Editor's Note: Our first contact with Keith Kimber and Tania Brown came in early 1998 when a thick and tattered manila envelope arrived at our office. In it was an outline of an almost unbelievable around-the-world story, and some of the most stunning bike-touring photography we'd ever seen. Turned out that, way back in 1983 the pair had, in their early 20s, quit their jobs, bought a well used CX500 Honda for $1400 and taken off to see the world. We were so impressed with their tale we published a large chunk of the story in our April, 1999 issue. By mid 1998, Keith and Tania were heading across the United States toward Alaska and a new chapter in their (now) 18-year, tour the world by motorcycle adventure.

By 1990, we'd already been around the world once. Now we were stuck in Cyprus, the Gulf War cutting off our route through the Middle East to Russia, the next leg of our journey. What we really needed was a boat. We looked for a working passage, but couldn't find a ship traveling that route. Then, one day, Tania walked into a marina and found a 31-foot, 35-year-old wooden sailboat--one full of holes. We knew absolutely nothing about sailing. But with the last of our savings we bought the boat, fixed the holes, dismantled our bike, stored the pieces on board, and sailed away from the war in the Middle East by traveling West--across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States.

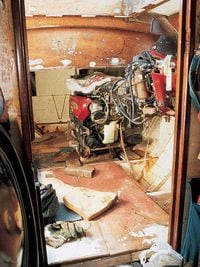

No sane person would want to dismantle his or her beloved motorcycle and store it in a leaky old boat. We certainly didn't; after all, it was a perfectly good motorcycle. But we did. To get our CX500 on board, we disassembled it on the dock (with quite a crowd watching) and had to squeeze each bit through a hatch the size of a TV screen. The frame was the tightest squeeze; we had to twist and turn it to get it through.

For the next six years, seawater leaked all over our CX, and for long periods the engine itself was submerged in bilge water 8-10 inches deep. Everything corroded. The wiring loom turned to mush. (Now, why couldn't I have destroyed my perfectly good motorcycle by crashing into the side of a truck, or spinning off the road at high speed like any normal biker?)

By the time we landed in Florida and took the CX out again--piece by corroded piece it was nothing but a pile of scrap. It took a whole month to rebuild the CX on the front deck of our boat (more crowds), though only 20 minutes to get it running. (And only four months of riding for the parts to stop dropping off--all those bolts I forgot to tighten properly!)

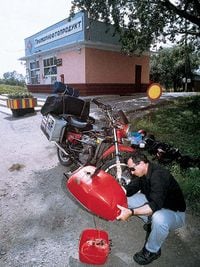

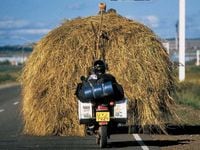

From Florida we traveled across North America to Vancouver, Canada, crossed to Japan with the arrival of spring, 1999, then headed by ferry to Vladivostok at the far eastern end of Russia. During the short Russian summer, we rode a third of the way around the globe: through the Siberian forests and, finally, back to Europe. We had traveled around the world twice.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)