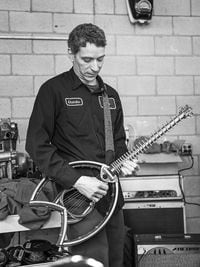

Each motorcyclist’s metaphorical mecca is different, but if there’s a perfect example for the vintage Honda enthusiast, it would be Charlie’s Place. At the far end of a quiet industrial alley in Glendale, California, Charlie’s Place is a haven for classic Honda twins and fours. Walking through the doors is like stepping back in time—classic records adorn the walls, a speaker broadcasts the tunes of a corresponding era, and a lone soul in a blue button-up work shirt intensely toils away at his craft. Owner Charlie O’Hanlon isn’t one to tout his immeasurable knowledge of classic Hondas. Instead, his steadfast approach to the meticulous restoration of each individual motorcycle alone speaks volumes.

Each motorcyclist’s metaphorical mecca is different, but if there’s a perfect example for the vintage Honda enthusiast, it would be Charlie’s Place. At the far end of a quiet industrial alley in Glendale, California, Charlie’s Place is a haven for classic Honda twins and fours. Walking through the doors is like stepping back in time—classic records adorn the walls, a speaker broadcasts the tunes of a corresponding era, and a lone soul in a blue button-up work shirt intensely toils away at his craft. Owner Charlie O’Hanlon isn’t one to tout his immeasurable knowledge of classic Hondas. Instead, his steadfast approach to the meticulous restoration of each individual motorcycle alone speaks volumes.

In 1985, O’Hanlon moved to San Francisco after spending his youth in Manhattan. Pursuing an education at the San Francisco Art Institute led to an interest in photography and ultimately a venture into mechanics. Due to the popularity of motorcycles among the small San Francisco communities, O’Hanlon developed an interest and appreciation for the culture surrounding these machines. He set up shop in San Francisco’s Mission District, establishing himself as a noteworthy business owner and gaining many new customers and friends along the way. After returning from a short business-related foray to Germany in 1992, and encouraged by a resentment for San Francisco’s misplaced anti-motorist attitude, O’Hanlon moved to Los Angeles and set up his repair shop on Beverly Boulevard.

At first O’Hanlon accepted any motorcycle that came his way, but after some time honing his prowess he began to gravitate toward Hondas from the ’60s and ’70s. After becoming enamored with a certain red CB77 Superhawk, O’Hanlon determined that the primary focus of his business would be these same classic-era Honda motorcycles, due largely to their reliability and low cost (at the time). O’Hanlon was intrigued by the quality of components and found the Hondas possessed better overall craftsmanship in general.

Conversely, he discovered that these bikes were not without their inherent flaws, and the collective Achilles’ heel seemed to lie with the high-maintenance ignition systems.

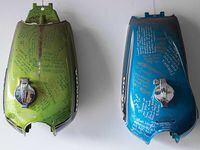

Compelled to improve on an age-old design, he began designing an electronic ignition that all but did away with the antiquated manual points system. It was the success of this venture, along with exposure in local printed media in retro-obsessed Los Angeles, that gained O’Hanlon’s small shop distinction and a steady stream of frame-up restoration requests. O’Hanlon worked to amass a stockpile of hard-to-find parts and period-correct components, which now decorate the shelves of his shop. Rows of spare cams, uncommon exhausts, and exceptional examples of pristine tanks can all be unearthed by a curious eye. A prolonged gaze will eventually reveal a few unique oddities that integrate O’Hanlon’s other interests, such as a handmade guitar built from the vacant carcass of an old CB350 tank or various metal sculptures incorporating the leftover parts from previous handiwork. Everything has a purpose in O’Hanlon’s eye, and the usefulness of any single item is not lost upon him.

Today you’ll find O’Hanlon working meticulously at his many projects and undertakings, all the while adhering to his main principles of structure, function, and aesthetic. “Everything has to be at the highest standard, all the time,” O’Hanlon remarks from behind an impeccable example of a CL77 Scrambler he’s working on for a customer. “It has to be done so that it blows your mind how good the bike is. It’s not even worth it to me to do it any other way. See, for me, life is about getting out there and getting to the top. I work very hard, but I do so because I get the results I want to get. I’m doing what I really enjoy doing.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)