The bike debuted at the Tokyo Motor Show in October of 1970. There the GT750 prototype sat, sparkling in its Candy Lavender paint and impressing everyone with its sexy styling and liquid-cooled 750cc triple. Suzuki’s then-current production streetbikes—the 250cc X6/T250 and 500cc T500—were competent yet stodgy, but no one was using those words to describe the GT750 prototype.

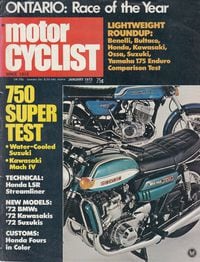

A hit of the show, the GT750 was described by Cycle World as "one of the eye-poppingist machines to be seen in a long time." England's Motor Cycle said: "Suzuki have stepped into the big league with what must be the most complex super sporting roadster ever built. As sales of its 500cc twin suffer from the popularity of Kawasaki's 500cc triple, it seems probable that this 750 may help restore Suzuki fortunes in the USA."

The idea of the GT750 being a sporting thrill ride made sense to enthusiasts. Here was a motorcycle powered by a 750cc triple built by a company with plenty of GP heritage. How could the GT not be an amazing sporting machine?

“Early speculation,” remembers US Suzuki manager Jim Kirkland, who was new to the company in ’71 and who works there to this day, “was that it would be a hot rod, an H1-beater. With water cooling, and the GP success Suzuki had had… Yeah, expectations were high for a real runner. We then heard from the Japan staff that the new 750 was not a hot rod but a more all-’rounder. We wanted an H1-beater, wanted a bike that would generate excitement.” Suzuki had been plenty conservative during the ’60s and early ’70s, and a younger faction at US Suzuki was clearly looking for more excitement.

“Suzuki was still a small, traditional company,” Kirkland says. “And those running things, here and in Japan, were older. Despite the desire for a hot rod, I felt they did not want to take the risks Kawasaki took. Kawasaki was much bigger and could afford to be risky. A friend of mine from Kawasaki told me they built crazy bikes like the H1 and H2 [the latter debuted the same year as the GT750] almost purely for the publicity. Looking back,” Kirkland adds, “the do-everything direction Suzuki took for the 750 and the entire GT lineup was surely the right one; it established Suzuki as a serious builder of really good all-around motorcycles.”

Most GT750 development happened in Japan, but there was some pre-production testing done in Southern California, Nevada, and Utah. “We did some long-distance testing,” Suzuki’s Willie Hardin recalls, “riding to Las Vegas and Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats. We brought a Triumph Trident, but for some reason they’d not gotten a CB750 to test alongside. Everyone expected the bike to perform like an H1 or H2, but it was clear they’d made the GT more of a sport-touring bike. The GT was heavy and didn’t handle particularly well, but it was comfortable and smooth and very torquey. There wasn’t much to do, really—just refine suspension and jetting. The bike was pretty complete by the time we rode it. Still, it wasn’t what most of us expected.”

Dealers and customers were excited as bikes began arriving in Suzuki shops in early ’72. Painted in a pair of bright colors—Candy Lavender and Candy Jackal Blue—the GT750 dominated showrooms aesthetically and openly displayed Suzuki’s engineering prowess. The quality and depth of the GT’s paint and chrome definitely impressed, but it was the bike’s finless, smooth-sided engine and prominent radiator that kept enthusiasts smiling, imagining big power.

“That first GT750 was definitely impressive,” a longtime Suzuki dealer remembers. “It was big, bold, and beautiful, and in our showroom it made everything look better. I remember thinking it was more Honda CB750 than H1 or H2 and that the hot-rod guys who loved the Kawasakis might not like it. But it was a very good motorcycle, and we ended up selling plenty.”

There were concerns about the bike’s lack of raw performance, especially from hard-core riders and the magazines, who pointed out the bike’s weight and less-than-stellar quarter-mile times, especially compared to the Kawasaki H2, also new in ’72. But it was functionally excellent: smooth, comfortable, and very, very refined, with easy handling and a surprisingly torquey, easy-to-use engine. “It was so different than the Kawasakis,” Kirkland says. “Despite some grumbling, it was generally well accepted by dealers and, soon enough, by owners.”

The magazines noted the GT750's lack of cornering clearance, its soft suspension, and its lack of a disc brake up front. (The bike in the photos has a Suzuki-supplied brake kit to replace the front drum.) But even the most narrow-minded scribe couldn't miss the many things it did well. "In most respects," wrote Cycle's editors, "the Suzuki's riding comfort is excellent… The saddle is soft, broad and comfortable. The GT750 rides pretty nicely… Its mass forces the tires to eat small irregularities on the road…"

Amazing engine smoothness helped. "Triples with 120-degree crankpins have fairly strong longitudinal rocking vibration," Cycle continued, "and the Suzuki is no exception. [But the] elastic engine mountings keep the vibration largely confined…rather than spreading them throughout the motorcycle. The water-cooled Suzuki is one of the smoothest motorcycles available anywhere."

Smooth, and torquey, too. "The GT750," Cycle said, "develops real muscle only within its power band…which begins at about 2,000 rpm and stays with you all the way to the 7,000-rpm redline. The machine as a whole may be slightly confused about its identity but the engine is perfect for touring. Torque is what the touring rider needs and torque is what the GT750 has in abundance."

The first-generation LeMans, as the GT750 was known in America, did have a few foibles. “Issues,” says noted GT750 expert Alex Rossborough, “included problems with unleaded fuel and weak condensers, keyway breakage and resulting timing issues, and cylinder assemblies chemically welding themselves to crankcases over time. Crank seals would dry up and leak, the discs on ’73 and later bikes need to be drilled, as they hydroplaned in wet weather, and stock chains were plenty weak.”

“The cool thing about the Water Buffalo,” says Suzuki’s Kirkland using the GT’s much-loved nickname, “is how long they last. People who had and have them really love ’em. And some rode the hell out of them—60, 70, 80, 90,000 miles. I saw the inside of one engine with nearly 100,000 miles, and it looked fresh and measured up really well, with minimal wear.”

“Would we have sold more if it’d been sportier?” Kirkland asks rhetorically. “Probably. The demographics were younger then, and motorcycling was a young man’s sport at the time, with a lot of buyers coming off dirt bikes. Kawasaki broke ground there, doing better with more sex appeal and performance. We tried to make the GT a bit faster in ’75, with port timing changes and CV carbs but got hate mail! The bike surged, and we had product service bulletins to combat the problems. But we sold of lot of ’em. Sales doubled every year, and everyone was happy.”

Cycle concluded: "The bike stands exactly equidistant between true superbikes and comfortable tourers. Only a nudge is needed to move it a long way in either direction."

The GT750 lasted six years, right through the 1977 model. It’s a bike that truly was before its time—but already out of date by its second year. The reason? Suzuki’s move to four strokes in the form of the 1976 GS750, development of which began in 1973—all precipitated by Kawasaki’s launch of the mighty Z-1 and the ever-more-stringent smog laws that would eventually choke off all two-stroke streetbikes. Suzuki saw the writing on the wall and wisely chose to move in a different direction—a direction that ended up bringing us the legendary GSs and GSX-Rs. But in the early and mid-1970s, the Water Buffalo burbled along happily, giving many thousands of motorcyclists a wonderfully capable, all-around ride.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)