So there you were in 1972, laying low, dodging the draft, tie-dyeing the cat, grooving to your Rod McEwen records, rebelling and protesting but most assuredly not inhaling. You thought that Honda's awesome 750 Four, a bike that had come out the same year man landed on the moon, was about as advanced as motorcycles could get, and then....

Oh what's the use?! I can't write this story--heck, I was only 13 years old, and thought my brother's Bronco 50 was the height of trickness. In those days, the main concern, frankly, was, er, satisfaction. I couldn't get no, probably because I was about 4-foot-2 and 39 pounds with acne and a stutter. (Really, I haven't changed much.) I had about as much chance of getting my grubby paws on a shiny new Z1 as I did of getting my grubby paws on Tracy Coleman the prom queen, which is not to say that certain fantasies weren't entertained about both. All right, I'm lying. Z1 Kawasakis never entered my imagination until a while later.

Meanwhile, Kawasaki was selling the things--at $1895 a copy--like your proverbial hotcakes. The factory cranked the first Z1s out at the rate of 1500 per month, while it gauged the buying public's reaction (already gauged a few years earlier by Honda's 750 and found to be !$!$!). By 1975, Z1B's were being extruded at the rate of 5000 per month.

Why the Z1 was so popular is a question easily answered by looking at its competition--there really wasn't any. Honda's CB750 was the first mass-produced four-cylinder for the masses, but its styling, restrained to begin with, was long-of-tooth by 1973. (Other "open-classers" that year included such dismal relics as the Yamaha TX750 and Triumph Trident.) The Z1, in comparison, was swoopy, stealthy, waspy--check that ducktail rear end, the tank shape, chrome fenders and blacked-out engine. Like Tracy Coleman, it was a simple case of proportion. Everybody's got the same parts; how they're put together makes all the difference.

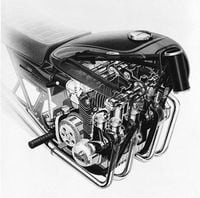

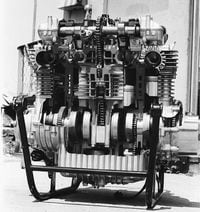

Having gotten over the initial shock, it was time to delve into the beauty within. You'll note that there are two cams up there--two. (Say, what's a cam?) And look how big it is! 900! Hooo! That's the biggest dang monster. The driveway basketball game always screeched to a halt when Big Kev's Z1 burbled past. Apparently we were looking at the world's first superbike.

By now you must've already heard the story of how the Z1--code-named "New York Steak" for some ridiculous reason or other by Kawasaki--was originally intended to be a 750, and of how Kawasaki brass nearly suffered a corporate coronary when Honda introduced its own 750cc four-cylinder in late 1968. Kawasaki, cornered, had no choice but to make the Z1 even bigger and stronger and tricker than the mighty CB750.

So the Z would have double overhead cams, and they would transmit their meaty motion directly to the valve stems without interference from rockers or pushrods--the way God intended, dangit--and yes, at a nicely square 66 x 66mm, it would displace 903 cubic centimeters.

Inklings of what was to come arrived at Motorcyclist in early 1972, when Editor Bob Greene put down his coffee cup and traveled to Japan to put cheek to seat for the first time, in the tight confines of Kawasaki's dragstrip/testing area, filing this report:

"Weeks of anticipation exploded with a violent twist of the throttle grip as each rider's turn came up, redlining the silky four in gears one through five. Some saw 100, some 110, one 120 mph before the rapidly closing wire fence at the end of the strip occasioned the near-full use of both brakes. An occasional chirp of rubber told that one of the more hungry pressmen had almost overcooked the Steak as he reluctantly backed off the big burner...."

Test units were dispatched to the U.S. in early 1972, here to be flogged by a team of grizzled American Kawasaki employees led by one Bryon Farnsworth. Three Z1s were hammered for 5000 miles around Willow Springs and Talladega Raceways. Willow, nothing then but a track with barbed wire around it, was the first venue.

"Bill Huth [Willow's owner since forever] said he'd stand guard and make sure nobody drove across the track," Farnsworth recalls.

"Talladega was prone to having those heavy thundershowers," he added. "We were down there testing with Gary Nixon, Hurley Wilvert, Paul Smart, some fast Texas guy whose name I can't remember, and three or four hot Japanese riders. [Yvon DuHamel and Art Baumann were there as well.]

"What we were trying to do was just hold the thing wide open through a whole tank of gas. If you could just hold it wide open, you could run right up there against the wall, doing about 140. It'd wobble some, but if you just kept the gas on, it was OK.

"So I sent out one of the Japanese guys. It started to rain one of those big rains, and he pulls in. I was in charge of testing, so I walked over to him to ask, 'What the hell are you doing?'

"'It's raining,'" he says, "'too dangerous.'"

"Bullshit, I said, and jumped on the bike myself. I scared the absolute hell out of myself that day next to that wall. In the rain, it was really dodgy.

"Still, for the amount of power [the engineers] shoehorned into what was really basically an H-1 frame, the thing worked pretty well. I mean, you could feel the head moving in relation to the swingarm pivot whenever you twisted the throttle, but it all worked. Frames then were pretty much all the same; here's where the engine goes, and there's a place for the seat and gas tank," says Farnsworth.

Phase Two of Farnsworth's test consisted of an 8000-mile L.A.-to-Daytona-and-back flog, the same bikes cleverly disguised in Honda CB750 fuel tanks and badges to avoid detection. One young guy in Shreveport, Louisiana, was the only one to see through the Honda facade in the entire journey; "What the hell izzat? That ain't no Honda."

Rear tires were roasted at 6000 miles, and drive chains at half that. Otherwise, everything appeared ready for prime time after teardown back at Kawasaki HQ in California.

Dealers sold out of Z1s immediately, so quickly that Kawasaki employees couldn't even get a Z through the employee discount deal. Aftermarket performance suppliers who'd gotten involved with the CB750 Honda went completely ballistic in cranking out pipes, cams, carburetors, wheels and brakes for the Z1. Those parts encouraged people to ride fast, take lots of chances, and to race. Those races encouraged the competition (after it rocked back off its heels a few years later) to build things like Yamaha XS Elevens, Suzuki GS1000s, Honda CBXs and war that continues to this very day.

The Z1, though, had already exceeded the ex-pectations of its conceivers. From 1973 on, the name "Kawasaki" would no longer be associated with loud, smoky and pipey two-stroke triples, but with big, brutal, powerful--and most important, refined--four-stroke motorcycles.

Kawasaki Z1: Charting the Changes

The Genesis of the Mighty Z**

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)