Cycle magazine is dead. Long live Cycle magazine! It's been over 15 years since publication ceased on what many consider the best motorcycle magazine of all time. Cycle was first published in 1950 by Petersen Publishing, then by Floyd Clymer and Ziff-Davis, and finally by CBS, Diamandis and Hachette-Filipacchi. Through the leadership of Gordon Jennings, Cook Neilson and Phil Schilling, it advanced the quality of motorcycle journalism and provided a benchmark for other magazines.

Those who steered Cycle were men of letters. Jennings was an AMA expert roadracer and a self-taught engineer who persistently studied the world around him. Neilson was a Princeton man whose intellect, wit and command of the Queen's language could have taken him anywhere-but he chose Cycle. And Schilling likewise sidetracked a career in academia to push Cycle toward excellence. Along the way, Neilson and Schilling-with Jennings' early help and that of Pierre des Roches, Jerry Branch, Marvin Webster and others-built Neilson's personal Ducati 750 Super Sport into "Old Blue," the 1977 Daytona Superbike race winner. That was 30 years ago, and to commemorate the event Ducati recently introduced a short production run of 50 NCR-built New Blue track bikes. For $50,000, they're a terrific honorarium for the pair's achievement. What other magazine editors-from any field whatsoever-have been so pointedly honored? I can't think of another example.

While Neilson and Schilling's racing accomplishments will guild the record books forever, perhaps even more important is their contribution to motorcycle journalism. To understand what these guys-along with Jennings, Dale Boller, Jess Thomas, Dave Holeman, art director Paul Halesworth and publisher Tom Sargent-brought to motorcycling was incalculable. From sheer technical brilliance, to creating the world's first superbike comparison, to quoting literaries such as T.S. Eliot in road tests, they leveraged a far more studied and intellectual approach. And in doing so, they helped erase the Scarlet Letter motorcycling wore at the time. Longtime readers may recall with some pain the second-class treatment motorcyclists received back in the day. I recall being bullied by cars and hassled by cops, recollect a major hotel that would not serve me, and remember that my own church would not permit motorcycles to be parked on its property. Amid such negativity-including disturbing impressions that films like Easy Rider created-Cycle magazine simply illuminated. Beautifully written, thoughtfully created and staffed by smart, savvy professionals with a useful world view, it helped show that motorcycling was actually an intelligent pursuit.

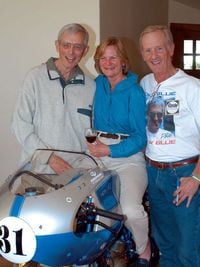

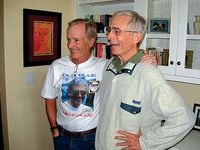

Earlier this year, it all came home to roost. With Schilling unable to attend New Blue's unveiling in New York or its ceremonial AHRMA race at Daytona, Ducati and NCR arranged to have a bike shipped to California for him to see. That much Schilling knew. But what he didn't know was that behind the scenes, some two dozen Cycle employees and contributors-from the late 1960s to its days with Schilling at the helm-rode, drove and flew in from across the country to surprise the man Neilson described as "the real brains behind the magazine and the finest editor I've ever known." Deceptively lured to a casual lunch at a friend's house, Schilling had scarcely taken a sip of his pinot noir when a thrumming sound permeated the neighborhood. It grew louder, with the jingling of a dry clutch thrown in, and suddenly a flash of silver and blue appeared on the front walkway, then darted inside the front door, through the hallway and right smack dab into the living room. Jaw agape, Schilling watched in amazement as Neilson himself rapped the throttle, blasting the entire house with sound. A massive grin on his face, he shouted, "How ya' doing, Schiller?" as almost the entire brain trust of Cycle, hidden outside, streamed in and around him. Dry eyes were few.

Like most reunions, it didn't last long-nine hours or so. And given the distances people had traveled and the uniqueness of the occasion, everyone knew it would probably never happen again. Not like this. At evening's end, Neilson put it eloquently. "We may not ever do this again," he said, "but what matters is that we did it this once."

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/W2F2QHY4VVFM7AJMV7N5SHSBPY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AFW7GSF47NEAPMYGVJ5RMMBDNE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GJHLAGRYXBH6BGCISATHTBLU24.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HVZE5SURNNAYDLJVQ2BTWECIVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/NP5FHV6NRBGX5LQRUK3CA6A4BM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IE37M3MVXZAAVGHNGQVVL5YY5U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5L4R2YWNM5BNFCY3NVYUUCXM3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/UMAEHOQO55GWXFPIFP2MYGPGHA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S634O4RKRRHWHIRX5ZEDVV2HJY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TI3FVHFEHVDMFKIWWA3GZIFASE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/W3MVEL2BIZBHPEXLPVE4MAYNWI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/DF7G3Y7H6FBJRDLHR2ISRMHKEU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3ETQKXY6V5E3BPT5AGNXOVMJWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MIMXIJGIJNHOJPJCNBNYK754HE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IB75G7P4SBGDVOXI5LOD5ALC54.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7EUGVL7GEJBTFGMNOEYQKRUCBM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QFW7MEDGMBGGZKT74WTC6JGZDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U6W36NIHS5CJVO5LYJIPQINSIM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/I7OKI53SZNDOBD2QPXV5VW4AR4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2JIELXVLZJCSXIINID53DIC45Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4PLHXJPL5ZFTFN5F4RA3S7UZ6I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IH52EK3ZYZEDRD3HI3QAYOQOQY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/C7F6P22LGZENVNWMPDELKY3PRI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4XK7JL24FCUTKLZWUFVXOSOGE.jpg)