There's a mountain in Colorado whose name rolls reverently off the tongues of racers around the globe: Pikes Peak. For a hundred years, competitors have been tackling the serpentine road ascending the 14,110-foot pinnacle in the legendary Pikes Peak Hill Climb, or as it's sometimes called, The Race to the Clouds.

I've been fascinated with Pikes Peak since I was a kid but never visited the mountain until the day before the 2016 event, when I rode a Victory Octane to the summit of the famed peak. Passing through the official start/timing gate at 9,390 feet, I began the 4,000-plus-foot climb through the 156 corners that comprise the point-to-point course. The event workers had just completed final prep, and many of the sections were bordered by neatly aligned hay bales with vinyl covers freshly emblazoned with sponsors' names and the Pikes Peak logo, brightening my ascent with colorful touches of racing set against a backdrop of pine trees. The atmospheric conditions changed dramatically over the ensuing climb, transitioning from warmth and sunshine to wind-driven cold, with an increasing threat from the darkening skies culminating in thunder and lightning at the summit. It was a firsthand study of the race's famously adverse conditions.

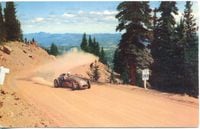

Ascending Pikes Peak, it’s easy to become entranced by the way the corners wrap around the mountain and to try to figure out how the curves could be taken at speed and woven together into one, sublimely committed run. Like the beautiful sirens that lured sailors’ ships onto the rocks with their enchanting songs, the narrow Pikes Peak road seduces you, masking the danger posed by the lack of guardrails on the upper sections—only the thin, blue Colorado sky stretching out beyond the edge of the pavement. It’s all just part of what makes Pikes Peak the event it is.

Pikes Peak was named after Zebulon Pike who in 1806 was the first explorer to attempt to climb it. The attempt failed, leading Zebulon to declare that the mountain could not be climbed. Sixty-seven years later, in 1873, the Army Corps of Engineers built the first primitive road up the mountain to service a weather station installation. The road, which ascends all the way to the summit, subsequently became a natural proving ground for the bourgeoning motorized-vehicle craze of the early 1900s. The Reading Standard Company used the mountain to prove the worth of its R-S Motor Bicycles, taking three bikes to the top in 1906.

In 1916 entrepreneur Spencer Penrose, who made his fortune in gold and silver mines, organized the Pikes Peak National Hill Climbing Contest to publicize his new Pikes Peak Auto Highway, one of his many ventures—this one intended as a tourist attraction. The first running of the timed event attracted a host of cars and motorcycles. The 12.42-mile course is virtually the same layout today as it was then, except that instead of the original gravel surface the course is now paved—a $15-million, 10-year process begun in 2002 and completed in 2012. The intervening 10 years, while the course transitioned from gravel to pavement, resulted in some spectacular racing.

In 2016 the 100th anniversary of Pikes Peak was celebrated along with the 94th running of the Pikes Peak Hill Climb, giving it the distinction of being the second oldest motorized event in America; only the Indy 500 is older. Over the years the race has been canceled seven times, the first three during WWI (1917–’19) and another four times during WWII (1942–’45). Maybe Zebulon Pike’s claim that the mountain couldn’t be climbed set a precedent for how impossibilities can be overcome because 210 years later the mountain is annually consumed in efforts not just to crest the summit, but to shave off time in increasingly rapid, motorized dashes to the top.

The first motorcycle to take to the mountain in an official run was in 1916 at the event's inauguration, when Floyd Clymer piloted his Excelsior to the summit in a record 21:58.410—just less than 22 minutes to cover the 12 miles from start to finish. For autos, the winning time for the inaugural event was 20:04.60. In the hundred years since a stopwatch was first clicked to record a run, the times have dropped dramatically. The standing two-wheel mark, set by Californian Carlin Dunne in 2013, is 9:52.819. The fastest overall time to get up the hill was also set in 2013, by Frenchman Sebastien Loeb, who crested the summit on four wheels with a blistering time of 8:13.87. That's roughly 12 minutes faster than the original two- and four-wheel times set in 1916.

As the event grew over the decades, an increasing number of motorcycles took to the mountain; the two-wheel division started in waves, with as many as three groups of 40 competitors each. The resulting dust and mayhem of the mass starts and gravel surface contributed to a lot of crashes. In 1982 a rider was killed, and bikes were banned from the event. Motorcycles didn’t return to the mountain until 1991, using the same staggered-start timed format as the cars.

The elevation difference between the start and the finish provides starkly contrasting conditions. The weather on one part of the course may not be what’s happening elsewhere. Wind, calm, dry, rain, heat, cold, sun, clouds, grip, and lack of grip are all possible scenarios—not over the course of a day, but in a single run—and can change moment by moment.

Practice and qualifying are unique. The course is broken down into three sections, with one day of practice on each section. Only on race day do racers run the entire course. It’s a test of concentration, memorization, and visualization, and there’s no warm-up on race day. Arrive in the early morning cold, line up at the start, and drop the clutch.

Roadracer Jeremy Toye first visited Pikes Peak in 2014, becoming King of the Mountain his rookie outing with a time of 9:58.687. Jeremy was in the saddle of Victory’s Project 156 for the 2016 event, applying his knowledge of the mountain to getting the big American V-twin-powered machine to the top.

“The distance isn’t super long,” Toye explains. “We’re dealing with 12 miles. For practice they break it up into three sections. Those three sections are massively different. No exaggeration, you could technically build three different bikes, one for each section. Having a bike to go across all three is a bit of a chore. Not only that, but having the mental power to remember how to ride the aggressiveness of all three is a challenge. I’ve got a printed-out map of the place with some notes on it, and I’ll go through it in my head and flash-card it. I’ll cruise it in my brain.”

Toye has raced the Isle of Man, which is often compared to Pikes Peak because it runs on public roads and features radical weather. “Sections of the top [of Pikes Peak] are more violent than the Isle of Man, more bumpy,” Toye says. “You don’t have the high speed, but you have the technical parts. The accuracy is probably higher because the speeds are lower, and the course is tighter.”

When asked about the effect of the extreme elevation change of Pikes Peak on both body and machine, Toye says, “Physically I go okay, but for sure it will slow your thinking down, that’s a proven fact, but it hasn’t seemed to effect me. I don’t know what it is. I think you get that adrenaline going, keeps you going to the top. Bike-wise, you can see it a little bit, but modern fuel injection and modern engines do a good job with elevation.”

The Pikes Peak Hill Climb is hard on spectators as well as racers. You find your place and settle in for a full day of watching everything from motorcycles to quads, racecars to semi-trucks. But because the road is shut down for the day, with no alternative routes off the mountain, wherever you settle in is pretty much where you’ll be for the duration. They say it’s possible to get frostbite and sunburn in the same day, so hardcore fans—of which there are many—have learned to come prepared to deal with any and all conditions. The Pikes Peak regulars are some of the most hardboiled and devoted fans I’ve seen anywhere.

On race day in 2016 the mountain was cold. The planned start for motorcycles—the first vehicles to go—was delayed for an hour to allow the ice that had formed overnight on the upper section to melt. Jeremy Toye was the sixth rider to start. At 8:39 a.m., Toye thundered off the line and scattered birds from the pines as he wove his way up through the tree line. When he reached the upper section he encountered a good deal of wet racing surface due to the melting ice. The slippery conditions forced him to slow down, ending up with a time of 10:19.777. Ten minutes later a crash brought out an extended red flag. When the racing resumed, a full hour had passed, allowing the sun to warm the pavement and dry up the melting ice of the morning, resulting in more agreeable conditions for the racers who had yet to run. But that’s racing. In the end, Toye’s time was good enough for third overall motorcycle and a win in the Exhibition Powersport class.

Another aspect that Pikes Peak shares with the Isle of Man is that because of threats of litigation from overzealous government agencies and private law firms, combined with increasing outcry from a dispassionate and apathetic public, the event is in danger of becoming extinct. As with the Isle, every time there is a serious mishap (sadly, there have been fatalities) the local papers stir up the general public, which immediately begins calling for an end to the event. Some of the longtime devotees of the event fear that the clock is ticking in more ways than just timed runs.

So if you’ve ever dreamed of experiencing the Pikes Peak Hill Climb firsthand, you’d best be advised not to dawdle too long. The famous race might succumb to pressure from entities that aren’t exactly enamored by the allure of living life through the excitement of racing. All they see is some statistics about the dangers that result. Until that time comes, rest assured, racers from all over the world will continue to catapult themselves into the clouds, chipping away at those standing records.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/SJYLNJVHHVO6JW6BXDOOPOLOKM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)