Daytona, 1995. It’s still there, in my head, rich and vivid and immediate, almost as if it happened last month.

But it didn’t happen last month. It happened, amazingly, more than 21 years ago. Somehow, my memory remains sharp, so I guess the Alzheimer’s that’s bound to get me eventually after all those crashes hasn’t quite gained a foothold yet…

Looking back, it’s hard to believe the degree of pure craziness and angst we achieved during that particular Bike Week. Or, that such craziness was part of my very first experience into the vintage-racing world. Fortunately, it all ended well, with a little luck and some help from some new friends. More importantly, though, it laid the foundation for two decades of vintage-racing adventurism in the years since.

It all began with an innocent little phone call, which landed on my desk in October or November of late 1994. I was about eighteen months into my stint as Editor-in-Chief of this magazine, after Art Friedman had asked me to replace him so he could actually get back to riding motorcycles and writing stories. On the phone was a DC-area guy named Jack Seaver, who I didn't know from Adam. Seaver introduced himself, established that he was a longtime enthusiast, and got right to the point. He and a few of his Washington-area buddies, plus a vintage racing legend by the name of Todd Henning, wanted to build a racebike and have me compete on it at Daytona in the 500 Premier class that following March and write a story about it.

I was immediately interested, as it’d been roughly four years since I’d done any actual roadracing, my last stint having been at the WERA 24-hour West at Willow Springs aboard an RC30 with Rich Oliver, Randy Renfrow, Mike Spencer and Andy Leisner as teammates. I also hadn’t ridden at Daytona since I did a couple of 600 and 750 AMA Supersport events there in ’88 and ’89 (I got 13th in both races), so that was attractive, too. I really liked riding at Daytona. It was fast. It was legendary. And I loved the beginning-of-the-year excitement of being and racing at Bike Week. I missed the riding and teamwork necessary to make a racing weekend successful, so I said yes.

Seaver’s idea was this: His buddies, primarily Patrick Bodden, RL Brooks and a couple others, would build the bike and get it to Daytona. All I’d have to do is sign up, show up, and ride. Hey, I’d been a magazine editor since ’85 and had attended untold new-bike launches all over the world. I was pretty good at the show-up-and-ride thing.

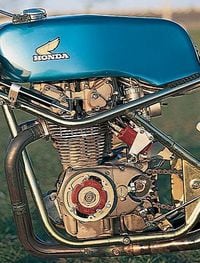

The bike – or the primary parts to build it – would come from Henning, a hugely successful builder and racer from Cape Cod, Massachusetts. (If Todd's last name is familiar, it's because he's the father of Motorcyclist staffer Ari Henning.) Todd had been racing and winning on a Drixton-framed 500cc Honda twin for years, and Seaver and Bodden's idea was to build an identical machine for me to ride and race – and then return it to Henning afterwards. Henning agreed to supply a built engine and frame kit, and through my and the magazine's aftermarket contacts, we'd secure many of the other parts we'd need – shocks, tires, bodywork, wheels, instruments, clip-ons and controls, etc.

The problem was time. This was November, and the race was in early March. “Can you guys get it done in time?” I asked Seaver. “We’re sure gonna try,” he said. Cool.

Out on Cape Cod, Henning began building the engine, using the same basic parts and porting he'd used to win Daytona earlier that year on his own Drixton-framed racer. Countless hours in his shop and on the ACS Racing dyno had netted over 60 rear-wheel horsepower, an astounding amount for an engine capable of just 30 ponies in stock form.

While the engine came together reasonably quickly, the chassis was another story altogether. For a host of reasons it would be weeks before all the needed parts arrived at Bodden’s Alexandria, VA, workshop, where he and Brooks and Seaver (and others) would piece things together. There were hold ups and plenty of cracks for bits to fall through. By the time everything had arrived, there was precious little time to finish the bike and road test it, and despite a few all-nighters leading up to the day they loaded up and headed south to Daytona, the bike was only 80% done. Several components, such as the exhaust, front brake and bodywork, had yet to be fitted and de-bugged.

This was typical Bike Week stuff, Daytona morphing into a time/space black hole – familiar to most who've raced there – that sucks up every available minute, leaving everyone stressed-out, pissed-off and tired. But even that realization didn’t make anyone feel any better about it.

The thrash to get the bike race-ready continued once we'd convened at the Speedway in garage No. 21 on Saturday morning, March 4. Our plan was to use the two days of AMA/CCS racing as practice, but with our bike still not ready to roll, we ended up using both days (and nights) to finish the actual construction. And, man, what freakish sights, sounds and circumstances developed during those 48 hours for any passersby lucky enough (ha!) to peer into our plywood cave that weekend: Half a dozen vintage racebikes (most of them Henning’s), all in various states of (dis)repair: yanked-apart engines sitting on the bench; Bodden's lathe – yes, a lathe! – spinning constantly; rags, safety wire, tools and other race-waste strewn about the floor; welders and torches flashing in the dark; bleary-eyed friends and crew members sleepwalking through the rubble; hope and despair trading places by the hour.

By late Sunday morning I’d still not gotten a chance to ride the bike, and Henning, knowing I’d blow a gasket if I didn’t get on track at least once before the AHRMA events began the following day (Monday), let me ride his personal Drixton for the final CCS practice. I got four laps, and while it wasn’t much, it did give me a glimpse into what I’d be dealing with the next day.

To try to ready our bike for Monday’s AHRMA events, Bodden, Seaver and crew pulled an all-nighter at the nearby American Motorcycle Institute (AMI) campus Sunday night. I bought coffee and McDonald’s cheeseburgers by the bag to keep everyone going. It paid off, because on Monday morning the aqua and gold No. 200 Drixton Honda actually fired! We'd finally get some practice.

Well, a little anyway. Our first session lasted just three laps after a valve-adjuster locknut came loose. Also, the trick, four-shoe Fontana front brake needed far more than three warm-up laps to seat before it would slow the bike forcefully, and the front tire had munched the leading edge of the lower cowl, blasting a chunk of fiberglass under braking. The second session wasn’t much better after the adjuster nut came loose again. We got just one lap, and we’d end up missing Monday’s program.

That evening we fixed the fairing, changed rocker spindles (which had caused the adjuster problems) and wired the adjuster nuts. But as the team slapped everything together early Tuesday morning, hurrying to get the bike ready for our final session, Henning discovered that the cam chain had jumped a tooth, and that the valves were hitting the pistons. We'd missed our last practice. We'd hit bottom.

I blew up, yelling a few choice things and walking away from the entire affair for a good 45 minutes to cool off. Here I was, my first race in years, in what was arguably the most visible and important vintage race of the season, in vintage road racing's most prestigious class, on a bike with race-winning potential … and I'd be racing – racing! – with just five laps of practice. Not good for me or our time-consuming and expensive efforts over the last few months. Plus, with so few laps on it, the bike was sure to have teething problems in the race that afternoon. What they would be, or how they would affect (or kill) me, I had not a clue.

Luckily, AHRMA helped out by allowing me to run our bike in an early race on Tuesday, about an hour before the 500 Premier race. We’d start at the back of the grid, not get in anyone’s way, and use the laps as practice. The bike seemed strong, and the suspension changes we’d made seemed in the ballpark. That was the good news. The bad news came a lap later when the shift lever broke at its weld point. Frustrating to get just one lap, but better than no laps at all.

With no previous AHRMA points, I was gridded on row 12, the last row, about 50th. I could see Henning way up front in row two, 100 yards ahead, with Chuck Huneycutt on a Barber Racing G50 nearby. Despite my back-row starting spot I got a good jump at the flag, the bike launching hard past many of the bikes in front of me.

Lap one was a whole bunch of bazaii craziness as I ripped past 10 bikes in turn one, five in turn two, maybe 12 to 15 more by the time we hit the banking. By the time I flew into the back-straight chicane on lap one, I was in the top ten. And three laps later, after passing Kurt Liebmann (also Drixton Honda-mounted), I was third. By that point, however, Henning was a ways out front.

Those first few laps were practice, really. I was getting to know the bike, how it stopped, turned, accelerated and behaved at speed. Sticky Avon tires and plenty of cornering clearance helped me slice big chunks off my lap times each time around. The Drixton was light, flickable, roomy and surprisingly fast – and great fun to ride. And once the tires got hot, I found I was able to slide the thing a little through the faster corners, meaning I was right at the limits of traction.

By the lap five I began closing on Barber Racing's Chuck Huneycutt, who was second aboard a hellishly fast Seeley-framed G50. By lap six I was all over him, and shocked to find that we'd closed dramatically on Henning, who was having trouble with lappers. I finally made the pass for second entering turn four, though Huneycutt used the speed of his G50 to draft back by me a lap later on the back straight. But we were right there.

With one lap to go, the three of us were pretty much nose to tail as we ripped past the white flag. Did I actually have a shot? I closed the gap further through turns one, two and three, and once again went underneath Huneycutt for second in the West Horseshoe with a sketchy, hairball move between him and a lapper. I bungled the drive out, though, which allowed Huneycutt to pull even with me as we drag-raced to turn five, the all-important left-hander that led onto the banking.

I remember strategizing at that point. I could be patient and go for the draft – and maybe the win – heading into the tri-oval (a common Daytona win tactic) and drafting him. Or I could maybe zap Huneycutt here in turn five, maybe mess up his momentum a little, and put a bit of distance between us so the power of his G50 – and the all-important draft – wouldn't allow him to get back by me at the finish.

I went for the pass, knowing he had a little motor on me and not sure I could draft him (and maybe Henning) at the finish. I was certain I'd be able to out-brake him with a Butcheresque late-brake maneuver entering five. But he hung in there (damn, Chuck!), and more importantly, he had the inside line, which I realized a bit too late in the game. We hit the brakes simultaneously, both of us chattering and skidding toward the apex of turn five.

But he had me, and we both knew it. And just as I'd have done, Huneycutt drifted a little wide, forcing me to either back off (handing second – or the win – to him) or end up on the grass, flat-tracking. Not willing to back off, I did the latter, which killed any chance of me winning, or even making it close.

Henning won, beating Huneycutt to the flag by a bike length, and I was third, 10 or 12 seconds down.

Still, the cool-down lap was an epic experience. Fans and corner workers stood and waved; I got a high-five from Henning as we coasted to a stop on the hot pit lane; endorphins rushed into my system after the maximum, mind-burning effort; my Dad wore a jumbo smile, as did our entire crew; and as I took off my helmet on pit lane, ex-racer and race announcer Richard Chambers came over to interview me on the PA system. I'd raced for 20 years, but had never felt quite as good as I did at that moment.

At post-race tech, AHRMA officials extracted fuel (for testing) from my bike's tank, and we learned later I had maybe six ounces left. That extra splash Jake Carlton had put in as we left the garage an hour before had kept us alive. And that nut and bolt Patrick had installed on the brake-lever pivot just in case the clip fell off? Well, the clip had fallen off. Just two more little miracles supporting the major miracle of our team actually getting this bike on track and into the race, come hell or high water.

There was Mexican food and drinks that night, although soon after most of the crew had gone back to their hotels to sleep – something they’d gotten very little of in the previous week. They sure earned it.

For me and for the team, Daytona 1995 was amazingly frustrating, and a lot of work. But it was also amazingly gratifying – in the end, at least. Achievements tend to be richer and more satisfying when they’re hard earned, and this one was definitely that.

The best part for me, really, was the foundation this Daytona experience formed. Not only for vintage racing, which I’m still doing (mostly in the dirt, of late), but for the friendships I developed there, especially with Henning, Seaver, Bodden and Brooks. For the better part of a dozen years after that Daytona I was still doing vintage-racing stuff with those guys at tracks around the country and the world. Daytona. Grattan. Sears Point. Barber. Mid-Ohio. And overseas, at Silverstone, Mallory Park and Goodwood.

Good times, for sure, and ones I will never forget – at least until Alzheimer’s pops up after all my crashes and erases my memory banks.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZNEDZMRSZIMZZAMLN2LMUM3C24.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)