It all happened very quickly.

It was autumn 1980, and Yamaha had just launched a load of all-new '81 spec bikes, including its Virago—Japan's very first V-twin custom. The Virago's appearance at Yamaha's annual dealer meeting broke an unspoken (at least to outsiders) agreement among the Japanese manufacturers to not build a V-twin custom. But there was an added bit of controversy: During the announcement, Yamaha's president reported that Yamaha had not only taken over the number-one sales position in Europe (factually true), but it would shortly do so in the US as well. Whoa!

As America's perennial motorcycle sales leader, Honda was both shocked and embarrassed by this bold claim, and feelings at Honda HQ in Tokyo and the R&D works at Asaka quickly turned ugly; calling out a competitor publicly is patently un-Japanese. But those in the know at Honda and elsewhere realized that the company had gone a bit soft in the two-wheeled sector during the late 1970s as it concentrated on cars. This very public loss of face made upper management, including Soichiro Honda himself, not at all happy, and the Big Boss, although no longer involved in day-to-day management, had a word with Shoichiro Irimajiri, the father of Honda's exotic GP racers of the 1960s and, more recently, the 24-valve CBX.

Iri quickly put a development team together and within two months had a plan for several all-new V-twins for ’82 and ’83—customs, standards, and sportier bikes. These were shown in sketch form to various R&D teams around the world, and soon all agreed to move ahead. But only weeks later the teams got a stunning message from Japan: The V-twins had been scrapped, and a new direction would soon be announced. The guts of that new plan? An entirely new line of V-4s, one of which would be a pure racer replica.

“We were shocked,”American Honda Product Planning Manager Jon Row remembers. “People at the highest levels decided that V-twins, no matter how innovative and stylish, would be seen as just matching or countering Yamaha. And that was not acceptable. Our product-planning group, Bob Doornbos, myself, and Dirk Vandenberg, were amazed when they announced the V-4s. We simply didn’t believe they could be designed and built in a year’s time. But then R&D told us that Honda management had informed the unions that a state of war existed with Yamaha and that there would be concessions regarding overtime, et cetera, to make it happen.”

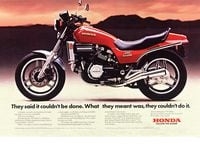

It was as much a matter of pride as a business decision. “The company very much wanted to distinguish itself at that point,” Row says, “and V-4s were to be Honda’s thing. They were expensive and much more difficult to produce. But Honda felt up the task. It was almost a challenge: ‘Think we can’t do it? Watch this!’ It was right up their alley.”

Honda’s new V-4-powered lineup would begin with the Magna and Sabre models, introduced for 1982. They were shockingly advanced, featuring all-new, liquid-cooled V-4 engines, and they’d be drawn, designed, prototyped, and built in just a year—an unheard of thing when new bikes typically took 18 to 24 months to morph from sketch to production. And while the bikes were expected to be popular and sell well, it was the sportbike planned for 1983 that would best exemplify Honda’s newfound engineering dominance, just as the CBX had attempted—and only partially succeeded—to do a few years earlier.

Isao Yamanaka, large project leader (LPL) for the V-4 project (and who spearheaded the CB750F and CB1100R projects earlier) remembers those years well. “We had to keep the number-one position,” he says, “so everyone worked extra hard. We chose the V-4 for its character and originality, as other manufacturers were building inline engines. We wanted to be different.” The order of the projects was determined at the outset. “We began with the Magna and Sabre,” he adds, “because we felt the more general and cruiser style was more important to sales in the US market at the time.”

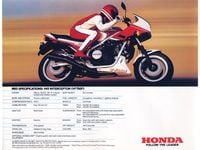

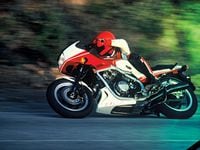

The sportbike, internally known as the RC15, was eventually called the V45 Interceptor. “For the Interceptor,” Yamanaka says, “our goals were to build the best-performing sportbike available anywhere, which is why we used so much racing technology: perimeter frame, liquid-cooled V-4, 16-inch front wheel, et cetera,” Yamanaka doesn’t mention Honda’s brutally fast, V-4-powered, liquid-cooled, and spar-framed FWS Formula One racebike or the roots of Honda’s foray into multi-cylinder vees—the oval-piston NR500 of ’79 to ’82—and its legendary engineering father, Takeo Fukui. But they absolutely affected how the Interceptor concept was approached by engineers.

American Honda’s Mike Spencer got involved with the Interceptor project immediately after joining Honda’s product-testing team in early 1982 after his AMA Superbike career ended. “I first saw the Interceptor during my initial trip to Japan,” the ex-Honda Superbike pilot says. “We tested V45 prototypes in two guises, one with a small cockpit fairing and another with the half-fairing the bike ended up with. There were big discussions about which fairing to use. Quarter fairings were big at the time, Kawasaki’s GPzs and Suzuki’s GS1000S being the best examples. Some felt the larger fairing was too extreme for the day. Others felt strongly [the larger fairing] was the coming thing and that buyers would embrace the racier look. In the end they picked the right one. Much [of the decision] had to do with function. The handling of the half-fairing bike was night-and-day better than the cockpit-fairing version. Whether it was extra stability up front, or extra weight, or aerodynamics, it clearly made a big difference at speed.”

Appearances are one thing, but Honda needed the new V-4 sportbike to have a great engine, one to make fans forget about Honda’s iconic inline-fours. “The goal for the engine was twofold,” Spencer adds. “Make more power than any other 750, and make it more usable too. I didn’t care for the drone of the 360-degree crank layout; the 180-degree setup on the VFRs had a much sweeter sound. But the [V45] was so much better than anything else at the time.” That “drone” was the result of Honda’s decision to have the pistons in each bank rise and fall together. Think of this layout as a pair of 90-degree V-twins joined side by side. This crank orientation partially simplified intake and exhaust tuning, though when Honda developed the VFR (introduced in ’86) and power was the main goal, it changed to a 180-degree crank design and the now-mythical geared cam drive.

Honda would not just break new ground on the engine side, but it would do so throughout the chassis. Again, Spencer: “The 16-inch front wheel, which we’d used on our Superbikes in ’82, was like power steering. Nineteens and 18s couldn’t compete functionally or aesthetically. Having a 16 made the bike look so serious. The Sabres and Magnas had some handling challenges during development, but the Interceptor basically had none. They were night and day. The perimeter frame wrapped around the narrow engine and was as light as anything at the time. It was steel, yeah, but a good design. The Pro-Link suspension, the anti-dive fork… There was a ton of technology on that thing. There wasn’t tons to do on the development side either. They got it right early on, and we just refined it.”

After years of primarily alphanumeric bike names, the Interceptor moniker was a bit of a change. “I came up with it,” Row says, “as I’d always loved it after hearing gas pump jockeys talk about Ford’s police cars with ‘Interceptor’ engines in the ’60s. Kawasaki had an Interceptor snowmobile at one point, but when they got out of snowmobiles [the name] became available and we grabbed it. I had become American Honda’s ‘name guy’ in those days and recommended using a cubic-inch designation to further distinguish the V-4s—thus the ‘V45’ thing.”

The Interceptor debuted in late ’82 at Honda’s dealer meeting, and although it created a buzz, response was tempered somewhat by the crush of all-new bikes announced that evening. “1983 was the year of the V65 Magna, and it sort of stole the show,” Row says. “Remember, ’83 was the heroin high point for new model releases, and dealers were like junkies. I doubt most were able to fathom the significance of the Interceptor since there were so many other new models diverting their attention—16 all-new bikes and 56 in the lineup total! The Interceptor and big-bore Magna, CB1100F, 750 and 500 Shadows, 650 Turbo, GL650 Interstate, new Nighthawk 650 and 550s, V-twin Ascot, XR350, more new CRs, upgraded ATVs, and more… It was unreal.” Yamaha had very definitely awoken a sleeping giant.

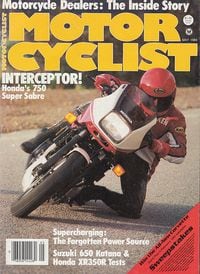

If dealers lacked some enthusiasm for the Interceptor, sportbike-loving magazine editors more than made up for the deficit, featuring it on their winter-edition covers and again in early summer editions once testbikes arrived. The road test reports were hugely positive, with staffers writing glowingly of the VF’s technical credentials and highly functional abilities.

"The Interceptor can do it all," Cycle wrote in its May 1983 issue. "As a sport bike it's nearly perfect—always there, more than ready, anticipating your every move. When it's time for hard charging the VF750F excels…But [the Interceptor] is not a narrow purpose machine…the riding position is one of the best available, vibration is well controlled, and a wide range of suspension adjustability allows for a surprisingly comfortable freeway or sporting ride."

Motorcyclist and Cycle Guide proclaimed the Interceptor the Motorcycle of the Year, with Cycle Guide actually chroming an example for its cover photo. And the VF won Cycle World's 750-class shootout. It was the quickest, fastest, and most powerful of the 750s. In our June 1983 issue, we pitted it against the then-new Suzuki GS750ES and the Kawasaki GPz750, still an air-cooled, two-valve engine. The Honda put down an 11.69-second/114.5-mph run, beating the 27-pound-lighter Suzuki by a mere six-hundredths of a second but the aging Kawasaki by a heady six-tenths. We said, "The Interceptor is powered by the best 750cc street engine ever built."

Not all was hunky-dory, however. The VF was, at 550 pounds full of fuel, some 20 pounds heavier than Kawasaki’s GPz750 and nearly 30 more than Suzuki’s GS750. It also delivered a somewhat vague, disconnected feel during aggressive riding. But the biggest problem, and one that nearly beheaded the entire V-4 project, was premature camshaft wear brought on by mismatched cam-bearing surfaces and tolerances exacerbated by not enough oil flow to the cam boxes. The problem affected Sabres and Magnas at first, and Honda wasn’t able to fix the problem before Interceptors began rolling off the lines. Things were especially bad in Europe, where bikes are typically ridden much more often—and at higher speeds for longer periods—than in the US.

Despite all this, the Interceptor sold out quickly on a wholesale level and performed extremely well in showrooms. A huge print and TV advertising budget helped, as did racing, with Freddie Spencer, Mike Baldwin, and David Aldana sweeping the top three spots at Daytona in that year’s opening AMA Superbike event. HRC-prepped V45s scored more victories during the ’83 season. And while Wayne Rainey and Rob Muzzy grabbed the ’83 Superbike title on a well-developed air-cooled GPz750, the Interceptor-based Superbikes were the center of attention in the paddock.

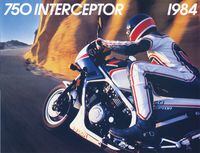

Interceptor momentum carried into ’84 with 500 and 1,000cc versions, both of which helped expand Honda’s presence in the sportbike market. But Honda wouldn’t have the high-tech sportbike playground to itself for long. Kawasaki introduced the Ninja 900 in ’84, Yamaha dropped the five-valve FZ750 bomb in ’85, as Suzuki unleashed the GSX-R750 into Europe and Asia that year. (America finally received the GSX-R in ’86, along with the fearsome GSX-R1100.) Honda responded with the aluminum-framed VFR750 in ’86, but by then the momentum had started to shift. Not until the 1993 CBR900RR would Honda again build the hardest-hitting supersport in the land.

Still, Honda got there first. First with perimeter frames, first with liquid-cooling, and first with 16-inch front wheels—and all in the same year. It’s not hard to argue that the V45 marked a critical turning point in sportbike development. Previously, sportbikes were slightly updated versions of street standards—truly, a GPz was not a lot different than a run-of-the-mill KZ, a concept that held for all the Japanese manufacturers. But the V45 was different from the Sabre in concept and execution, in a thousand ways big and small, and in doing so it not only showed Honda’s engineering might but without question helped usher in what would be three decades of intense supersport development among the Japanese manufacturers. A war started by Yamaha but quickly escalated by an emboldened Honda. Very, very quickly.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FZXHNOQRNVA3BIDWAF46TSX6I4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JRSFLB2645FVNOQAZCKC5LNJY4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ITNLTIU5QZARHO733XP4EBTNVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)