It's a story I've probably told more than any other in my 32 years of magazine work, and for good reason. See, this is much more than one of those rare, vintage-racing comeback stories, where the team rallies – like we did at Daytona in last month's "Miracle in Garage 21" piece (click here) – to win or at least finish after monumental odds. (All that "monumental odds" business is true, of course, thus this story's title.) But there was a lot more to this trek to beautiful Grattan Raceway in the summer of 1996 than is obvious on the surface – which is why I end up telling the story more than a few times each year to friends and long-time readers.

Yes, there was a dramatic comeback from a broken motorcycle. And my race on Sunday against a Midwest supersport-racing hotshot named Dave Rosno remains without a doubt the finest 10 laps of my life. But there was more, much of it surrounding a bearded, crusty-looking older gent at the races that weekend with the nickname of Rocky Solo.

From the beginning, then…

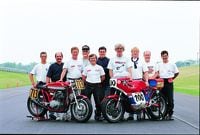

Coming off our experiences at Daytona the previous year with Todd Henning and the Drixton-framed Honda CB450 racer (see "Miracle in Garage 21, Revisited"), our band of vintage idiots – Jack Seaver, RL Brooks, etc. – obviously didn't get enough of the bile, consternation and angst that's often part of the vintage-racing experience – for us, at least. We'd gone to Daytona in '95 with a totally new, untested motorcycle and paid the price trying to finish assembling – and then de-bug – the thing, and with only a few laps of practice.

So what did we do for ’96? We went to Daytona with a motorcycle that, once again, wasn’t quite ready for prime time. Of course, it all ended up being a moot point when I broke my arm and separated my shoulder in an ugly International Horseshoe high-side during a Triumph Speed Triple race that weekend.

Our follow-up plan with our new 750-class race bike was to do AHRMA’s double-national event at Grattan, Michigan, later that year. The bike would be fleshed out by then (or so we hoped) and my arm and shoulder would be healed up. And since I’d never actually raced at Grattan (I’d gone there 20 years earlier as a kid and rode my XR75 “roadracer” in the pitbike race), I was excited about the opportunity.

The bike I’d be riding this time around was a highly modified 750 Honda with a beautiful Dresda frame, the Dresda name coming from a Brit by the name of Dave Degens who ran a company called Dresda Auto in London during the late ’60s and ’70s. Degens’s frames were highly successful in racing, with a Dresda-framed CB750 winning the 1972 Bol d’Or at Le Mans.

The rest of the bike was as spectacular as the frame. Noted east coast engine builder Eugene Klymenko, who was close with Pops Yoshimura back in the day, did much of the engine work and used all sorts of trick stuff: Kibblewhite valves, a Falicon crank and Megacycle cam, Barnett clutch, Hindle exhaust, LA Sleeve cylinders, etc. Special Dunlop tires, Lockheed brakes, Race Tech fork work and Works Performance shocks helped out on the chassis side, with beautifully painted Air Tech bodywork wrapping everything up nicely. It was one of the nicest project bikes I’d ever been involved with.

The Grattan AHRMA event was a 2-day affair, what’s called a double National, with the same schedule of races on both days. I’d be running in two different classes that weekend, Formula 750 and Formula Vintage, the latter class allowing F750, Formula 500, 500 Premier and other Sportsman-class machines.

On Saturday, I got in a good bit of practice before my first race, the Formula 750 event. I won that one, beating longtime roadracer Kurt Leibmann on his CR750 – another kitted 750 Honda – to the line. Thirty minutes later I was again on the grid, this time for the Formula Vintage event. I got a fairly good start and moved into the lead about halfway through the first lap, and as I ripped up the hill onto Grattan’s front straight, I figured I’d have an easy time of this race, just as I had earlier in the day.

Problem was, the engine broke loudly and disturbingly at redline right as I flashed by the pits. I yanked in the clutch lever as soon as I heard and felt those first sickening whack-whack noises, though as I rolled quietly past the scorer's tower and saw oil coating my left boot, I knew we were in trouble.

I leaned the bike against the guardrail, hopped over and took a seat on the grass. Jack Seaver, the architect of this whole Formula 750 business, trotted up a minute or so later, out of breath and looking even more harried than usual. He didn't say anything right away; he was hoping, I think, that it was something simple, like an electrical glitch. But after I shook my head and pointed to my oily boot, Seaver got the picture and began pushing the dead Honda back to the garage.

Sitting there with the other bikes roaring past, I thought back to all the hard work and headaches it had taken to get here. The crazed effort to finish the bike for Daytona (AHRMA's season-opener); the frustration of not being able to compete there due to my arm-breaking Speed Triple crash; then the agonizingly long three-month wait to heal until the Grattan event. And all for this: one measly race, a single win, a fragged engine and a whole Sunday's worth of racing about to be forfeited. Damn.

Thirty minutes later, with the cam cover off, the news was not encouraging. The engine's tacho-drive bolt had come loose and lodged itself under the camshaft, which had pounded it into the head at 10,000 rpm, blasting a hole in the casting, splintering the engine's cam holders and bending several rockers. Ugly. We'd probably be able to fix the cavity with JB Weld, but to race the following day we'd need parts: a pair of cam holders and several rockers, at the very least.

Worse yet, it was late Saturday afternoon by that point, and none of the area's Honda shops or boneyards were open. I scoured Grattan's KOA-style pits, hoping someone had an old CB750 engine tucked away in their van or trailer. But no one did. I even got on the track's PA system, asking for help. Nothing. And just like that, our weekend – which had shown such promise early on – was over.

Back in the garage, our ragtag crew of friends and acquaintances was coming to grips with the fact that we were finished. This was a huge bummer, not just because we'd have likely won more races the following day, but because we'd miss much of the scene that weekend: Grattan's campground-style atmosphere; the late-evening campfires, beers and storytelling; the friendly competitiveness and help-your-neighbor attitude in the pits; the between-race tweaking, the whole juicy scene. Yeah, we could hang around and watch, but it wasn't the same unless you were in the game. Even the AHRMA-sponsored barbeque that evening didn't help ease the pain.

A bit later, with the food and beer mostly gone, a skinny, crusty-looking guy with a whitish-grey, ZZ Top-esque beard turned up at the entrance to our garage. He looked to be in his late 50s and, like most of us, was nursing a beer. "Which one of you is the magazine editor?" he asked, slurring his words just a little.

"I am," I said, taking another swig on my own bottle and wondering just how many beers this guy'd had.

"Heard you're lookin' for some Honda parts," he said, "single-cam CB750 parts." The garage went silent in a hurry. "Well, I got plenty,” he said, “and you're welcome to 'em. But I want to say something first...."

Before I could digest all of this, our bearded visitor launched into a sermonlike assault on me and the entire motorcycling press. All motorcycle magazine editors were the same, he said, all evil, all elitist, all "on the take" from the Japanese manufacturers and not to be trusted. We criticized perfectly good motorcycles in print, he added, and we never, ever wrote about the great British bikes of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. He finished with this: "I've had my say here. If you people want it, I've got a pretty good 750 Honda down on my farm. It's a ways from here, so if you want it, we'd better get going."

I took most of what he said personally, of course, and was about to tell him where he could stick that beer bottle when Seaver popped up beside me. "Just ignore him," he said quietly. "If he really does have the parts we need, we might be able to run tomorrow." I flashed back to Obi Wan Kenobi, telling the storm troopers guarding the entrance to Mos Eisley Spaceport that these weren't the droids they were looking for. "Look," Seaver added with a grin, "it'll be an adventure." Taking this old codger's crap was the last thing I wanted to do. But I took it. I wanted to race the next day.

Ten minutes later, I found myself in Seaver's van, Jack, myself and our "friend" heading southeast toward the Lansing area. The guy mentioned his real name, but it was his nickname – Rocky Solo – that stuck with me. He said he was a postal worker, a long-time motorcyclist and a bit of a collector. He was also a major-league ass, messing with me for much of the 100-mile trip and asking to stop for beer every few minutes. (We ignored him.) I ripped him back a few times (which made me feel better), but at about the halfway point I actually began thinking that, once we'd gotten the bike (if there even was a bike), I’d beat him good and toss his sorry ass out of the van.

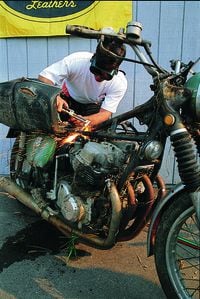

Ninety minutes later we arrived at Solo's home, a shoddy farmhouse with a few ramshackle barns in back. As we pulled into the uncut rear yard, Solo pointed at the bike, which was visible only by its left handlebar sticking up through the knee-high weeds. It turned out to be a CB750, sure enough, a forest green one, probably a '72 or '73. It was laying on its right side, stuck in the mud, weeds and grass growing though the frame rails, Michigan muck squashed into the cylinder block. It took all three of us and a 12-foot piece of lumber to lever it up out of the mud and jam it into the van. It was a mess, which was obvious even in the fading light.

"It looks like junk," Solo said, "but most of the top-end parts are new." I figured he was full of it. The thing was rusty and broken and totally roached, missing a slew of components, and if there were fresh parts in the engine then I was Kenny Roberts. Of course, there was always the possibility the guy was right, so I kept my mouth shut. This was not easy.

But before we could leave, Solo insisted we take a look at his collection. Spending time with this geezer was the last thing I wanted to do, but Seaver figured we owed him, so we headed off toward the first barn.

Surprise number one: Inside were hundreds of old bikes, most from the '60s, many of British origin, most of them rusty and decrepit. But he had some gems packed in there, too, real rare and obscure stuff that Seaver went bananas over. Solo seemed to have a story for each one, which he took his time telling. "Kept every bike I ever bought," he told us. Turned out the guy did know his bikes.

As we were walking through the last barn, which was clearly his workspace, I spied an old picture frame propped up on one of the workbenches. The black-and-white photo inside was of a young soldier cradling what looked like an M16 in his arm, an ammo belt slung around his shoulder, standing with four or five similarly attired Asian soldiers, [the look] on each of their faces.

It was Solo, standing with a bunch of South Vietnamese Army regulars. I’d read enough books on Vietnam to know. Suddenly, I got it: The hostile, pissed-at-the-world attitude, the dark sense of humor. It all made sense. The guy (as I was to find out later on the trip back to Grattan) was an ex-Marine, a Vietnam vet, and not an R.E.M., either, but a search-and-destroy grunt, a hardass, a guy who'd survived the ambushes and booby traps and tunnels. He'd been obnoxious and rude, and had some bizarre opinions about life, but knowing a bit of his background softened my outlook some. (I also promptly forgot about beating his ass and tossing him out of the van.)

While we'd been retrieving Solo's bike (which Seaver and I named Swamp Thing on the way back to the track), Eugene Klymenko and the guys had gotten the engine ready just in case our little parts hunt proved successful. We arrived back at our hotel at around 1:00 am, got everyone together for a quick meeting, recounted the whole crazy recovery story, and decided to get some sleep and get cracking at first light. Luckily, my two races weren't until Sunday afternoon, so we'd have some time.

The following morning and early afternoon were a blur – a manic thrash to get the bike fixed and back together in time for the first event. We dug into Swamp Thing first to retrieve the engine parts we'd need, Steven Spitz cutting away various frame braces with a blowtorch to get at the top end easier. We lifted off the valve cover and, sure enough, the parts were like new, just as Solo had said. The guy's reputation jumped yet again. Fresh valve train parts in hand, Klymenko went to work on the engine.

Ten feet away, someone re-brazed the frame, which had cracked near one of the steering-head braces. The sight of the totally stripped frame laying upside down on a milk crate with a torch being applied an hour or two before my race was not calming. By noon, our garage was a mess: Engine and chassis parts were scattered everywhere, folks were running around in a panic, and groups of racers and race-goers were standing in the doorways to see how the thrash was going. It all reminded me of our original "Cardiac Kids" experience at Daytona the previous year, when we'd gotten our Drixton-Honda racer ready for the 500 Premier event at the last possible minute after some major engine problems.

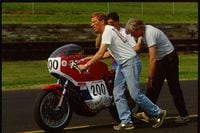

Two hours later, the bare frame began to morph back into an entire motorcycle: first, wheels and suspension, then the engine, then the bodywork. With less than 30 minutes left before my first race (Formula 750, and a rematch with Liebmann), the bike was together. But would it run?

Klymenko fitted the Dresda with the kickstart lever from Swamp Thing. There were probably 30 or so people crowded around the garage doors now, folks that'd been following the rebuilding process all day long. No surprise there; PA announcer (and AHRMA head tech inspector) Jack Turner had been hyping the goings-on in our garage all afternoon. Klymenko kicked once, twice...and it fired! An actual cheer went up. I was stunned. I think everyone was. The thing worked; we were actually back in the game. Who'd have thunk it? I looked for Solo among the crowd, wanting to thank him. But he was nowhere to be found.

The Formula 750 race that afternoon was a good warmup. I got the lead halfway through the first lap and wasn’t ever challenged. Our Dresda-framed CB750 handled Grattan's twisty circuit surprisingly well. It was light (just 368 pounds without fuel), flickable, stable, had killer brakes, was surprisingly fast (82 rear-wheel horsepower), and was easy to ride at the limit, especially with the sticky Dunlop KRs mounted. Considering its vintage, the bike worked a lot better than I'd expected.

Between races I'd wanted to gear the bike a tooth taller so I wouldn't run into the rev limiter at the end of the front straight and between some of Grattan's tighter corners. Seaver grabbed the tools necessary to swap sprockets, but Klymenko, knowing the engine could be spun just a bit faster, simply told him to bump the bike's Dyna-built rev limiter from 9500 rpm to 10 grand. One flick of a screwdriver and bang! – instant gearing change.

My next race was Formula Vintage, which the folks at AHRMA had designed as an ultimate vintage shootout of sorts. The event combined the fastest machines on the track: bikes from the Formula 750, Formula 500, 500 Premier and 750 Sportsman classes. By including F-500 machines, the class also allowed two-strokes – giant-killer 350cc TR3 Yamahas, for instance – to compete, which made the race a bit of a throwback to the earlier days of AMA roadracing and the epic battles between the Honda, Yamaha, Triumph and BSA factories. That was Gene Romero, Dick Mann, Gary Nixon and Don Emde territory.

At the start, I was again able to lead to the first turn with a slicing inside move, though another bike (which I figured to be one of those hellishly fast TR3s by the high-pitched whine it made) beat me to the apex with a crazy, late-breaking move. I assumed I'd be able to zap the smaller bike right away, but as I followed it on the opening lap, I began to wonder. It was not only fast and seemed to rev to the moon, but the guy riding it was an absolute wild man, an expert racer for sure. I had to ride way over my head just to keep up.

I pulled alongside the mystery bike on the front straight to begin lap 2 (the 750, though heavier, had a bit more steam) and was shocked to find that it was a Honda CB400F! I remember actually doing a double take as I went past. As I’d find out later, the bike was owned by veteran builder Steve Spencer, and reasonably well-known in those parts for beating bikes with far more displacement – although Spencer’s ‘Yellow Peril,’ as it was known, was much more than a 400. Anyway, once by him, I foolishly figured I'd seen the last of him, but as I braked as deeply as I dared for turn one at the beginning of lap two, the 400F rider blew past me, flicked the bike into the turn and – while laying down a nasty black streak at the exit – began to pull away.

I knew right then I was in trouble.

This guy – Dave Rosno – was clearly going faster than I was, especially now that his tires were warm, and if I didn't bump my pace immediately, I was gonna lose both him and the race. The next two laps were totally hairball, both of us chattering and sliding through the corners, him trying to get away, me trying to just stay close. But by going to school on him, I learned a couple of his better lines and was able to hang on. Barely.

I got by him two or three more times on the front straight. But each time, Rosno – who was 80 pounds lighter than I was, and whose bike was probably another 50 to 80 pounds lighter – would outbrake me into turn 1 and lead at the exit.

This happened again two laps from the finish, but this time I was ready. When he whipped by me, I squared the corner off, got on the throttle early and got a stronger-than-usual drive off the turn. We hit the next corner side by side, but because I had the inside line (something I learned from Daytona '95), I had him. And I think he knew it.

I led the next two laps...riding harder than I ever had in my life, my forearms pumping up and my grip on the clip-ons weakening by the second. Rosno's heavily modified Honda was right on my tail the whole time – I could hear him back there, the bike seeming to be at redline the entire time – but I was somehow able to keep him behind me. I won by just three or four bike lengths.

I’d never before felt that level of exhaustion and elation at the end of a race, and it hasn’t happened since, either. It was easily the best race of my life, and it felt amazing.

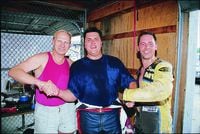

I met up with Rosno in our garage a few minutes later, sweat-soaked and happy, and we had a beer with the crew while we jabbered about the race and how much fun it was to watch one another sliding and chattering all over the place. We certainly both had a bird’s eye view of things.

Thirty minutes later, talking to my dad while still in my sweaty leathers, the elation was all there. We’d achieved a lot more than we'd expected: We'd won every race we finished that weekend, and proven that our bike really was a highly competitive F750 racer. We’d also bounced back from severe adversity, which is always highly rewarding.

And Rocky Solo? I don’t know if he saw the race, and he never showed up for the celebration that evening. But I think he was there in spirit. I never did get a chance to thank him for donating Swamp Thing to our effort, but I think winning those races the way we did was probably thanks enough.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XKQY3BYUKWMCLVQBS4GQ25FOOQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)