On Any Sunday. It's been described as the "most exciting film ever made" on motorcycling. Actual movie critics called it "masterful" and packed with "thrills that can't be described." Most motorcyclists would agree with those assessments of Bruce Brown's epic 1971 documentary, which, amazingly, turns 45 in July 2016.

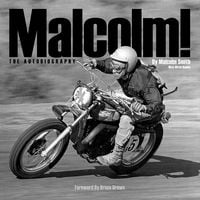

But there are plenty of things folks don't know about the movie and the part Malcolm Smith played—or almost didn't play—in it. As editor of Malcolm's new book Malcolm! The Autobiography, I'm fortunate to have heard a bunch of these behind-the-scenes tales. And because Malcolm's 400-page coffee-table tome will be available by early September (see themalcolmbook.com), Editor Cook and I figured it would be a fine time to relate a few of them.

A key one, I think, is the fact that Malcolm came very close to not being in the movie at all. "It's true," Malcolm says with his trademark grin. "Bruce, who was a customer of mine, came in one day and said, 'Malcolm, I'm just starting on a motorcycle documentary similar to The Endless Summer. Interested in being in it?'

“Well, of course I was interested. The only problem was my new job as the very green owner of K&N Motorcycles, which I’d just purchased from Kenny Johnson and Norm McDonald—who’d go on to build the K&N performance filter empire. I was struggling with management headaches and feeling overwhelmed, so I had to tell Bruce no. Too stressed. Luckily, Bruce came back a week or two later and asked again. And because I’d gotten things somewhat under control at the shop, I told him I was in. It was one of the better decisions I’ve made in my life!” Indeed.

Malcolm was happy to hear that Steve McQueen, also a customer, would be involved. "I liked Steve," Malcolm says. "He was a real motorcyclist, not a poseur. Like me, Steve grew up without much money and was every bit as frugal. He'd make me show him the parts I'd replace on his Huskys!"

Malcolm was excited about the movie but had no clue it would add up to anything more than some fun riding and traveling. “My life at the time was too full of business, my two young children, Luci and Joel, and racing for me to realize the possibilities. It was just another fun project.”

One of the first events Bruce filmed was the Elsinore Grand Prix. “There’d been a lot of rain leading up to the race,” Malcolm remembers, “and I noticed that a section of dirt road had a large puddle in the middle. The first riders—me included—got through the puddle without much trouble, but a lot of the pack got bogged down in axle-deep mud.” The hole would become a topic of great controversy in the outcome of the race.

“I got a great start and was soon leading, and as I approached the mud hole on lap two, I could see quite a few stuck and abandoned motorcycles. I skirted the edge next to the fence where the dirt was firmer, but still slick and muddy, and I had a moment as I ripped through there pinned in second gear, at times using the wheels of fallen motorcycles for traction. But I made it through. I remember seeing officials cutting the barbed wire as I did so, presumably to route riders around the hole onto dry ground for the race’s later laps. For many competitors the mud hole was the end of their race. Everyone was muddy, the goo obscuring many number plates, including mine, which caused scorers to miss many of the numbers, which added fuel to the brewing scoring controversy.

“When Bruce edited the film,” Malcolm says, “he showed me going through the barbed wire and around the mud on dry ground, which gave the impression that I’d cut the course. Of course, by that time, the course had been officially rerouted outside the fence, and what was shown in the movie was actually my third lap, not my second. A close look at that footage shows the mud hole basically empty (which it was not on my second lap), and which it was on the third lap after most of the bikes had been pulled from the bog.

“Anyway, the race results showed me six minutes ahead of second-place Gary Bailey in total time, but missing a lap, therefore removing me from the top finishers. And despite a consensus by all involved that I had won by a wide margin, they never changed their official position. Bruce, of course, got it right in the movie! I wasn’t too worried, actually. Everyone knew I’d won, and I’d had a good time right until I hit a woman crossing the road the following day on a 360 Husky going about 75 mph. But that’s a story you’ll have to read about in the book.”

Back to the movie. “One of the more memorable scenes was the poor guy stuck in the desert who tried to light a signal fire. That was Bruce’s idea, and I had the perfect bike for it—a repossessed Husky with a blown engine. It burned pretty good in the scene, and most folks probably thought it was a total loss. Not true. We repainted the tank, replaced the cables, rebuilt the engine, fitted new tires and seat, and ended up selling it. It’s out there somewhere!

“Shooting the ending sequences was a lot of fun. The scenes themselves—riding with your friends, cow trailing, beach riding, sliding around, goofing off—really did capture the essence of the fun of motorcycling, and Bruce did a masterful job recording it for eternity. Steve was very competitive and always wanted to be out front, which worked well for the cow-pie bit we did. The shots of Mert flinging cow poo off his arm, of me laughing, and of Steve looking back at us with an evil grin are epic.”

Malcolm and Mert got Steve back on the water-crossing scene, which Steve wasn’t ready for the first time they did it. “Steve figured we’d all ride through slowly,” Malcolm says, “but of course Mert and I [and Bruce] had other ideas. We blasted him good, and Bruce, with a cameraman in the bushes, got the shot. We did more versions of it, and Steve got really wet and cold. But Bruce ended up using that first take, which was easily the best of the bunch. Watch the scene closely, and just after Steve spits the water out of his mouth, he turns and you can begin to see the beginnings of a grudging smile. He knew he’d been had—and good!”

The sand dune footage was shot in Baja, Mexico, on the Cantamar sand dunes overlooking the Pacific. "Mert was riding a Greeves," Malcolm says, "but put a Harley-Davidson badge on it to keep his sponsor happy. Bruce didn't have any fixed program; we were just ripping around, having a great time while Bruce and company filmed."

For the last day of filming, Bruce wanted unstructured riding for fun on the beach at Camp Pendleton Marine base. “Bruce called the base for permission,” Malcolm remembers, “and heard this: ‘Absolutely not! No way!’ Steve then called the base commander, who sang a different tune: ‘Okay, Mr. McQueen, anything you want.’ I guess it really does matter who you are!

“The beach riding was really fun,” Malcolm says, “especially the power-sliding during low tide. Crashing on the low side wasn’t too bad. But if you chopped the throttle too much you got high-sided, which hurt. Steve did it several times that afternoon. At the end of the last day we all jumped into Bruce’s hot tub. Steve was a mess… What wasn’t black and blue was skinned up or both!”

With a hundred hours of raw film to process, analyze, and edit, Brown spent the following 10 months crafting On Any Sunday. During that time, Malcolm got back to work and basically forgot about the project. "Bruce never talked about how he'd cut the film," Malcolm says, "so I honestly had no clue I'd be featured so prominently."

The film screened a couple of times in Hollywood and Westwood (UCLA) before going to national theaters. Malcolm attended the early screenings and was shocked to see how much of a role he played. “I was really surprised,” he says now. “I had no idea. And the movie was so good! Bruce did such a wonderful job on it.”

“Malcolm’s always telling everyone that the movie made him,” Bruce Brown says today. “But I think Malcolm helped make the movie. He was the guy with the smile, and he really resonated with moviegoers. Folks expected Steve to be good, and he was. But Malcolm was a star, too, as was Mert. What a team.”

And boy, what a movie.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OPVQ7R4EFNCLRDPSQT4FBZCS2A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YBPFZBTAS5FJJBKOWC57QGEFDM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/W5DVCJVUQVHZTN2DNYLI2UYW5U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/C3VIRIAYNZCTJAZNRLREDS3JCM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XXWKUKITWRAF3HCJAWGJ25V7BA.jpg)