Seventeen years ago, Motorcyclist staff did a stupid thing. We drank gallons of malt liquor and then climbed onto--and fell off of--a motorcycle. Why? To examine just how alcohol affects the ability of riders to ride. Or their ability to choose not to ride. Since then, a lot of ethanol has flowed into motorcyclists, a lot of whom have wound up dead.

Motorcycle fatalities have been steadily rising since 1997, when 2116 riders expired. In '03, the number was a sobering 3592. That's more people than were killed on September 11, '01. And it represents a whopping 70 percent increase in just seven years.

Alcohol-related fatalities, as one might expect, have risen commensurately. In fact, 45 percent of the riders killed in single-vehicle crashes in '02 had been drinking. And a staggering 36 percent of those riders were staggering drunk, with a blood alcohol level of 0.10 or higher.

On weekend nights, the time one would expect to find more drinking riders, the numbers are even worse: In '02, 62 percent of motorcyclist fatalities on Friday and Saturday nights involved alcohol.

Why are motorcycle fatalities increasing? Well, nobody knows because nobody has funded a real, comprehensive study of motorcycle accidents since the Hurt Report way back in '81.

Our guess is the nature of motorcycling, and motorcyclists, is changing. Back in '81, the average age of a motorcyclist involved in an accident was 24. Now, it's 38. And the cruiser market, which was just getting started in the early '80s, has been exploding for years. What do older guys--many of them new to motorcycling--on cruisers tend to do? Generally, they don't tour, they don't carve canyons. Instead, they all too often ride to a bar, have a few with their buddies and ride home. Which might mean more guys are riding and drinking more.

Drinking and riding is a huge problem, just as it was in '87, when we concocted the story that would let four of us drink ourselves into oblivion and into motorcycle journalism history.

We thought about remaking the story. But we quickly realized we had no desire to repeat the crashing, vomiting and hangovers. Been there, barfed that. Some things, we came to understand, are just too perfector too stupidto repeat. So we decided to rerun the piece with comments added by the participants/victims lending the perspective of their accumulated wisdom in the intervening years.

GETTING HAMMERED, 1987

This isn't news, but the cascade of accident statistics we see every year tells us it bears repeating: Drinking and riding motorcycles is a very popular way to kill yourself. Nearly half the fatalities in the famous Hurt Report (the University of Southern California's compilation and analysis of 900 motorcycle crashes in the Los Angeles area, published in 1981) were alcohol-relatedthat is, a large proportion of the fatally injured motorcyclists examined had enough alcohol in their systems to affect their riding performance. In a Canadian coroners' study of motorcycle fatalities, 70 percent were riding under the influence at the moment they shuffled off this mortal coil.

We know booze and bikes are a deadly combination. But apparently thousands of us drink enough to affect our riding skills and ride home anyway. Some of us make it, some of the time. Thousands don't.

Alcohol is a depressant; it tends to slow down most brain functions. But when it depresses certain parts of the brain, the effect is apparent stimulation. At very low blood-alcohol levels, inhibitions tend to fall away, so some individuals actually improve in certain performance tests. Judgment, however, deteriorates at the same time inhibitions leave, and the combination in an excitable young man on a brutally fast motorcycle is very often fatal. Many alcohol-related crashes occur with riders who are not especially drunk. They just let the alcohol replace their normal caution with euphoric enthusiasm long enough to push past their machine's performance limitsor their own.

Knowing one's personal limits is vitally important. Different states set their own legal limits of alcohol use, with levels varying from 0.05 percent BAC (Blood Alcohol Content) to 0.10 percent. Nobody is saying lower alcohol levels aren't enough to screw up your riding, but for legal purposes each state has set an arbitrary BAC level, one typically high enough to give riders or drivers with relatively small amounts of booze in their systems the benefit of the doubt. But while the law of the land might give you a break if your alcohol level is below the legal threshold, rest assured you'll get no break from the laws of medicine and physics.

According to the Hurt Report, the typical accident involving a sober rider occurs in the daytime at relatively low speed when a car violates the rider's right of way. The typical alcohol-related crash is an entirely different animal. It's much more likely to happen at night, and it's usually a single-vehicle accident. Helmet use is way down, and speeds are way up. In other words, drunk riders are most likely to wind up against a tree after running off the road in the middle of the night.

It's all very easy to say, "So don't drink and ride, stupid." The fact remains alcohol is an intrinsic part of life in the U.S., and likely to remain so. What's more, the same kinds of people who tend toward exciting sports such as motorcycling also tend toward the party experience. There's a reason certain people drink alcoholto them, it's fun. The problem, of course, is deciding where the fun stops and the danger begins.

One of the unfortunate effects of alcohol is it can convince drinkers they are not affected. The early loss of inhibition at low BAC levels often gives the drinker an exaggerated sense of well-being, one which usually causes increasingly serious performance impairment at higher BAC levels. In other words, drinkers are notoriously poor judges of how alcohol is affecting them.

In the interests of science, we decided to conduct our own carefully controlled imbibe-a-thon. We Motorcyclist staffers are not allowed to ride test motorcycles with any significant amount of alcohol in our systems. Our teetotaling editor (Art Friedman at the time), who also happens to be a private pilot, decreed we follow the FAA-standard rule of no booze within an eight-hour period before riding a company-controlled motorcycle. The rest of the riding staffers are, however, moderately enthusiastic drinkers. If there's a party in the tri-county area, you can count on Karr, Ienatsch, Boehm, Ford and occasionally Berriz to be on hand. This means the test bikes generally stay behind on Saturday nights, and our respective spouses and spousal-equivalents do a lot of driving home for us.But now we had the chance to drink till we could drink no more, and grind a poor motorcycle into the ground as we tippled our way to alcoholic nirvana.

Our preliminary investigation into the physiological effects of alcohol taught us a few important lessons. For example, up to truly heroic BAC levels, simple reaction time doesn't suffer much. Drunks are relatively capable in a basic "pull the lever when the light goes on" twitch test. But driving (and riding a motorcycle) is what's called a divided-attention task, and alcohol can markedly reduce one's ability to perform in a real-world situation. An inebriated person can do surprisingly well at one simple, focused task. But as soon as he has to quickly divvy his attention between competing chores and observations, performance goes downhill.

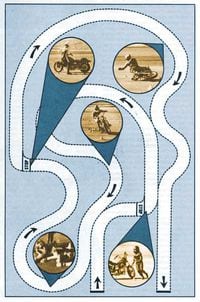

The test course we chose was a compromise between logistics, the kinds of performance we were trying to test, safety and sheer fun. Dr. Herb Moskowitz, an authority on the effects of alcohol on drivers, suggested we duplicate a complex lane-change course used in measuring alcohol-performance degradation in a '75 Swedish study. Instead, we opted to use a miniature road course designed by David Hough for use in developing basic riding skills. (Hough has been a consultant on motorcycle safety and training for the MSF, AMA and many other groups worldwide.) The simpler course didn't require the high-tech timing devices or signal lights of the Swedish study, but it did have a series of computer-designed increasing- and decreasing-radius corners and a couple of stop-and-go sections.

To make the effects of increasing alcohol level more apparent, we added a couple of off-the-bike excursions to the course. Instead of merely stopping the bike, we had riders find neutral, put the sidestand down, dismount and run once around the bike before remounting. Three out of four of our riders were experienced roadracers, street riders and drinkers. We wanted to make sure they couldn't rely entirely on their high experience levels to help them sleaze through the tests on riding talent alone. The dismounting adventures would, we hoped, break their concentration enough to make the tests more valid and comparable to real-world riders in real-world situations.

I (Ford) was elected to design the course, set it up and conduct the tests. I managed to rope Carl Spurgeon, director of licensing at the Motorcycle Safety Foundation, into helping turn the skid pad at Willow Springs Raceway into a tiny pylon-studded road course. Staffers Beer-Belly Boehm, Carlsberg Karr, Swizzle-Stick Nick Ienatsch and small, relatively inexperienced Madwoman Marcie Berriz were the designated laboratory rodents. A cooler of chilled Carlsberg Elephant malt liquor, weighing in at 5.7 percent alcohol content, was the poison of choice.

(Note to Dexter: That Elephant stuff you stocked up on at Beer Depot had a head as thick as Barbasol and packed enough pent-up high-pressure gas to trigger the bends after a couple of swigs. But maybe that was all part of your plan... -—Jeff Karr)

Because alcohol (and other drugs) affects humans in proportion to their weight, the Carlsberg dosages were adjusted to suit the participants' respective body weights. Ienatsch, at 150 pounds, was the standard-weight humanoid; he received one 12-ounce Elephant per round. Boehm, at 190 pounds, drank 1.3 bottles per round. Karr, at 160 pounds, sucked back 1.1, and Berriz, at 100 pounds, was given only 0.7 of a bottle. The four guinea pigs would now be linked in alcoholic lockstep.

We tried to eliminate the effects more practice on the course would have on the times by letting the riders run the pylons as many times as they wanted while sober. When all the riders felt they had achieved their fastest possible sober performance, the games would begin.

Hotblooded punks Boehm and Ienatsch immediately settled down to serious lapping. Ienatsch had the second-fastest time, with a 45.98, with a perfect cone-hit score of zero. Boehm, playing a little fast and loose with the four-cone slalom at the finish, turned a 45.28, with two cones sacrificed to his impatience. The poor motorcycle, a long-suffering Honda 450 Rebel, would be considerably lighter by the end of the day. Mitch and Nick were grinding metal off the pegs and pipes in long, lurid swipes as they hammered the bike from one side to the other.

Karr apparently wasn't about to indulge in an embarrassing speed contest, at least not until he was good and wasted. It took him four tries to complete a full lap without cheating; he would consistently run only halfway around the bike at the stops instead of the required full circumnavigation. Finally, on the fifth run, he logged his sober baseline time, a slightly wimpy 49.75 with all the cones still standing.

Marcie had two problems to overcome. First, at 5 feet tall, she was destined to have much more trouble stopping and running around the bike than the others. As the alcohol intake climbed, we allowed her to skip the dismounting and merely stop at each of the stop signs. Second, Marcie is a rider, not a racer, and a fairly inexperienced rider at that. She wasn't willing to push nearly as hard as the others, so her lap times were much more expressions of her confidence level than of her reflexes and coordination. Her baseline time was a 59.16, with a 100 percent cone-survival score.

The human liver metabolizes/oxidizes alcohol at the rate of approximately 0.015 percent BAC per hour, effectively removing it from the bloodstream. That means for a 50-pound person, an average drink (containing half an ounce of pure ethanol) is metabolized every 75 minutes. To make sure the riders' blood-alcohol levels stayed ahead of their metabolism curves, we started by giving them two rounds of malt liquor in succession before letting them back on the course. All the riders had eaten an average lunch before starting to drink, which has the effect of slowing alcohol absorption into the bloodstream. Carlsberg malt liquor contains 5.7 percent alcohol, about 50 percent more than most beers; accounting for delays in alcohol absorption and a small amount of liver metabolism, the research rodents did their next runs with an average BAC of 0.035 percent, or about a third of the way to legally drunk in California [in 1987—today you would be halfway to a DUI].

ROUNDS 1 and 2: 0.035 percent BAC

Nick has trouble getting the Rebel back into gear after the first stop-and-run. The engine revs wildly, and he almost tips the bike over as he attempts to slam the transmission into gear. His time isn't bad, considering the miscue: 47.63 seconds with no plastered pylons. Mitch makes no big mistakes, but still manages to hit one pylon in the slalom. He runs a 46.31, a little slower than before.

Marcie is clearly feeling the two doses of Carlsberg. She announces before her run, "This is definitely a test—because I'm definitely drunk!" She knocks over two cones, but actually runs 1.25 seconds faster than before, a 57.91. Jeff also loses time trying to get the bike into first after the runaround, but still manages to beat his sober time by a whisker. He does a cone-free 49.70 after losing at least a second rowing through the poor transmission.

Subjectively, Mitch and Nick are quickly acclimating to their slightly drunken state and are performing well on the course. Their inhibitions are starting to fall away, but they are still sharp enough to keep the bike upright and between the cones. Their strong performances show up one problem with using expert riders: These guys spend so much time on motorcycles that they could likely still ride at an acceptable level of competence long after losing the ability to tie their shoes. What's more, the additional lap of the course takes off more time than the alcohol can put back on.

Both Jeff and Marcie seem smoother on their second round of laps, too. They show steadier lines around the course than in their first attempts, probably due as much to the extra practice than to any actual effect of the booze. For them, fear seems to be the main limiting factor in their sober performance. Two drinks appear to have taken away some of the healthy fear of crashing while leaving most of their riding skills largely intact.

ROUND 3: 0.05 percent BAC

As the riders down their third rounds, the behavior effects of the liquor begin to manifest themselves profoundly. Mitch, who showed a tendency to clobber the last three slalom cones during his runs, begins to argue in loud, obnoxious tones that those cones should be counted differently from the others. His arguments are regarded by all as ridiculous. Slightly hurt, Mitch announces that, as his alcohol level goes up, he feels increasingly misunderstood.

Jeff lies down on the warm asphalt in his new leathers and stays there, quite happily stewed. Nick barely manages to announce that his speech is becoming slurred. As the rest pile into their leathers for the next set of runs, Marcie broadcasts, a little too loudly, "We're having fun now!"

We give abbreviated field sobriety tests to the drinkers before the next runs. Marcie, who has been telling us all how drunk she feels, passes easily. She has no trouble walking a straight line, standing on one foot or touching her nose with her eyes closed. Nick has trouble finding his nose with his left hand, and Mitch is also shaky on proboscis location. Jeff hits his honker only three times out of four and becomes belligerent when the crowd notices.

With three rounds downed, the riders are approaching 0.05 percent BACmore than halfway to legally intoxicated [even closer these days]. Nick leads off the runs and promptly crashes going into the fast decreasing-radius corner. He ground the exhaust pipe hard enough to unload the rear tire and slide it, though he can't remember exactly how he crashed by the time he picks up the bike, restarts it and finishes his run.

Mitch is getting into the groove of the course. He clocks a smooth 46.06, finally completing a run without tagging any cones. Marcie rides cautiously, lurching a bit in the corners but doing well objectively: a 57.65 with no cones, her best so far. Jeff is turning each lap into a clown routine worthy of Jerry Lewis at his best. Karr can't find neutral going into the stop-and-hop sections, but he makes up for his ineptitude by flapping his arms and hooting like a wounded stork on his way around the Honda. He screams as the footpegs touch down in each corner, giving an emotional play-by-play the spectators can clearly hear over the din of combustion and grinding steel. He is funny, but slow: a 52.40 with coneage.

ROUND 4: 0.07 percent BAC

Mitch writes a note in my legal pad about how he feels: "Things are slightly weird, but I seem to be able to ride OK. Funny, huh? Anyway, Karr is really screwed up!!" He writes his name at the top of the page, spelling it "Mith."

Considerably sobered up by his recent crash, Nick turns a smooth 45.93 with two cones down, only slightly worse than his sober performance. Mitch, spelling ability notwithstanding, rides like a fearless maniac, his considerable talent and experience getting him through the course unscathed. Incredibly, he sets the overall fast time of the day, a pipe-flattening 44.82. Marcie is obviously feeling the alcohol, going slower and much more carefully than before, running a 1:00.37 after nearly toppling the motorcycle at the end of the slalom. Jeff has pulled himself together for this run, turning a 48.68 with one cone credited against him.

ROUND 5: 0.085 percent BAC

The three remaining drinkers are now officially drunk in California. As the riders continue their spiral into oblivion, their performances rapidly go downhill after the fifth round of Carlsberg. Nick runs a 47.50 with one cone. Mitch manages a 47.30 with one cone. Marcie announces she would never, ever get on a motorcycle in this condition. She runs a slow, careful 1:09.57 with no cones, climbs off the bike and staggers behind the van to throw up. It's the end of her drinking for the day. She will make one more run as her equilibrium returns, but her body has said in no uncertain terms it's time to call it quits to drinking. Jeff is still functioning, but he misses first gear on one stop-and-run, turning a 51.32 with no cones.

ROUND 6: 0.10 percent BAC

Nick can't find his helmet and gloves before his run. He complains he can't focus his eyes well, and that his motor control seems wooden. He's careful and slow, turning a 49.25 with no cones, 3.27 seconds off his sober pace. Mitch aborts one run, then turns a 48.21 with no cones after having a hard time getting the bike into gear. That's 3.5 seconds slower than his lap time just two drinks ago. Marcie bravely tries another run; she is slow and hesitant and runs 1:03.66. Jeff is loud, loose and hilarious. He misses first gear but manages a clean, slow run at 54.23.

ROUND 7: 0.115 percent BAC

Nick: "I can't concentrateI'm really wasted." 46.50, two cones.

Mitch is still holding his act together. He runs a 48.28, hitting one cone, yelling whatever comes into his mind at the top of his lungs.

Marcie: "I never knew throwing up could be so satisfying." She has hung up her leathers for the day.

Jeff: "There's an entire Christmas turkey in my helmet with me." He tries to remove his helmet without taking his sunglasses off, sending them flying across the pavement. He runs a valiant 53.07, with no cones downed.

ROUND 8: 0.13 percent BAC

The three riders are rolling, moaning, slobbering drunk. It's now become an exercise in animal management to get them to the bike with their helmets and gloves on. They all launch into long-winded discussions of their places in the universe just as their turn comes up on the poor, battered Rebel. Mitch has taken to fast, terrifying spins around the parking lot before his runs to "warm up the tires." He's warming up the footpegs more than the tires, but there's no way to stop him short of chaining him into the bed of the pickup. Jeff is spending a lot of time lying on the asphalt, face-down, crawling around like a lizard recently run over by a car.

Nick is barely able to breathe without adult supervision. He is suffering severe tunnel vision. "I can't see the ground," he announces, and then goes out to prove it. He misses first gear on the first runaround and almost topples the bike. He's all over the track. He takes out six of seven pylons in a tight right-hander, lurches back onto the course and finally tosses the bike away in the same decreasing-radius sweeper he crashed in before. He hits hard, scraping his leathers and helmet. He wants to get back up and finish, but sober heads prevail and walk the bike back to the pits to check it and Nick for damage.

Mitch's performance is almost supernatural. He's very, very drunk, but he manages to turn a 49.32, hitting only one cone. Jeff is having a hard time getting ready for his run. "You might remark," he informs me, "that I have to be on my knees to successfully zip up my leathers." Jeff is slow and jerky. He slides the rear wheel a couple of times and misses the handlebar when he tries to remount after the second run-around, nearly falling on his face. He finishes in 1:00.78, wheelies through the finish and slides into the dirt at the edge of the course.

Both Mitch and Nick want to try again. Nick appears much more sober than he did before his crash, so we foolishly let him run the course one last time. He stalls the bike and knocks it over on the second turnaround, completing the lap by running off the course, scattering pylons like so many dry leaves. We tie him down in the van with Ancras to keep him away from anything with wheels or sharp edges.

Mitch manages to put together another heroic run. He turns a 47.83 with no cones, almost 2 seconds faster than Jeff's best run of the day and about 3 seconds slower than his own record. Boehm has just enough concentration to complete the lap. At the finish he lets himself topple from the motorcycle to the ground. He just lies there, feet in the air, laughing hysterically at the desert sky.

Our testing gave us some valuable insight into the effects of varying doses of alcohol on the human condition, and some idea of how massive doses impair riding performance.

There is a big qualitative difference between experienced racers slamming a Rebel around the same safe, slow course again and again and trying to navigate a 150-mph musclebike home at night after the bars close. A couple of our riders were able to keep the bike between the pylons at fairly high BAC percentages. Neither would have even considered getting on a motorcycle in a street environment at a quarter of their final intoxication levels.

Street riding has no runoff area. Instead of soft, yielding rubber cones, streets are lined with cars, hydrants, Armco barriers and trees. Instead of fresh, clean, consistent asphalt, the streets are greasy, potholed, sandy and unpredictable. And instead of sober friends cheering at the side of the track, there are lurching Buicks, often driven by other drunks. There are old ladies turning left in front of you, just at the time you're least able to compensate correctly. There are policemen and highway patrolmen trying to keep you alive, even if it means taking you to jail and ripping up your driver's license. And there are other drivers who might get killed trying to avoid a drunken motorcyclist.

Our riders wound up in a huge, groaning, leather-wrapped pile on the ground, while the sober crew picked up pylons and peeled the masking-tape course markers off the pavement. As the caravan prepared to leave, both Jeff and Nick lost their lunches in the now well-established barf zone behind the Motorcyclist van. The trip home was a stop-and-go procedure, with cars, pickups and vans halting periodically as the drinkers returned Elephant malt liquor to the Earth from which it sprung. The final score: Carlsberg 4, riders zero. Cheers!

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)