When was the last time you were truly ambushed by extreme weather, despite knowing better? Perhaps you found yourself grappling with the wind, which persistently pushed your motorcycle across the road, unzipped your jacket, or caught your helmet in a fierce upward gust. Maybe you’ve felt the sting of rain or hail against your face, like a thousand icy needles, or heard the thunder chastise you, its booming voice echoing off canyon walls. And yet, through it all, your grin remains, wide and defiant. In that moment, you are vividly, undeniably alive, and perhaps, more inventive than ever.

The drive to survive has a remarkable way of unleashing the depths of human creativity and problem-solving capabilities. In moments of extreme adversity, our minds can tap into unconventional and innovative solutions that were previously hidden or overlooked. Seemingly unrelated ideas are streamlined, drawing upon our cache of diverse experiences and knowledge to devise innovative strategies. The pursuit of survival demands that we think beyond the box, using our imagination and inventiveness to overcome obstacles that stand in our way.

Perhaps that is why, as I rode my Royal Enfield amid the dense hailstorm enveloping Ecuador’s highest peak, I found myself pondering how the journeys of early explorers might have differed had they possessed a trusty motorcycle. Soaked to the bone and shivering, I imagined a world where the intrepid naturalists of the past straddled roaring motorcycles instead of trudging through the elements on foot and mule. How would their expeditions, painted with a more modern, adrenaline-fueled hue, have unfolded?

Twisting up the foothills of the Chimborazo volcano in Ecuador, I ascend closer to the altitudes beyond the treeline. Eucalyptus trees, with their shaggy bark and air of enchantment, flutter in my wild wake. The volatile oils of their leaves steep my lungs, invigorating my spirit like a sharp menthol elixir for the soul. My body tingles as these leafy sentinels stand guard along the pavement’s edge, watching over the lush green farms that extend through this dreamlike landscape.

This stunning backroad connecting Ambato and Guaranda is a journey not to be missed, featuring sweeping curves that trace the Rio Ambato toward the entrance of the Chimborazo reserve. Known locally as Vía Flores, this dynamic route zigzags over narrow bridges, repeatedly crossing the river before ascending the flanks of the massive, steep, and conical stratovolcano. It carries me closer than anywhere else on Earth to all things celestial.

Our planet is not a perfect sphere; it bulges slightly at the equator due to the centrifugal force exerted by Earth’s rotation. Chimborazo, Ecuador’s tallest mountain, stands at 20,702 feet (6,310 meters) along the equatorial line, making its summit the closest point on Earth’s surface to the sun, moon, and stars.

While I struggle with altitude, I’m grateful for fuel injection. Climbing higher, the scenery grows increasingly hostile. My vital organs plead for more oxygen, an ominous shadow of a headache looms, and my perceived place in this world shrinks into a fragile speck of existence. Snow lines the road, and my icy fingers struggle to pull in the clutch. Vicuñas, the wild ancestors of alpacas, trot over the curved horizon of the volcano, vanishing from sight. A white cloud blankets my vision. Then comes the hail, pummeling my helmet, ricocheting off like a lottery ball machine.

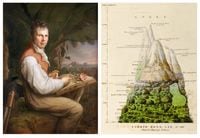

Enveloped in this harsh environment, feeling insignificant and vulnerable, I can’t help but recall Alexander von Humboldt, the renowned explorer who attempted to summit Chimborazo in 1802. His name is well known not only for his significant contributions to the natural sciences but also for the many geographical landmarks, scientific institutions, species, and other tributes named after him—such as the Humboldt Current, Humboldt Redwoods State Park, and the Humboldt penguin. Humboldt didn’t try to summit Chimborazo out of a desire to conquer a peak (despite holding the record for highest climbed ascent for 30 years), but as a curious naturalist who had a hunch that mountain ranges were the result of past volcanic eruptions.

To distract myself from my frigid feet, I wondered, “What if Alexander von Humboldt had a motorcycle?” Humboldt died in 1859, nearly three decades before the invention of the first gas-powered motorcycle. Ignoring chronological timelines for the sake of mental escape, I followed the thread, conjuring an image of the specific bike he’d ride. Being German, he’d probably ride something from his home country.

“My vote would be a vintage BMW R80 G/S, a proper adventurer’s motorcycle,” says Ben Branch, founder of Silodrome: Gasoline Culture.

The BMW R80 G/S, often considered the “World’s First Adventure Bike” was produced in Berlin from 1980 to 1987. As popular and highly regarded as this bike became, many are unaware that before the official release of the first BMW G/S, two prototypes were tested in Ecuador by BMW spokesperson Kall Hufstadt and journalist Hans-Peter Leicht. To assess the motorcycle’s performance in extreme altitudes, climates, and road conditions, they embarked on a successful 2,000-kilometer journey, inspired by the motto “from rainforest to endless ice.” Their route spanned from the tropical, humid Amazon basin, through the muddy cloud forests, and up to the low-oxygen, glacier-capped volcanoes of the Andes. Eight months later, BMW unveiled the first touring enduro.

- Humboldt would be traversing the same terrain, so the R80 G/S may be the perfect consideration as his steed for several reasons:

- Design: The R80 G/S was known for its distinctive design, with its long-travel suspension, rugged appearance, and protective fairing.

- Versatility: It was a capable off-road bike, but also offered a smooth and comfortable ride on dirt-packed roads.

- Engine: The R80 G/S was powered by a 797cc air-cooled flat-twin engine that provided plenty of power and torque, ideal for touring and adventure riding.

- Durability: BMW had a reputation for building rugged and reliable motorcycles, and the R80GS was no exception. Its tough build quality and robust components made it a popular choice for riders who needed a motorcycle that could handle tough conditions.

Overall, the BMW R80 G/S was a highly capable and versatile motorcycle that offered a unique combination of off-road capability and on-road comfort for adventure riding and touring—and potentially the ideal motorcycle for our intrepid explorer.

But wait, there’s more! One cannot overlook the 1978 Hercules GS250 Enduro, another formidable steed that Humboldt might have chosen for his explorations. This motorcycle, highly praised by the Cycle World editorial team, was lauded as a remarkable fusion of docility and performance, meticulously crafted from end to end on a “rock of Gibraltar frame.” So intrigued were they by its innovative seven-speed transmission that they embarked on an almost obsessive quest for understanding, disassembling and reassembling the entire machine in what might be the most detailed motorcycle review in history.

“The new engine uses two transmission shafts and a pair of idler gears to make seven speeds. The wide selection of cogs combines with the engine’s smooth performance to make the [Hercules] remarkably easy to ride,” they wrote with admiration.

Such an innovative design, coupled with its robust construction, would undoubtedly appeal to an explorer of Humboldt’s caliber. The Hercules GS250 Enduro, with its pioneering spirit and dependable build, would have been a fitting companion for his arduous and exhilarating journeys through uncharted terrains.

The Hercules is not only manageable, they say, it’s also fast.

“Low-gear is low enough for the steepest rock hill and seventh is good for 80 mph-plus on the dry lakes. No one ever knew what gear they were in but it didn’t seem to matter. Another gear is always available above or below if the current selection is unsatisfactory.”

Key features for the Hercules:

- Lightweight: The GS250 was a lightweight motorcycle, making it easy to handle and maneuver, especially in off-road conditions.

- Reliability: Hercules was known for producing durable and reliable motorcycles, and the GS250 was no exception. It was designed to be a tough and dependable bike that could handle extreme riding conditions.

- Affordability: Compared to other motorcycles of its time, the GS250 was an affordable option for riders who were looking for a reliable and capable motorcycle that wouldn’t break the bank.

- Performance: Despite its small size, the GS250 was a powerful motorcycle that offered outstanding performance, especially in off-road conditions.

Overall, the 1978 Hercules GS250 Enduro was a well-rounded motorcycle that offered an impressive combination of affordability, reliability, and performance, an exceedingly versatile and capable bike. It seems we have a win with either of these motorcycles; however, the Hercules, with a dry weight of around 133 pounds (60 kilograms) less than the BMW, possesses a lightness that could make a mountain of difference in the perilous and difficult excursions ahead.

“It isn’t often that we lay hands on a bike that everyone likes, but the Hercules definitely meets this description. It’s not surprising when you think about the package. How often does a new bike employ the absolute best available components attached to a Rock of Gibralter frame and swing arm.”

After missing the boat to rendezvous with Napoleon Bonaparte in Egypt, Humboldt found himself with an unexpected opportunity. Spain agreed to let him tag along with their ship to South America. The Hercules would make its way as cargo across the Atlantic aboard the Pizarro, the large wooden ship setting sail from Spain to Venezuela, likely tucked below deck, tightly secured alongside the horses.

Debarking to this strange New World, Humboldt’s Hercules would need to carry some of the delicate 42 instruments he brought from Europe, packed away in velvet-lined boxes. Among these were a hygrometer made of whalebone and hair to measure humidity, a snuff box sextant to measure angles accurately even while in motion on a boat or horseback (or iron horse, in this case), various telescopes, barometers, magnetometers, electrometers, and a cyanometer to measure the blueness of blue, such as that of the sky and the blue flames inside a volcano he subsequently risked his life to measure.

Humboldt wasn’t solely interested in empirical data; he believed in experiencing nature through feeling and curiosity. This is precisely why, within the caldera of the active Pichincha volcano, he crawled down to a precarious, narrow ledge to measure the blueness of the flames within. This might seem baffling (now just as it did then), but to be fair, a volcano venting electric-blue flames is a stunning phenomenon of nature, rarely seen to this day. Rationally explained by the combustion of sulfuric gases, it nevertheless inspires magic in the hearts of those who witness it.

Landing in this strange new world, Humboldt’s perception of a stable reality was shattered when Cumana, Venezuela, was rocked by an earthquake. What if, rather than having his feet planted on the trembling earth, he was instead ripping through the backcountry of Venezuela on his Hercules, not feeling so betrayed by the instability of the ground? From there, he’d load his Hercules onto a canoe, paddling some of the 1,400 miles he would eventually traverse on the rivers of the Amazon rainforest. A burdensome load in the small boat to be sure, but worth its weight in gold, since without it, they ran out of provisions and nearly starved to death, surviving solely by eating insects, ground-up wild cacao beans, and drinking river water.

Back on Chimborazo, Humboldt’s summit attempt in 1802 ended in failure. According to local Andean lore, Chimborazo is sacred, and the mountain herself will reject anyone who has failings or is considered a “bad person.” They say that if you’ve done something malicious in your life and you attempt to climb, you won’t make it. You’ll end up blind, crazy, or dead.

Beyond his many contributions to science and culture, this might be the most inspiring facet of Humboldt’s legacy. People told him that not only he shouldn’t but he couldn’t, that his curiosities should not be pursued, that he should turn back, that it was a bad idea—and yet he went anyway.

I resonate deeply with his stubborn grit. Any woman who enjoys solo motorcycle exploration abroad, as I have, must regularly overlook the many well-intentioned warnings and statements of doubt from others. Humboldt’s spirit of perseverance and desire to experience the world in a tangible way applies to all motorcyclists, as we make our way through the elements, embracing the wind and touching the earth. In the Western world, riding motorcycles is a choice that many people may try to talk you out of or express their disapproval toward. If you’re a rider, you’ve likely experienced this. And if you’re still riding, it means you’ve pushed through it. You have faith in yourself and your abilities, and you accept the inherent risks that come along with riding.

Too often we succumb to the fears whispered by others and impose self-limiting beliefs, despite our potential to accomplish far more than we ever imagined. Chimborazo may be the nearest point on land to the moon, but with two wheels, a tank of gas, and a Rock of Gibraltar frame, we can stretch into the unknown and ride far beyond the boundaries of our doubts.

It is at the junctures of adrenaline and uncertainty, as we navigate twisting roads and unexpected challenges, venturing over volcanoes and through glacial hailstorms, that our minds can tap into a wellspring of unconventional solutions and ideas. Motorcycle riding demands that we embody our imagination and inventiveness, for it is in those freeing moments on two wheels that our focus has the potential to draft new possibilities.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ITNLTIU5QZARHO733XP4EBTNVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)