In the first part of Gasoline 101 (see Part One here), we embarked on a journey down the hydrocarbon highway, exploring the origin of gasoline , examining gas quality and additive packages, and talking about octane and detonation. Now we'll circle back to a fuel additive that we breezed over last month but that warrants further scrutiny: ethanol.

Ethyl alcohol, or ethanol, is a grain alcohol that in the US is derived from corn. America is the world’s largest producer of ethanol (Brazil is the second), but despite our thirst for beer, most of that alcohol is going into our gas tanks, not down our gullets. Why is it in our gas? According to Congress and the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), corn juice is blended into our gasoline to reduce our dependence on foreign oil and to help cut tailpipe emissions. The politics, economics, and environmental impact of ethanol are all subject to debate, but we’ll steer clear of that controversy and instead stick to the facts and focus on how ethanol affects your motorcycle and thus you.

Ethanol’s role in gasoline is that of a biofuel filler, an octane booster (pure ethanol has an octane rating of 130), and as an oxygenate. Oxygenates are compounds that contain oxygen in their chemical structures and contribute it to the combustion process, in essence leaning out the mixture as it burns. Oxygenates help eliminate unburned hydrocarbons by, well, helping them burn. Along with that comes increased exhaust-gas temps and thus stress on the exhaust system. Engines burning blended fuel will also be slightly less efficient because alcohol is only about 66 percent as energy dense as gasoline.

Nearly all of the gasoline sold in the US contains up to 10 percent ethanol by volume and is referred to as E10. E10 has been around since the mid-2000s and is approved by the EPA for use in all vehicles. For the most part E10 works fine as a fuel, but it’s known to cause problems for the fuel systems on older bikes and also complicates long-term storage. Ethanol is a corrosive liquid and can damage parts not meant to come in contact with it, causing hoses and gaskets to swell, deteriorate, and distort. You might recall the rash of warped plastic gas tanks on Ducatis and Aprilias in the mid-2000s—ethanol was to blame. For the most part manufacturers have adapted and now use ethanol-resistant fuel-system components, but older bikes (pre-2000) that were never designed to flow blended gas are susceptible to issues. If you ride an older bike, check out the “Learning To Cope With Ethanol” sidebar to see how you can combat alcohol-induced fuel-system failure.

Even if your bike is equipped to cope with ethanol, blended gasoline may still cause complications when the kickstand is down for long periods of time like it is during the winter. That’s because ethanol is hydrophilic, meaning it attracts and binds to water, including water vapor in the air.

“When the ethanol absorbs enough water,” says Helix Racing Products’ Benson Greer, “it falls out of suspension and sinks to the bottom of the tank. This is called ‘phase separation,’ and it can begin to happen in as little as 30 days.” And since ethanol is a primary octane ingredient and is now bound to water at the bottom of your tank, “the gas that’s left may have an octane rating that could be in the low 80s,” Greer says.

Preventing phase separation—as well as delaying oxidation, the chemical process responsible for making gas go stale—is one of the things modern fuel stabilizers like Helix’s 5-in-1 Ultimate Fuel Stabilizer are designed to do. If you plan on storing your bike for a month or more, make sure to mix in a quality fuel stabilizer and fill your tank completely to reduce the volume of air and thus water vapor present in the tank.

Increased engine heat, reduced mileage, fuel-system corrosion, and a shorter shelf life are the direct problems motorcyclists face with today’s ubiquitous E10, so it’s easy to understand why the introduction of E15, a 15-percent ethanol/85-percent gasoline blend, is cause for further concern. E15 is currently available at about 80 stations in 12 states, with efforts underway to make it available nationwide. There is also a lot of effort going toward halting E15’s spread, at least for the time being.

Leading the charge against E15 is the AMA (American Motorcyclist Association). Pete terHorst, a spokesperson for the AMA, says that “the AMA doesn’t oppose E10 or ethanol as a fuel additive in principle, but we believe the EPA has rushed E15 into the marketplace without studying its potential to damage engines. The EPA has also failed to adopt adequate measures to ensure that fuel purchasers do not inadvertently fuel with E15.”

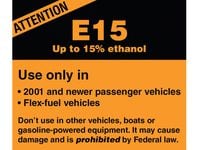

No manufacturer has stated that its motorcycles can safely use E15, and most owner’s manuals state that doing so will void the warranty. In recognition of this fact, the EPA responded by publishing a list of vehicles—including motorcycles—not approved to use E15, even going so far as to say fueling a motorcycle with E15 is illegal.

The problem is, little is being done to educate consumers or inform them that they are at a pump that dispenses E15. E85, an 85-percent alcohol blend known as “flex fuel” that is available nationwide, is clearly marked with a separate, yellow handle (just like diesel pumps have a green handle). Pumps that dispense E15 on the other hand are only distinguished by a small decal on the pump facade that’s easily overlooked in the collage of notices, warnings, and labels found on most gas pumps. “The opportunity for inadvertent misfueling is high, given the confusing labeling,” says terHorst, which is why the AMA is pushing to halt the sale of E15 until further studies are conducted.

For more information on E15, visit americanmotorcyclist.com, and in the meantime, steer clear of pumps displaying the black-and-yellow E15 label.

We’ve received numerous letters about it in the past, and it’s a hot topic on car and motorcycle forums—how much regular (or E15, for that matter) gasoline are you putting in your tank if you select premium but the previous customer bought the cheap stuff? And is it enough to dilute your purchase?

The gasoline retailers we spoke with didn’t have an answer, so we turned to one of the nation’s largest gas-pump manufacturers, Bennett Pump Company, for more information.

The engineer we spoke with explained that pipes for all three grades of gasoline feed into a manifold at the top of the dispenser, right where the hose exits the unit. The typical hose length is 10 feet, though some models use a 12-foot or even a 15-foot tube. The industry standard for the inner diameter of that hose (whether it’s in a coaxial vapor-recovery setup or a plain pipe) is 5⁄8 of an inch. A little number crunching yields a volume of 304.8cc for a 10-foot hose, which works out to 0.16 gallon. That volume rises to 0.19 gallon for a 12-foot hose and to nearly a quarter of a gallon for a 15-footer.

Assuming your bike’s capacity is 4 gallons, the 15-foot hose’s 0.24-gallon volume is only 6 percent of the tank’s capacity. For the more common 10-foot hose it’s just 4 percent—in other words, negligible. And that’s assuming the hose is completely full from the manifold to the nozzle valve, which it may not be. Our advice? Forget about it.

If you ride an older (pre-2000) bike, the ethanol in today's gasoline may well cause you trouble. You can cope by replacing or upgrading your fuel-system components with ethanol-resistant parts. Helix (helixracingproducts.com) and Motion Pro (motionpro.com) sell ethanol-resistant fuel hose, and more gaskets and seals are being offered in nitrile and Viton, both of which withstand ethanol just fine.

If you can’t find aftermarket chemical-resistant alternatives for your bike, your best bet is to replace your old parts with new OEM components. They might not be designed for E10 gas, but fresh parts have a lot more fight in them than old ones, and it’s not like the parts will disintegrate overnight.

If you want to avoid ethanol entirely, some places still sell E0 (pure gasoline), though such stations are few and far between. Another option is VP's T4 fuel, sold in 5-gallon pails and 54-gallon drums through vpracingfuels.com. T4 is 100-octane, unleaded, and ethanol free, but it's also more than $10 a gallon and not technically legal for road use.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IM2PKPX3LSQJGMYVCTGDY5MTKQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)