On Any Sunday. It never fails to raise whoop-sized goosebumps on my arms and neck. Never.

Every time I watch it – and I do about once a month, from beginning to end, which is exactly one hour, twenty-eight minutes and 39 seconds – it happens: I lose track of time; I become instantly engrossed; I flash back to those wonderful days as a kid on my Honda SL70 in the early '70s in rural Ohio; I marvel at how freaking impactful and significant it has been in the years since its release – which, in 2016, numbered forty-five; and I'm reminded once again of how grinningly, droolingly wonderful motorcycling really is.

By the time I began sitting down with Malcolm Smith on a weekly basis in 2012 for the autobiography he and I published last year called Malcolm! The Autobiography (www.malcolmsmith.com or www.themalcolmbook.com), I'd already watched On Any Sunday dozens of times. But as we dug into Malcolm's life, and spent quite a bit of time talking about his involvement with the movie and his good friend Bruce Brown for Chapter Six, I got to hear a lot of the background and inside information about the movie … about Mert Lawwill and Steve McQueen, what happened when the cameras were off, and how it all came together over that crazy year of filming. Every bit of it was fascinating.

Those of you who’ve already read the book will be familiar with some of this. But for the many thousands of enthusiasts who haven’t yet gotten the book (it makes a great Christmas present for yourself or a friend), I figured they’d appreciate a look behind the scenes into our sport’s most lovable and enduring motion picture.

The best place to start, I guess, is at the beginning: how the movie came to be, and how Malcolm came very close to not being involved in it. Amazing to consider, I know…

Bruce was a So Cal surf guy, and after releasing his epic The Endless Summer surf movie in '66 he'd slowly drifted into the motorcycle scene, going to races at Ascot Park and out in the desert, and eventually buying a bike from – you guessed it – Malcolm Smith. Over time, Bruce realized how well-rounded Malcolm was as a racer and rider, and as his idea to do a moto-documentary began to gel, he saw Malcolm as a key part of the puzzle.

To finance the film, Bruce approached megastar Steve McQueen, who he didn't know, and who, naturally, figured Bruce wanted him to star in it. When Bruce told Steve he only wanted McQueen to finance the film during their initial meeting, Steve said he acted in movies, not financed them. Fine, Bruce told him good-naturedly, then you can't be in the film! Steve called back the next day, and told Bruce to get going on the project.

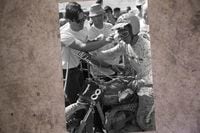

Malcolm was a harder sell. When Bruce asked Malcolm if he wanted to be in the movie, he said no despite wanting very much to be involved. Malcolm had just purchased K&N Yamaha (where he’d worked for several years) from Kenny Johnson and Norm McDonald (who were then launching K&N Air Filters), and was underwater trying to manage the new enterprise; Malcolm simply felt he couldn’t spare the time with so many business headaches. Luckily, Bruce asked again a couple of weeks later, and, having straightened a few things out at work, Malcolm said yes…especially once Bruce offered to pay Malcolm $100 for every day he was out of the office! Given the exposure the movie has given Malcolm over the years, it was one of the better decisions he made.

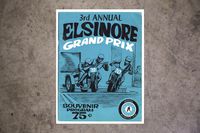

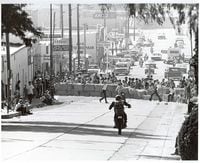

One of the first events Bruce filmed was the Elsinore Grand Prix, a race held annually in the town of Elsinore, California, some 70 miles southeast of Los Angeles. The race began and ended near the town center, on the asphalt, and ranged out in a 10-mile lap over dirt fire roads and sand washes. 250s and under raced on Saturday, with the open-class bikes competing on Sunday. Elsinore attracted some 1500 riders from all over the country back then, and as Bruce says in the film, “If there’s one event you ride each year, it’s the Elsinore Grand Prix. People of all ages… Girls, the pig farmer from Murietta.” It was a real happening.

There had been lots of rain in the days leading up to the race, and in one section there was a giant puddle – which quickly turned into a mud bog during the first lap. By the time the last riders got going, there were tons of bikes bogged down in the axle-deep mud, stuck between the barbed-wire fencing. The mudhole would become a topic of great controversy in the outcome of the race, and it involved Malcolm directly.

Malcolm got away quickly and was soon leading, feeling really comfortable on Elsinore’s dirt roads and sand washes, and soon had a decent-sized lead over the second-place rider as he came into town at the end of the first lap. As he approached the mud hole on lap two, he could see quite a few stuck and abandoned motorcycles. “I skirted the edge of the hole next to the fence where the dirt was a bit firmer,” Malcolm remembers, “but still had a moment or two as I ripped through there pinned in second gear, at times using the sunken wheels of fallen motorcycles for traction. But I made it. I remember seeing officials cutting the barbed wire as I did so, presumably to route riders around the hole onto dry ground for the race’s later laps.”

For many competitors, the mud hole was the end of their race. Just about everyone was muddy from the slop, too, the goo obscuring number plates, which caused scorers to miss many of the numbers. This made it seem as if some riders didn’t complete all the laps, and certainly added fuel to the brewing scoring controversy.

When Bruce edited the film, he showed Malcolm going through the barbed wire and around the mud on dry ground, which gave the impression that he'd cut the course. Of course, by that time, the course had been officially rerouted outside the fence, and what was shown in the movie was actually his third lap, not his second. A close look at that footage shows the mud hole basically empty, which it was not on his second lap through.

The logistics of keeping track of more than 1,500 riders, many with muddy and obscured number plates, wasn’t easy, though it would be many days before everyone knew just how screwed up things had gotten. As stated in the Elsinore Grand Prix brochure, “There will be no results of any type during the two-day event. Results will be announced at the Newporter Inn in Newport Beach on Friday night, the 13th of March.” The two-week interval between race day and the awards night dinner would allow organizers to sort through and organize all the data they collected on the race, which included a video and real-time lists by scorers who checked off rider numbers as they passed an intentionally slow and narrow portion of the course specifically designed to make the scorers’ job a little easier. Unfortunately, the video tape used for the Saturday race was overwritten when the video of the Sunday event was done. Real-time scorers showed missing laps for a number of riders because of mud on their number plates, and there was no longer a method for reviewing and confirming the race.

The announcement of results in Newport Beach a couple of weeks later showed Malcolm 6 minutes ahead of second-place finisher Gary Bailey in total time, but missing a lap, therefore removing him from the top finishers. The organizers reviewed their information several times after the initial announcement, especially after hearing the outcry about Malcolm not having officially won. But despite a wide consensus by all involved that he’d won by a wide margin, they never changed their official position. Bruce, of course, got it right in the movie.

Malcolm's friends were miffed about the screw-up, and took out a full-page ad in Cycle News a week or two later in protest. The ad read: Hey World! Malcolm Smith won Elsinore! Riders know it! What's your problem, Gripsters? -Signed, a rider and truth lover!

The Gripsters, of course, were the sanctioning body, and the ad was a good-natured poke at their less-than-efficient scoring abilities. Malcolm wasn’t too worried about the official results. Everyone knew he’d won.

Sunday’s open-class race would be far more problematic for Mr. Smith. Malcolm rode a Husky 360 that day, which was 10-20 mph faster in top gear than most of the other bikes. Malcolm was again able to lead the pack into town, and by the end of the second lap had begun to lap some of the other riders. As we all know from watching the movie, spectators often ran across the roads during the races, and this caused a big problem for Malcolm. As he ripped into town on the second lap he was quickly catching up to a group of lapped riders. Seeing the group of soon-to-be lappers go by, a lady with two small children stepped off the curb into the street, thinking the lappers were the only traffic around. She didn’t realize Malcolm was bearing down on her at about 80 mph, probably 20 mph faster than the lappers.

“I found myself headed straight for the smallest child,” Malcolm says. “I swerved, and the handlebar went over the child’s head, but it struck the mother in the chest, tossing her violently into the crowd, and fracturing several ribs in the process. The maneuver flipped me over the high side, and I tumbled down the pavement. I was skinned and bruised, and thoroughly upset. I kept flashing back to how close I had come to hitting a child. I was so shaken, all I could think of after I got up was going home.” Luckily, the woman recovered, though she later tried, unsuccessfully, to sue the organizers of the race, the city of Elsinore, and Malcolm, too.

One of the more memorable scenes in the movie was the poor guy stuck out in the desert after a desert race, sitting forlornly on his Husky, waiting for help. That guy, according to Malcolm, was John Creed, who ended up running the Chart House restaurant chain. According to Malcolm, Bruce came up with the Husky/fire idea, and Malcolm had the perfect bike for it – a repossessed Husky with a blown connecting rod hanging out of the bottom of the engine.

The comedic and obviously staged scene, which shows the lost rider using the Husky’s fuel to light a signal fire, ends with the bike catching fire. The fire was real, and most folks probably think the bike in question was a total loss. Not true. Malcolm repainted the tank, replaced the cables, rebuilt the engine, used new tires and seat, and ended up selling it at some point. “I often wonder who has that bike now,” he says, “though I doubt there’d ever be any way to confirm its history. But it’s out there somewhere, I’m sure.”

One weekend Bruce and Malcolm flew to the Widowmaker hillclimb in Utah, just south of Salt Lake City. Bruce’s cameraman brought Malcolm’s stock Husky 400 in the truck. The Widowmaker was so steep that no one had ever climbed it on a bike.

Malcolm was riding a stock Husky, and on his very first run he ran out of gas after forgetting to turn on the gas. “I really did forget,” he told me! “On the next two runs I made it up the hill farther than any of the other stock bikes. Coming back down, the other riders were getting off and bulldogging down the hill, usually with the help of two or three spectators. I just turned around and rode it down, just like I had always done when play riding.” That year was also the first time someone had actually made it over the top – Mike Gibbon from Grants Pass, Oregon, who rode a modified 750 Triumph hillclimber with chains on the tire and nitro methane fuel in the tank. In later years, after the hill became too easy for the newer bikes, a much steeper, longer, curvier and rougher climb was made on the same ridge; and that one was finally conquered on bikes similar to the specially built Team Peterson KTM bikes Malcolm sponsors today. The hill lies right next to Interstate 15 on the southern end of the Salt Lake valley, and if you look closely today you can still see the hillclimb lines cut during those two decades of racing, though expensive homes are now built up against it. “I didn’t have a lot of time to enjoy my Widowmaker adventure,” Malcolm told me. “I came up the night before, and came back the evening of the next day. Hey, I had to work!”

There are many more inside stories surrounding Bruce Brown’s epic movie, so stay tuned for Part II in the coming weeks. Meanwhile, I’ll just finish watching the movie’s epic ending scenes, shot on the beach at the Marine base at Camp Pendleton…

"On Any Sunday, I'm a flying maaaannn…….." Gotta love that music.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YRYUMZND2V2KJCVYFLG6YTLYDM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)