Two weeks ago we published Part 1 of this 'behind the scenes' series on Bruce Brown's legendary moto-documentary On Any Sunday. Here's Part II, which has been every bit as much fun to put together. Enjoy.

Every time I watch the opening scenes of On Any Sunday, with Mert Lawwill walking down the street in a suit (really?), opening the back door of his van and then seeing – and hearing – him pitch his Harley-Davidson KR750 into a mile-race left-hander at 85 mph, it's goosebump- and hair-raising. Every time. It's also and a prime reason the movie is so immediately compelling.

Dirttrack racing is obviously a big part of the movie, with the footage of Mert and his competition coming from miles, half-miles and TT races from all over the U.S. Bruce and Mert would travel together in Mert’s van, while the film crew would fly to meet them at the events. Bruce and Mert both figured Mert would probably keep the Number One plate that year, but a string of mechanical problems cost him the points he needed to keep the title. Still, the footage gathered is simply amazing, with Bruce using to great effect a cumbersome and heavy movie camera fitted to several riders’ helmets to get some of it.

As we know, four riders were in contention for the National Championship at the last race of the season at Sacramento – Gene Romero, Dave Aldana, Jim Rice and Dick Mann. Romero, who seemed to have unbeatable speed that day, won the main event and grabbed the title in spectacular fashion, with announcer Roxy Rockwood's golden voice resonating in the background. Ironically, Romero and Malcolm Smith had battled each other a lot a few years earlier on Ascot's TT course, with Romero winning one month, Malcolm winning the next. The following year both were required to move up a class; Romero stayed with it, with Malcolm, who was busy running his new business at the time, quitting Class C racing for good and concentrating more on desert and cross-country competition.

Speaking of Malcolm and off-road racing, he and Bruce traveled together to the 1970 ISDT in El Escorial, Spain – Malcolm's fourth ISDT. There was no camera crew; just Bruce's simple, hand-held camera. Their routine was a bit different there. After lunch everything closed for a two- or 3-hour siesta; no restaurants were open, or any other businesses, for that matter. The Spaniards don't eat until 10:00 pm, so after Malcolm finished riding in the late afternoon, he and Bruce would head to the hotel, sleep for a while and wake up at 9 or 10 for dinner. Afterwards, it was time for bed and the eventual buzzing of the alarm clock at 6:00 the following morning.

Each night Bruce would tell Malcolm about all the good spots he had found to shoot. One evening, Malcolm remembers, Bruce was extra excited: “Bruce told me about a shot he’d gotten of a local Spaniard eating grapes while watching the race,” Malcolm told me. “That shot made the movie! Bruce had such a great sense of humor; we had a great time together.”

Shooting the ending sequence of the movie was a lot of fun for Malcolm, Steve McQueen, Mert and the crew. The scenes are amazingly emotional – riding with your friends, cow trailing, beach riding, sliding around, goofing off. It really does capture the essence of the fun of motorcycling, and Bruce did a masterful job recording it for eternity. The slow-motion stuff on the beach, the pranks, the music… It all brings the feelings of riding to life.

One of the three locations for the ending scenes was Bruce’s ranch in the hills above the Camp Pendleton Marine base just north of San Diego. Bruce had 700 or so acres up there, and had ridden there plenty, the Pendleton folks chasing him off the base property on many occasions when he’d venture too far across the property line. Anyway, on the way to the ranch to film those final scenes, Bruce asked Malcolm if motorcycle guys played tricks on each other. Malcolm told him of a couple pranks he knew of, one of which was spinning your rear tire on a soft cow pie so the yucky spray would hit your buddy riding behind you. Another was a water-crossing trick; let your unassuming buddy ride ahead slowly through the water, and at the last minute blast past and soak ’em thoroughly.

Bruce set Steve up to do the cow pie trick on Mert and Malcolm, and it worked perfectly. Being ultra competitive, Steve always wanted to be in front, and Mert and Malcolm were happy to let him go. He pulled ahead, aimed directly at the cow muffin with the throttle pegged, flicked the bike to his left and splat! The shots of Mert flinging cow poo off his arm, of Malcolm laughing, and of Steve looking back at everyone with an evil grin, are epic.

Mert and Malcolm got Steve back on the water-crossing scene, which Steve wasn’t ready for the first time they did it. He was under the impression they’d all ride through slowly, but of course Mert and Malcolm (and Bruce) had other ideas. They blasted him good, and Bruce, with a camera in the bushes, got the shot. They did more versions of it, and Steve got really wet and cold, but Bruce ended up using that first take, which was easily the best of the bunch. Watch the scene closely; just after Steve spits the water out of his mouth, he turns and you can begin to see the beginnings of a grudging smile on his face. “He knew he’d been had,” remembers Malcolm, “and good!”

Maybe the craziest thing that happened at the Ranch occurred months after the guys wrapped shooting. They were up there riding, the four of them, working on conquering the many hillclimbs there. These were actually on the Marine base, but the shelling and tank exercises never reached that far. Anyway, they came around a corner in an oak forest one day and ran smack into the midst of a platoon of Marines in camouflage, complete with tanks, guns and other weapons. “Their camouflage was so effective we couldn’t see them until we were in smack the middle of it all,” says Malcolm. “Riding here was almost a capital offense, and we were spooked. As soon as Bruce realized what was happening, he stopped his motorcycle, asked one of the marines who the commanding officer was, walked over to the guy in charge and said, ‘General Brown here. I hope things are going well. Carry on.’ The guy saluted, we started the motorcycles, and rode away. Amazing!”

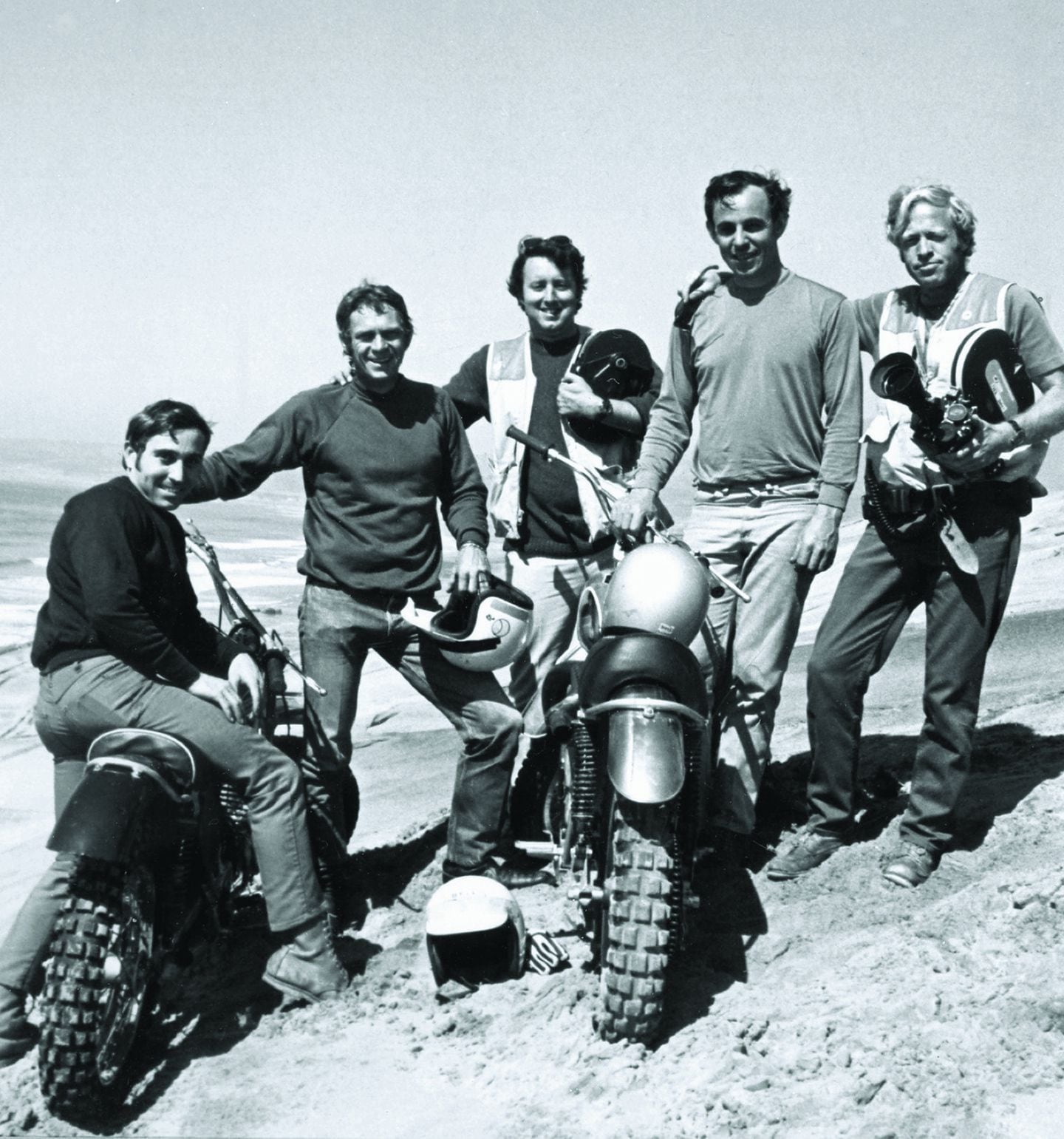

The sand dune footage was shot in Baja, Mexico, on the Cantamar sand dunes overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Steve, Mert and Malcolm basically ripped around the dunes while Bruce and crew filmed. Mert was riding a Greeves, but had put a Harley Davidson badge on it to keep his sponsor happy. Bruce didn’t have any fixed program for the guys; they were just ripping around, carving up the sand, and having a great time while Bruce and company filmed. Once, Mert and Malcolm narrowly missed a head-on collision coming over opposite sides of the same sand dune. “There were some wild crashes that day,” Malcolm remembers. “One was Steve looping over on a dune jump; he hit the ground pretty hard, right on his butt, but bounced up quickly, faking a heart attack and falling to the ground! Mert fell hard, too, highsiding after landing from a jump, his hip smacking the engine case and front wheel.”

For the last day of filming, Bruce wanted unstructured riding for fun on the beach at Camp Pendleton. He called the base commander for permission and explained what he wanted to do. The commander’s reply was succinct: “No way! No how!” Bruce told Steve about the call, and Steve asked Bruce for the commander’s phone number. Steve called, introduced himself, told the commander about the motorcycle movie he was filming, and asked again to use the beach for the day. The commander said, “OK, Mr. McQueen, anything you want! What do you need? Can we send some Marines to help?”

The closing scenes of the movie are wonderfully captured, the kitchy, ’60s-era soundtrack music making it all superbly memorable. According to Malcolm, the riding was insanely fun, especially the shots of the guys power-sliding on the moist sand during low tide. “That sort of moist sand is usually glass smooth,” Malcolm says, “with lots of consistent traction. I love doing big medium-speed doughnuts in the sand. With the throttle on, it’s a power slide. Crashing on the low side isn’t too bad. But if you chop the throttle too much you get highsided, which can hurt. Steve did it several times that afternoon.”

According to Malcolm, Steve was always very competitive and worked very hard at leading whenever we rode together, but he crashed a lot during those three days of filming the play riding. “At the end of the third day we all jumped into Bruce’s hot tub,” Malcolm says. “Steve was a mess; what wasn’t black and blue was skinned up, or both! Still, Steve was a very competent rider and loved motorcycles.

“You expect movie stars to be magnets,” Malcolm says, “but Steve was in another league. People – women especially – noticed him everywhere he went, but he was usually quite good about the attention and autograph seeking unless they were rude or inconsiderate. He also had a helluva sense of humor. I remember riding with him to Mexico in his hopped-up Ford pickup to do the sand dune filming at the end of the movie. At a border toll booth he just blasted through, knowing that Bruce – who was right behind us – would pay for both of us. He was a very funny guy at times.”

After the guys wrapped shooting, Bruce began the narration and editing process. It took him about nine months to finish editing On Any Sunday, working twelve hours a day, six days a week, all with help from cameramen Don Shoemaker. Even at that point, Malcolm figured he'd have only a small part in the movie.

The first showing was at a theater in Westwood, California, very close to the UCLA campus and just a few miles from Beverly Hills. Admission was only a buck, but there was a catch: Moviegoers had to review the movie verbally with Bruce after the showing. It was Bruce’s way of gauging reaction, and seeing what did and didn’t work. These were regular movie-going folks, not motorcyclists, which was probably good and bad. Folks generally liked the movie, but felt it was a bit too long. The least-liked part was the Speedway section, which Bruce eventually cut from the final version.

“I had no clue until that point that I would be featured so much,” remembers Malcolm, “and I was thoroughly surprised. A year had gone by since we’d finished shooting, and the movie had faded from my radar screen with everything I had going on. But it was amazing. Bruce had done a masterful job. His sense of timing, humor and wording added a highly personal dimension to the many stories in the film. I often wonder how things would have turned out for me had I not been in the film. But what’s clear is that Bruce gave me millions of dollars of free publicity, and the movie today is more popular than ever. We sell copies of the DVD like crazy from our store to this very day.”

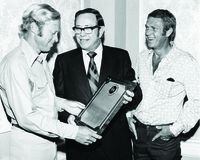

Nominated for an Oscar (best documentary), On Any Sunday was narrowly edged out by the Hellstrom Chronicle – a movie few remember today. Not long after the film's release, movie moguls from the big studios came knocking on Bruce's door. One group had him come to their Hollywood studio so they could talk him into working for them. They offered him a $1 million salary, which was a lot of money in 1972, plus a percentage of profit on films he did. They'd already painted "Bruce Brown – Director" – on the door to his new office, which was manned by an especially pretty secretary. After they finished their pitch, Bruce gave them his take: "Thank you, but no. The only boss I've ever had or wanted is me." And he walked away.

In the early 1980s, according to Malcolm, some shuck 'n jive guys bought the rights to make a sequel to On Any Sunday. Bruce wasn't involved at all, having pretty much retired after OAS I. "They rounded up investors," Malcolm says, "then came to see me one day in a big black Cadillac limousine, with two hot babes inside. They got me into the limo and tried to persuade me to invest. I felt they weren't honest, and didn't give them a penny. Anyway, the project stalled and had to be rescued by Joe Parkhurst of Cycle World and Roger Riddell. But without Bruce's talent, it flopped."

Luckily, we are left with the epic original.

"All in all," says Malcolm, "it was an amazing project to be involved with. I never, ever could have imagined the positive effects it would have on me in the coming years."

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/42A3WEFRONPZTS75S5UES2PP7Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)