More than 60 years have passed since the last of the original Indian Wrecking Crew turned a wheel in anger. One of its members, Ernie Beckman, has been gone for 18 years. The other two, Bill Tuman and Bobby Hill, still survive, both in their mid-90s, and continue to make special appearances at motorcycle gatherings from time to time. As recently as last summer, Tuman and Hill were special guests at Sturgis when Indian Motorcycle introduced its FTR750 flat-track racer.

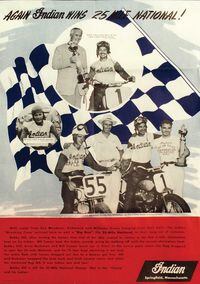

Tuman, Hill, and Beckman were known as the Indian Wrecking Crew back in the early 1950s. They were significant as the last of the factory riders for the original Indian Motorcycle, based out of Springfield, Massachusetts. It’s ironic that at the very time Indian, as a manufacturer, was failing and in its final days, the Wrecking Crew went on a tear. From 1950 to 1953, Beckman, Hill, and Tuman tallied an amazing 14 AMA National wins between them.

With Hill victorious at the winner-take-all national championship Springfield Mile in 1951 and '52 and Tuman in '53, Indian went out with a flourish, winning three-consecutive AMA national titles. Beckman's claim to fame was being the last rider to win a national on an Indian, when he earned victory at the 8-Mile AMA National Championship on the Williams Grove (Pennsylvania) Half-Mile in October of 1953. It would be nearly 64 years before the marque would again finish atop the podium, when Jared Mees rode the new-generation Indian Scout FTR750 to victory at the Daytona TT this past March.

Indian’s racing revival and the new company’s good-spirited efforts at paying tribute to the legacy of the original Indian means that Beckman and Hill have gotten more attention in the last year than they have since their racing days of the 1950s. “I think it’s wonderful that the new Indian remembered us,” Hill said. “It was a great feeling for Bill and me to go to Sturgis last year and see the appreciation we got from the riders and from all the fans. I’ve got to tell you, it’s tough just living day to day at my age, so those kinds of moments—to see that we haven’t been forgotten—well, it’s really something special.”

Motorcycle racing in the immediate postwar years was small and intimate. The racers were a close-knit fraternity. They traveled together, ate together, helped each other work on their bikes, celebrated one another’s victories, and generally got along well. Maybe the fact that most of the riders, including Hill and Beckman, had seen action in World War II, allowed them to put racing in perspective.

“We were grateful to have made it through the war,” Hill recalled. “And we all seemed to enjoy life, and racing was just as much about having fun and sharing time with your buddies as anything else. Don’t get me wrong—we all wanted to win, but you never got too upset even when things didn’t go your way.”

The Wrecking Crew trio all had unique personalities. Tuman—quiet, studious, and incredibly skilled as a machinist—was one of the guys the other racers went to when they needed help to get something right on their bike, and Tuman was more than willing to assist. So much so, that in 1950 he was awarded the prestigious AMA Most Popular Rider of the Year Award, as voted on by his peers. It was a huge honor in those days and showed the kind of respect Tuman had among the racing clan.

Hill was pleasant, friendly, chatty, quick to smile; you’d never guess he was a Marine. He was from a good family too. A black man they knew only as Willie, from Hill’s hometown of Triadelphia, West Virginia, was such a fan that he’d hop freight trains to go see Hill race in neighboring Ohio. This was the early 1950s and racing was still segregated and intermingling frowned upon by the clubs, but if Hill’s family was there to see Bobby race, they’d always give Willie a ride back home. Hill was known as a clean rider, one you could trust not to make an erratic move on the track. He was also a master of race strategy and had a reputation as a rider who was always on the hunt for the win as the laps wound down.

Beckman was brash, bold, and über-confident. His introduction to motorcycling was jacking an MP’s bike for a joy ride down the beach at Guadalcanal. One of the first races he went to he bragged to his racing buddy that he could go faster than the guys he’d been watching practice. His buddy called his bluff and offered Beckman his bike and racing gear to see if he was as good as he thought. Beckman gulped, grabbed his buddy’s gear, changed in a nearby horse barn, and suddenly found himself lined up to run his first motorcycle race.

The original Wrecking Crew was loyal to Indian even though they all three saw the writing on the wall—that the company probably wouldn’t be around much longer.

“It was different being a factory rider back then,” Tuman explained. “We’d get engines at the beginning of the season, and we were pretty much on our own from there.”

All three continued to race their Scouts for several years after the Springfield factory closed down in 1953. “We’d scrounge parts from old Indian dealers wherever we’d go to keep ’em going,” Hill said with a smile. “We knew what we were looking for, and all the dealers were real good about letting us have whatever we needed to keep the Indians on the track.”

The talent and winning legacy of the Indian Wrecking Crew meant that Indian went out with a bang instead of a whimper. It meant that the racing heritage of the company meant something for decades to come, almost to the point of being mythical. Quite possibly, it even inspired leadership of the new Indian to revive the legacy Beckman, Hill, and Tuman left us with more than 60 years ago.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)