From the October 1938 Issue of Motorcyclist magazine

The accompanying article departs from the usual editorial policy of reporting only motorcycle activities. It appears in this issue first because it is an outstanding accomplishment in speed and second because motorcycle record trials were held on the Bonneville Salt Flats within three days of the time the automobile records were established. In this description of the course is much which helps explain what trials on the salt are like. It is hoped our readers will the more enjoy stories of our own records in Utah as a result of reading about John Cobb and Captain Eyston.

-Ed.)

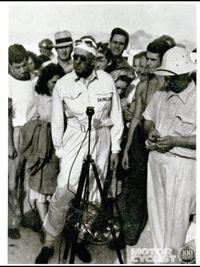

“The battle of the century,” is a phrase taken from the lips of expert observers who were “on the salt” during the recent sporting struggle between John R. Cobb and Captain George E.T. Eyston.

Although these observers were specialists, each watching, recording and studying various phases of mechanical and physical performance, they could not but thrill to the fact that before their eyes was being waged a battle for supremacy in automobile speed which it is unlikely they or anyone else will ever witness again.

History was indeed in the making at Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah, when two speed men were present at the same time, each destined to set a world’s record in the brackets around 350 miles per hour, and when old records should tumble to the extent of as much as 32 miles per hour.

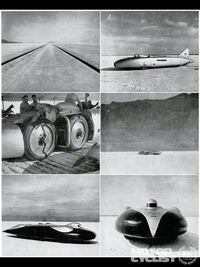

Early in the second week of August Captain Eyston made his first trial run, and turned 280 m.p.h. This was to test his equipment after its trip overseas and to determine certain factors preliminary to his record trials. On about the 15th of the same month John Cobb made a trial run with his newly designed Railton and turned 300 m.p.h. He likewise was preparing for the record trials.

These speeds, tremendous in themselves as compared to the capabilities of ordinary cars or even racing cars, were turned almost casually as the two Englishmen girded their loins for what was to follow.

The same week Captain Eyston turned slightly over 300 m.p.h. and that seemed to end the preparations. Word was sent to the American Automobile Association that all was set for the timing equipment and the real trials.

Timing, as is well known, was done by means of the photoelectric eye. The equipment, like the machines it was to time was highly specialized. It had to record the passing of an object at the rate of approximately 520 feet per second which is about 2/3 the speed of a bullet from an army automatic pistol. A time delay relay was employed so as to enable the machine to hold down the type which was to record the time on a ribbon of paper.

Since the actual trials were to be worldwide news, radio moved in. KNEF set up a tent which housed a complete and very efficient low wave broadcasting unit. KBID and KRIC were then set up one at each end of the 13-mile course. These stations broadcasted news from their respective ends of the course to KNEF and that station broadcasted to KSL in Salt Lake City where in turn it was sent out over the air for the country to hear. And while this system tended to serve the nation and the world, it also tended to serve those who were officiating at the trials. By the simple means of turning on car sets, it was possible for people at one end of the course to hear and even to communicate with those at the opposite end. The KNEF announcer was so located that he commanded a view of the measured mile which was in the center of the course and thus the whole thirteen miles was policed by radio.

Black lines, about 12 inches wide had been carefully traced along the outer limits of the course. These were put down by state highway equipment much as pavement lines are marked, but an asphalt like mixture was used that impregnated itself into the salt.

The course was shaved with specially adapted road equipment and the 13-mile stretch was really as smooth as any surface could be. In fact, among experts, the course at Bonneville Salt Flats is considered the best for speed trials of any in the world, so far as surface is concerned.

The first official attempt was made by Captain Eyston on August 24th. On his North run he turned 345.15 m.p.h. On the South run the timer failed to register. Reflected light from the very white salt was such that it prevented the sensitive eye from registering the fleet passage of the car.

Mr. H.T. Plumb, one of the nation’s foremost authorities on light, and district engineer for the General Electric Company was called in. He made certain recommendations and following that a black strip was painted on the salt at the location of the eye. Black boards were put behind the light source and a black strip was painted on the car. This corrected the timing difficulties.

On August 27th the Captain tried again. On his North run he turned 347.49 m.p.h. and on the South run he turned 343.51 m.p.h. This gave him an average of 345.49 m.p.h. and increased the old record by a little over 32 m.p.h.

Then on Tuesday morning, August 30th, John Cobb made a trial. No figures were released to the public, but expert observers estimated that he had traveled about 325 m.p.h. He announced that after making some changes he would try again.

At that point the weather stepped in and rain prevented another trial until September 12th.

The salt beds are approximately 45 miles long and are from about 25 to 40 miles in width. The thickness of the salt varies considerably, the deposit resting upon the undulations of an old ocean bed. Rain falling on the beds soaks into and through the salt to the mud flats below. Each day, after the rains are over, the sun draws a percentage of this moisture to the surface. Around noon many parts of the beds are covered with a brine. As the sun moves on the moisture that has not been absorbed into the air works back into the salt. But in the process, salt from the brine forms a deposit in weird designs over the flats. Locally this is spoken of as “bloom.”

This action goes on even in fair weather and that is why the course must be worked every day with drags and occasionally scraped. Following rains the amount of work necessary for a good course is increased and thus the long delay until September 12th before Cobb was able to run again.

That time his first run was South and he turned 341.25 m.p.h. On the run North he turned 343.8 m.p.h., or an average of 342.5 m.p.h. He missed by approximately 3 m.p.h. and possibly that is the only figure out of most that came from the salt beds that the ordinary laymen could understand. But even when thinking of the lowly 3 m.p.h. it is doubtful if Mr. John Public stopped to realized that at that speed it represents but nine hundredths of a second on the watch. It takes the long Thunderbolt at 350 m.p.h. 1/16th of a second to pass before the eye. Thus Captain Eyston had beat John Cobb by slightly more than a length of the Thunderbolt. It was a close struggle for world supremacy and little wonder the experts, accustomed to thinking in small fractions of time, high speeds, and who fought so valiantly to add even one mile per hour to the speed of either car, should thrill at this “battle of the century.”

Another interesting factor at this stage was that the above run was made with the highest wind of the trial, a velocity of 5 m.p.h. The wind was on his tail during the North run.

Then on September 15th Cobb made another attempt and set the average of 350.2 m.p.h. It was a new record and he was the champion of the world.

Captain Eyston, anxious to make the best of conditions, decided to run on the 16th. Going North he turned 356.44 m.p.h. and going South he turned 358.7 m.p.h. The average was 357.5 m.p.h. Thus was Cobb shorn of his title of a day and Eyston moved back in as No. 1 automobile speed king.

Cobb announced it would take too long to make further changes in his equipment, and for this year and his camp, “school was out.”

There is a way in this world of remembering things in round numbers-even speeds. First we thought of a mile a minute, then two miles a minute and so on along that long difficult trail of speed. Captain Eyston has cherished a desire to be the first to turn six miles a minute. For that reason he made further changes and decided to make another trial even though he held the record.

On September 21st, Eyston made his last effort to get the six mile a minute title. He turned up tremendous speed according to witnesses, but mechanical trouble developed which damaged the car to such an extent that he, like Cobb, decided against further changes on the ground.

That ended the famous battle and Captain Eyston departed with the record.

Many people read the results of that contest and ask, “What is all this speed about?”

As already stated, experts were on hand studying not only the temperature of the air, its humidity, and wind velocity, but they kept equally careful records on temperatures of everything from the motor parts to the tires. In connection with the latter, they answered the question, “How much will present tires stand?” Dunlop tires were constructed for both cars along very definite specifications. They know that these tires will stand the terrific strain of centrifugal force up to a speed of something between 360 and 400 m.p.h., probably slightly over 360. That is valuable to all tire companies, on methods of construction of everything from the tires we use on stock cars, to what are used on high landing speed planes, and racing cars.

Cobb had no radiator. He cooled his engines by water from a 75 gallon tank which carried a certain amount of ice in the water. Cobb ran without a tail fin. Later Eyston removed the radiator from his Thunderbolt, mostly to accomplish streamlining through a closed nose, and also removed the tail fin. He installed a tank and ice and cooled with that the same as Cobb.

Cobb’s machine was equipped with water cooled brakes. He used a single girder frame, an unconventional design in itself, with a motor on each side. He used 2 Napier engines (W type) 12 cylinders each and both were supercharged. They were rated at 1,250 h.p. each. His rear motor drove the front wheels and the front motor drove the rear wheels. When Reid Railton designed the machine he planned the body first, in order to accomplish certain principles of streamlining, and then designed his mechanical features to fit the body. As a result the car has a crab-like appearance the front axle tread being 5 feet six inches and the rear, three feet six inches. The driver’s seat is ahead of the front axle in the very head of the car.

Captain Eyston sits amidships in the Thunderbolt. He employs two Rolls Royce engines out of several designed for Schneider cup competition (the fastest seaplane record over a mile). His are of the same type as the one used by Sir Malcom Campbell when he established his record of 300 m.p.h., and the one used by Campbell in securing his water record of over 127 m.p.h. This type of motor also held the air speed record until recently when the Italians took it away from England at 442 m.p.h.

Eyston’s car had 8 wheels. On the rear were duals, while forward were 4 separate wheels to guide the 7½-ton car. His engines developed 3,650 h.p. Cobb’s car weighed 3½, tons.

Traveling on the ground where most of us do presents many difficult speed problems that are not experienced in the air. Thus both Cobb and Eyston are doing something more than competing for glory. They are scientists of speed.

Captain Eyston has a V.D. emblem on his car. It signifies 25 years of driving without an accident. That in itself may offer a thought to modern safety experts. A great cry is made about speed. Actually it is the understanding of speed that counts. The fastest traveler on land; the fastest driver in the world, drives 25 years without an accident.

“The battle of the century” is over but the battle of the modern age is still on. And from the former undoubtedly comes much of value for the latter.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)