Tuesday, March 7, 1995

"Son of a bitch!"

The words boomed from within Garage 21 like a reverse-cone megaphone at full honk.

Even without the profanity, I knew something was wrong. The movements of the garage inhabitants were too frantic, the air too thick with tension.

I was sitting in the back of Todd Henning's crusty Dodge van in my leathers, sweating, waiting to head out for some badly needed practice on the Drixton-framed 450 Honda vintage racer our crew had built specifically for AHRMA's 1995 season opener at Daytona--and on which they were now working feverishly. The upcoming 15-minute session was the last practice of the day, the final chance to ride the bike before my race, the Premier 500 event, which was to be flagged off in less than two hours.But the bike wasn't cooperating. Something had gone way wrong.

I needed this practice so bad it hurt. Since we'd arrived four days earlier, I'd gotten barely five laps on the bike. It was brand new (or as new as a 20-plus-year-old motorcycle can be), and we'd been plagued by a long list of teething problems. If we missed this session, I'd be climbing aboard and racing a motorcycle I knew next to nothing about. This did not make me happy.

Henning came out of the garage 30 seconds later, his head down, and I knew we were screwed. "We're not gonna make this practice, are we?" I asked, already knowing the answer, the bile of frustration boiling in my gut."Nope," he said, looking up, "we're not. The cam chain jumped a tooth when we replaced the rocker spindles; the valves are hittin' the pistons. We've got to re-time it."

Here I was, my first race in four years, in what was arguably the most visible and important vintage event of the season, in vintage roadracing's most prestigious class, on a bike with race-winning potential--and I'd be racing with just five laps of practice.This time it was I who swore.Frankly, I hadn't expected this much trouble, this much gut-burning frustration. I'd expected to basically show up and ride, just as Jack Seaver had said when he'd proposed this hairball scheme over the phone three months earlier.

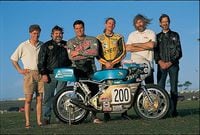

Seaver had said that he, good friend Patrick Bodden and vintage champion Todd Henning would build a Drixton-framed 450 Honda for me to ride at Daytona. The bike would be identical to the machine Henning had used earlier that year at Daytona to lay waste to AHRMA's 500 Premier field. All I'd have to do was show up and ride. Was I interested? And would I write a story about it?

An outrageous plan, but one with definite appeal. For one thing, I hadn't roadraced in four years, and I missed it. I'd raced motorcycles on and off since '74, and the sights, sounds, smells and adrenaline rush of racing had somehow fused with my genetic makeup. Here was an ideal way to literally get back in the saddle. Plus, how tough could vintage competition be? Certainly not as nasty as the slam-fest production racing I'd done over the last decade.Yeah, I told Seaver, let's do it.So we dug in and went to work, me soliciting support from various aftermarket companies, Seaver and Bodden beginning to piece together the chassis kit (supplied by Henning) in Bodden's Alexandria, Virginia, workshop.

Out on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where he lives and works, Henning began building the additional engine we'd need, using the same basic parts and porting recipe he'd used to win Daytona earlier that year on his own Drixton. Countless hours in his shop and on the ACS Racing dyno had netted him over 60 rear-wheel horsepower, an astounding amount for an engine capable of just 35 ponies in stock form.

Unfortunately, it would be weeks before the first non-kit bits began arriving at Bodden's home. The project was eating time, a commodity he--or any of us--had little of. By the time all the parts had arrived, less than a week remained before he and Seaver were due in Daytona. Those final few days, some of which turned into all-nighters, were nightmarish for both men.

As hard as they thrashed, Bodden and Seaver ended up leaving a day late. Worse, the Drixton still wasn't ready. Several components--such as the exhaust, front brake and bodywork--had yet to be worked out. This was typical Bike Week stuff, Daytona turning into the time/space black hole (familiar to most who've raced there) that sucks up every available moment, leaving everyone stressed-out, pissed-off and ugly.The thrash continued once we'd all convened in garage No. 21 on Saturday morning, March 4. We'd planned to use two of the day's AMA/CCS races as practice, but with our Drixton not yet ready, we spent all day Saturday and Sunday buried in the garage.

And what a twisted show developed there--how bizarre it all must have appeared to anyone peering into that plywood cave over the following days. Half a dozen vintage racebikes, all in various states of (dis)repair: yanked-apart engines sitting on the bench; Bodden's lathe--yes, lathe!--spinning constantly; rags, safety wire, tools and other race-waste strewn about the floor; bleary-eyed friends and crew members sleepwalking through the rubble; hope and despair trading places on the hour.

By late Sunday morning I'd still not been on the bike. Going into this whole adventure, I'd hoped the bike wouldn't have too many bugs to work out. But racebikes are finicky things, just-built racers being even more so. The fact that our Drixton had teething problems wasn't nearly as much of a problem as the lack of time we had to work them out.

Henning, knowing I'd need a straightjacket if I didn't get on track at least once before the AHRMA events began the following day (Monday, March 6), put me on his personal Drixton for the final CCS practice, where I logged four laps. It helped; I finally got a glimpse of what I'd be dealing with in two day's time.

To try to ready the bike for day one of AHRMA's two-day vintage-fest, Bodden, Seaver and friend R.L. Brooks pulled an all-nighter at the AMI campus Sunday night. It paid off, because on Monday morning the gorgeous aqua and gold No. 200 Drixton Honda finally breathed its first air. It ran--we'd finally get some practice!

A little, anyway. Our first session lasted just three laps, ending when a valve adjuster locknut came loose from the bike's intense vibration. And that wasn't all: the four-shoe Fontana front brake, trick as it was, needed far more than three warm-up laps to seat before it would work properly. The front tire had munched the leading edge of the lower cowl, too, blasting a huge chunk of fiberglass from the lower fairing under braking. The second session was no better. The adjuster nut came loose again, and we got just one lap. We'd have to figure things out that night, because we had only one practice remaining the following morning.

That evening we fixed the fairing, changed rocker spindles (which had caused the adjuster problems) and wired the adjuster nuts. But as we slapped everything together early Tuesday morning, hurrying to get the bike ready for our final session, Henning discovered that the cam chain had jumped a tooth, and that the valves were contacting the pistons.We'd missed our last practice. We'd hit bottom.

Luckily, the good folks at AHRMA helped us off the floor a bit by allowing us to run the bike in the Formula 500 event, which was one hour before 500 Premier. We'd use the laps as practice. On the warm-up lap, the bike seemed strong, and the suspension changes Jim Lindemann had made (educated guesses, mostly) seemed in the ballpark. I got a good start from the back row only to come to a stop halfway through lap one when the shift lever broke at its weld point.Still, there was good news. The bike had run strong, and the chassis, at least during my fast half lap, seemed fairly well dialed. And, we all agreed, it was far better to discover the weak weld now rather than later.

With a half-hour to go before the 500 Premier pre-grid, the questions began swirling: Would the bike last eight laps? Or would it let us down after all we'd gone through? I knew the bike was competitive, though we simply had to get through these teething problems. The crew was exasperated and tired. It'd be a miracle if it went the distance, I remember telling Henning--a major miracle.

With no previous AHRMA points, I was gridded on row 12, the last row, about 50th. I could see Henning up front in row two, 150 yards ahead, with the Barber Racing G50s nearby.

The butterflies in my stomach were in full force, but I got a good start, the bike launching ferociously, the bikes directly ahead blurring past me. Lap one was a slam-fest, pure berserko; I probably passed 10 bikes in turn one, five in turn two, maybe 10 to 15 more by the time we hit the banking. By the time we ripped into the chicane on lap one, I was fifth, and three laps later, after passing Kurt Liebmann (also Drixton Honda-mounted), I was third. But by then, Henning was way out front.

Those first few laps were practice, really; I was getting to know the bike, how it stopped, turned, accelerated and behaved at speed. Sticky Avons and plenty of cornering clearance helped me slice big chunks off my lap times each time around. The Drixton was light, flickable, roomy and surprisingly fast--great fun to ride.

By the fifth lap, I began closing on Barber Racing's Chuck Huneycutt, who was second aboard a hellishly fast G50. By lap six, I was all over him, and shocked to find that we'd closed dramatically on Henning, who was having trouble with lappers. I finally made the pass for second entering turn four, though Huneycutt used the speed of his G50 to draft back by me a lap later on the back straight. But we were right there.

With a lap to go, the three of us were nose to tail as we shrieked past the white flag. Did I actually have a shot at this thing? I closed the gap further through turns one, two and three, and once again went underneath Huneycutt for second in the West Horseshoe. I bungled the drive out, though, which allowed Huneycutt to pull even as we dragraced to turn five, the all-important left-hander that led to the banking.

I remember strategizing at that point. I could be patient and go for the draft--and maybe the win--on the final straight (a common Daytona win tactic), or I could maybe zap Huneycutt here in turn five, screw up his momentum, and try to put a bit of distance between us so the superior power of his G50 wouldn't be enough to get back by me at the finish.

I went for the pass, knowing he had a little motor on me and not sure I could draft him (and maybe Henning) at the finish, certain I'd be able to outbrake him with a Butcheresque late-brake maneuver entering five. But he hung in there (damn him!), and more important, he had the inside line, a vital point I hadn't considered in the heat of battle. We hit the brakes simultaneously, both of us chattering and skidding toward the mouth of turn five.

But he had me--I knew it the instant we apexed. And just as I'd have done, Huneycutt took me wide, forcing me to either back off (handing second--or the win--to him on a platter) or end up on the grass, flattracking. Not willing to back off, I did the latter, which killed any chance of me winning or even making it close. Henning won, beating Huneycutt to the flag by half a wheel.

The cool-down lap was epic--fans and corner workers standing and waving and yelling, a high-five from Henning, the drug-like, endorphin-based rush of a maximum, mind-burning effort, the proud, jumbo smile on Patrick Bodden's face--and the faces of our entire crew--as I coasted into pit lane for an interview--an interview!--with track announcer Richard Chambers.I'd raced for 20 years, but never had I felt as good as I did at that moment.

At post-race tech, AHRMA officials spent minutes trying to extract fuel (for testing) from my Drixton's tank. Later, we figured I had maybe--maybe--six ounces left. That extra splash Jake had put in as we left the garage an hour before had kept us alive. And that bolt Patrick had installed on the brake-lever pivot just in case the clip fell off? Well, the clip had fallen off. Two more miracles; someone upstairs was definitely smiling upon us that afternoon.

Daytona '95 was a tiring, exasperating grind, for sure. But it was also one of the most intense--and satisfying--weeks of my life. Looking back now from four weeks time, I'd do it all over again in a minute. Only this time I'd make Jack Seaver promise to start earlier. You know how Daytona is.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)