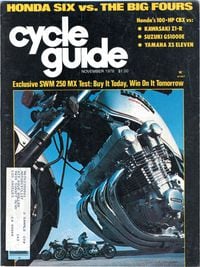

In the late 1970s, the pulse of Honda's streetbike lineup seemed alarmingly faint. It had been almost a decade since the launch of the mighty CB750 Four, arguably the most important machine motorcycling has ever seen. Since then, groundbreaking new motorcycles, previously a staple of the once-adventurous engineering company, had been in short supply. There were no Hondas winning comparison tests, no Hondas setting new performance standards, no Hondas causing bystanders' chins to polish their shoes as jaws dropped in amazement. Honda's magic lantern, it seemed, had gone dim.

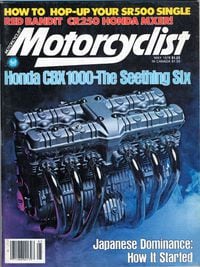

Then, in late '78, Honda's six-cylinder CBX burst onto the scene like a supernova. Just as such exploding stars can outshine entire galaxies, the brightness of the CBX's pedigree, its technical credentials and Honda's sheer chutzpah in building such a paean to excess threatened to shade the competition for a long time to come.

It wasn't the first time Honda had flexed its considerable engineering muscle to create such a powerful technological statement, nor would it be the last. The CBX, though, was one of the first examples of Honda building something thoroughly outrageous simply from the hardheaded desire to prove it could.

You might say the impulse sparked from a meeting in a motel room near Los Angeles International Airport in '76. That's how Cook Neilson explained it in his CBX road test in the February '78 issue of Cycle magazine. Honda R&D; personnel from Japan and the States had invited select U.S. motorcycle magazine writers to the meeting to ask what they thought about Honda motorcycles, and what Honda should do next. (Although commonplace at the time, such a thing—a motorcycle manufacturer asking the press what to build—has been absolutely unheard of for almost 25 years.)

The journalists told their hosts what they probably already knew: Although Honda motorcycles were solid, reliable machines, it seemed the excitement, the fire, the passion had gone out of them. To Honda, such a perception was simply not acceptable. Somethingsomething great and grand, a technological kayohad to be done. And so the CBX would be born.

Yet the CBX still would not have been possible—even conceivable—if certain elements were not in place, or about to be. To begin with, a six-cylinder street motorcycle had to be imaginable—someone had to come up with the idea. And that someone was Shoichiro Irimajiri, architect of several Honda roadracing machines from the '60s, including a brace of world-championship-winning six-cylinder engines, the 250cc RC-165 and the 297cc RC-174.

The career trajectory for new-hire engineers at Honda also conspired to make the CBX possible. Almost invariably graduates of Tokyo University, the young gearheads' first assignments were for Honda's race teams; baptism by fire, to be sure, but also the kind of challenge guaranteed to make a freshly schooled engineer twitch all over at the prospects. That's how Irimajiri got the enviable task of designing five- and six-cylinder four-stroke Honda GP engines to compete with the four-cylinder two-strokes of that era from Yamaha and Suzuki.

At the other end of the career arc, Honda engineers moved from racing projects to designing production vehicles for consumers. Saying "vehicles" is more appropriate than "motorcycles," because in the mid-'70s Honda was laying plans to become a major player in the auto industry. (And we now know how that played out.)

Up until '75, all of Honda's R&D; engineers (in Japan) worked in the same room at its research facility in Wako. In '75, though, Honda opened a separate motorcycle R&D; center in Asaka. That would be the new home for Irimajiri and like-minded engineers. And it was that environment which served as the genesis of the CBX—a brand-new R&D facility, staffed by engineers/designers of world championship-winning GP bikes, tasked to create a street-legal mass-production motorcycle that would leave enthusiasts and competitors alike stunned and gaping.

The stage was set, then, to create the quickest, fastest, most striking and extravagant thing on two wheels.Development of the CBX began in '76, and, perhaps reflecting the Six's appetite for speed, was completed in remarkably short time. Irimajiri, speaking in Cycle magazine's February '78 CBX test, said, "The CBX Six is a direct descendent of those [six-cylinder Grand Prix] race engines [from the '60s]. That's one reason it only took a year and a half [to develop the CBX]—we had the engine technology from our GP racing experience."

It's not uncommon for a manufacturer to do parallel development on a competing design, just to explore other possibilities, and that was the case with the CBX. A separate team also worked on a 1000cc inline four-cylinder, basically a street-going version of the DOHC 16-valve engine that powered Honda's '76 RCB1000 endurance racer. Not surprisingly, the six-cylinder engine pumped out 5 more horsepower: 103 hp (at the crankshaft) to the inline-four's 98 hp.

Yet Honda's decision to pursue the six-cylinder engine had almost nothing to do with its higher peak horsepower. In a letter to the International CBX Owners Association (ICOA) in August '90, Irimajiri said, "This [inline-four-powered] motorcycle was based on an endurance racer; and so it was extremely light, and actually much faster than the CBX. This fact became perfectly clear in comparisons on the test track; but nevertheless, we felt there was something exhilarating and exciting about the six-cylinder CBX that was lacking in the four-cylinder. The deep rumble of the exhaust, the feeling of acceleration, its smooth, high-revving enginesomething in the CBX that could not be measured in numbers such as speed and weight made it a very sexy machine.

"There was a big discussion among the project team about which motorcycle we should go with; and for our plan to develop a totally new superbike unlike any that had been made before, we chose...the CBX."

The team's conscious selection of the CBX over a design that offered measurably greater performance illustrated a curious departure for a company that had been most comfortable putting performance first. Fortunately, the same technology that won world championships for Honda in the '60s also helped make the CBX the quickest, fastest, most powerful production motorcycle in the land.

Yet despite its initial and rather narrow performance advantage over other liter-size motorcycles—along with a show-stopper of an engine that would not look out of place powering a Wurlitzer pipe organ—the CBX sold for only four short years. The first two years the CBX retained its standard/naked appearance, transforming into a sport-tourer for '81 and its '82 swan song.

With the aid of a little revisionist history, though, it's easy to see why the CBX lasted no longer than it did. Cycle's Neilson explains.

"I remember talking to some of [the Honda engineers] while Cycle was testing the CBX," Neilson says, "and they confided in me that—fundamentally, what they said was, 'You haven't seen anything yet.'

"What they were referring to was the V-four Interceptor, I think. Which, at that point, was clearly something they were working on. And they kind of suggested the CBX was a stopgap deal; a motorcycle they could build that would shock and amaze everybody, while they were working on stuff they knew was going to be more important." (Emphasis ours.)

All of which makes the CBX's story even more intriguing. It is remarkable enough that Honda spent untold amounts of time, money and effort to design, develop and produce an incredibly exotic street-legal production motorcycle. It practically beggars belief, though, that Honda did so as a makeshift measure. The engineers had to have known the Six was a dead-end design, especially when they already had a more conventional inline-four powerplant of greater performance waiting in the wings.

Still, Honda was jammed between a rock and a hard place. Bolstering a badly sagging reputation called forno, demandedthe most powerful statement possible, right now.

And it was that engine, the inline-six, that made everything possible. With the Six, Honda could utilize its heroic and hard-won GP history, shortening development/production time in the bargain. The CBX Six also demonstratedonce again, and with phenomenal claritythat Honda could build anything it could imagine. In the process, the CBX reestablished Honda both as motorcycling's unrivaled performance leader and its undisputed technological visionary. Conversely, it was the Six's weight and bulk disadvantages that condemned it to a short but intensely bright life.

Ultimately, it was the transverse inline-six powerplant, that quixotic expression of excess and engineering, that defined the CBX and, at the time, Honda. However briefly, the CBX was the brightest star in motorcycling's firmament.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)