touring” model while an N-suffix version has a bikini fairing (do we even say that anymore?) and resembles a plastic naked bike cross-pollinated with a small cruiser.

Honda gathered the motorcycle press in swanky Westlake Village, CA, to launch the CTX. We had versions of both CTX and CTX-N models, though most were equipped with DCT. In fact, I didn’t get a chance to ride any of the bikes with a manual, but my own experience on the foot-shifted NC700X told me most of what I need to know. That is: The DCT is a fantastic mate to the 670cc parallel-twin’s demeanor, which strongly favors efficiency and low vibration over raw power or anything approaching animal magnetism. A 6500-rpm redline forces you to think about where you are in the powerband to anticipate shift points. But with the DCT, no problem; the computer does it all for you.

Honda has revised shifting strategies with this generation of DCT—compared to the original iteration in the 2010 VFR1200F—so the S (sport) mode is actually quite a lot of fun. It downshifts promptly, holds lower gears nicely, and runs the engine right to redline. D (drive) mode is pretty buzzkill; it wants to get to sixth gear as soon as possible, and is reluctant to kick down except with a handful of throttle. Of course, there’s a manual mode and two paddle switches on the left cluster if you want to DIY with the DCT, but you still have to mind the rev limit. In any of the modes, Honda’s latest DCT is well-mannered—fast shifts, very little clutch dithering on takeup or deceleration—despite a few clanks and clunks down below. Purists will want the foot shift, but the 30 percent of CTX buyers who Honda thinks will opt for DCT will be delighted.

Considering the CTX is so heavily based on the NC, you’d think it should feel similar. It doesn’t. And for that you can credit (or blame) the CTX’s cruiser-like riding position. I don’t get the feeling that Honda started out to build a plastic-flanked cruiser, but that the ergonomic layout was dictated by the laser-like focus on low seat height. At 28.3 inches, the CTX’s thickly padded saddle is 4.4 in. lower than the NC700X’s, and even 1.1 in. lower than a Shadow RS’s. That’s Harley-Davidson Sportster territory.

When you make the seat this low, the only option for your feet is to push them forward and down; a conventional sporty-standard location won’t work because you’ll be too cramped, and even a Sportster-like mid-mount location is far less than ideal. So it is that the CTX doesn’t look like a conventional cruiser, but it sits like one.

Honda’s efforts making the CTX feel low and light have paid off in the flesh, even though the bikes are actually a bit heavy. The company claims a curb weight of 478 pounds for the CTX-N and 494 lbs. for the CTX. Models with DCT and ABS weigh in at 500 lbs. and 516 lbs., respectively. All weights are with the 3.3-gallon fuel tank full. Yet because the bikes carry that heft low, they feel light coming off the sidestand and respond quickly to bar input once under way.

VERDICT 3.5 out of 5 stars

You'll meet the nicest people on what is probably the "nicest" Honda going.

Ergonomically, the CTXs are a mixed bag. The distance from the saddle to the pegs is generous, and the reach to the bar is about right—you don’t have to rise out of the seat to stretch at full lock, nor do the handgrips describe odd angles. But it’s a somewhat traditional cruiser layout, which puts a premium on seat quality and makes you a human sail, at least on the N model. The press ride was just 80 miles, broken up with photo stops and a scrumptious meal, so it’s hard to say if the saddle is all-day comfortable. I can say that the aerodynamics of the touring-biased CTX are very, very good. On a brief freeway stint, I felt no helmet buffeting and discovered that the laid-back riding position worked well in that generous still-air pocket. And, of course, the NC-based engine is so smooth and relaxed at highway speeds that it might as well be electric.

New and returning riders will feel like heroes at the first twisty road they encounter. Although Honda said that there’s “ample” cornering clearance, the pegs drag quite early. And that’s probably because the chassis is fine, with light(ish), predictable steering. While you’re still feeling quite good about the CTX’s cornering manners...sparks. This issue is probably not a deal-killer for the intended audience, but the chassis is good enough to take things further with a bit more daylight beneath the pegs.

The non-adjustable suspension has more travel than your typical cruiser's. At 4.2 in. up front and 4.3 in. at the back, the CTX’s suspension has enough travel to manage bumps large and small. Like the NC, the CTX is softly sprung but adequately damped, so while the chassis pitches moderately during aggressive riding, it doesn’t ever get out of hand. I don’t think I ever came out of the seat, despite our riding event including a few stretches of heaved-up pavement. Can't say that about the last Sportster I rode.

Bottom line on the CTX twins, then: Comfortable, docile, smooth, fuel efficient, and exactly right for Honda’s stated mission of encouraging new riders to join our ranks. But we can’t ignore the elephant in the room, and that’s the ill-fated DN-01. That scooter/speedster/sci-fi machine was, to be blunt, a dismal failure. Honda’s brass acknowledged this. “Remember that it was introduced in 2009, at one of the worst economic times,” said Honda’s Bill Savino at the press event. That, and the fact that the DN-01 cost $14,599, probably doomed it from the start. Its radical, what-the-heck-is-it? styling didn’t help.

What’s past may not be prologue largely because the CTX twins are much more conventional and a dramatically better value than the DN-01. Honda’s also gambling that riders coming into the sport in 2013 will see the CTXs for what they are—easy-to-ride, high-value machines.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)