Well it nearly happened and ironically right smack in the 10-year period in which motorcycling exploded around the world: the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Robert Lutz, marketing guru for the likes of BMW, Ford, and GM during his 60-plus-year automotive career, saw it firsthand in ’72 as BMW’s newly appointed automobile sales manager. “All the pressure from within the company regarding motorcycles at the time,” Lutz remembers, “and especially from the finance guys, was to shut down the bike business. Many in upper management wanted to just kill it—or at least sell it.”

The reasons for this in the face of booming motorcycle sales are obvious: The Japanese were flooding the market with cheap, cute, and dependable motorcycles; they were also beginning to build larger and more sophisticated machines, the crowning achievement of which during the '60s was Honda's magnificent CB750. Equally problematic was BMW's product line and reputation during that time. BMWs were stodgy looking, built with dated technology, and appealed to an older audience, a far cry from the young baby boomers then controlling the market with their wallets and (largely) desiring what the Japanese were offering.

“When I joined BMW in ’72, the company was building about 200,000 cars annually and only 10 to 12,000 motorcycles,” Lutz says. “Pretty insignificant volume, really. Our US volume was declining, with most sales to police and federal agencies. Retail was nearly nonexistent. The Japanese had all the cool stuff: overhead cams, multi cylinders, disc brakes, advanced and sexy stuff. We just didn’t have it, and were treated as a bit of a joke by the magazines. They’d write, ‘BMWs…nice touring motorcycles for elderly people,’ and stuff like that. Not a reputation that boded well for the future.

“When I joined BMW, literally no one was in charge of the motorcycle division,” Lutz continues. “Part was controlled by sales, part by engineering, part by design, et cetera. The group was basically leaderless and had very little in the way of resources. So I asked my boss if I could pull things together and give the division some leadership. I told him they were desperate for a direction, a plan. He said okay but added this: ‘Just don’t ignore the job we hired you for!’ So I called everyone involved with motorcycles together and pretty quickly hammered out a plan, which everyone agreed was the right one.”

Instead of competing against the Japanese with cylinders, horsepower, and flash, BMW would go above them and build a fast, sleek, smooth, and sexy sporting motorcycle that evoked premium quality, style, and high-end panache—attributes Japanese motorcycles mostly lacked at the time.

“We decided that we’d send a signal to the Japanese that we were back in the bike business with a high-priced, premium motorcycle that enthusiasts would really want,” Lutz says. “Right off we decided on a larger engine, and 900cc seemed right, as there were all sorts of 900cc kits on the market already. It’d have disc brakes, a five-speed gearbox, and beautiful detailing everywhere.” Lutz is describing a substantial leap for BMW here.

“It wasn’t easy to sell it to upper management,” Lutz remembers. “Most thought we should shut down the motorcycle division entirely, as it wasn’t making any money. But because we could use much of the R75/5’s foundation for the new bike we’d envisioned, the investment wouldn’t be huge. [The /5 debuted in 1969 and featured an entirely new, and quite good, engine and chassis.] So they agreed. We just needed to make it look right.”

Enter Hans-Albrecht Muth, a toolmaker-turned-auto-designer recently hired, like Lutz, at BMW for its auto-interior design department. Muth was also a motorcycle fan and within two weeks of moving into the design department found his way to the motorcycle offices—and the desk of Hans-Gunther von der Marwitz, who was as close as there was to a motorcycle development manager at BMW.

“I knocked on his door, walked in, and got some gruff questions right away,” Muth shares. “‘Who are you? What do you want?’ he asked. ‘Who does motorcycling styling here?’ I asked back. ‘We do,’ he said. ‘Why do you ask?’ ‘Well, that’s why our motorcycles look the way they do!’ I said.”

Muth assumed Marwitz would be offended but was surprised to be asked if he liked motorcycles or rode. When Muth replied in the affirmative, “He [Marwitz] surprised me, saying, ‘Okay, you do it!’” Muth says. “It was amazing and so German: chop, chop, right to the point. So I immediately got a second job, unofficial of course, and in the coming months I had to hide my motorcycle work from my real boss whenever he would visit the studio.

“A few days later,” Muth continues, “Marwitz asked me to see Lutz about the motorcycle designs we’d talked about. Lutz was moving into his new office and had already put a large poster of a beautiful racing motorcycle on his wall. He told me the company was already working on a new generation of bikes and did I have an opinion how a premium, sporty German motorcycle should look. He pointed to the poster, looked back at me with a cigar in his mouth, and smiled. ‘Yes,’ I said. And with that I headed back to my studio. It wasn’t a long meeting.”

Muth developed three sketches, the primary one the shape that would become the R90S in 18 months’ time. “It was sporty and had a big tank,” Muth remembers, “and would carry two riders in comfort. As far as the overall shape, I sketched it exactly as I envisioned a modern BMW should look, with a sporty tail in the spirit of the classic English racing bikes. But what it needed most, I thought, was a face, like an automobile has a face. And that idea, along with the small racing fairings of the day, is where the idea for the cockpit fairing came from. Also, just as a fighter pilot needs a place to relax and concentrate on what’s coming, whether enemy or weather, the new bike needed a cockpit and instrumentation tucked behind that wind-cutting fairing—gauges, and such, and a clock too.

“The two-tone color scheme of the first R90S came easily to me,” Muth continues. “Black had been BMW’s only color until the R75/5 came along in ’69, but during S-model development I remembered a bicycle I’d painted when I was 13 or 14 back in Germany. It was black but had a silver section. And as I thought about it, it was perfect. The black would recognize the past and BMW’s history, while the silver would represent the future, where BMW was headed. Melding them as we did was very difficult when it came time to paint the production bikes, and we had a lot of help from the very talented women we hired to do striping and such. But it was worth it, as the color ended up being very popular.”

Muth did a second color a year later, after visiting Daytona and seeing the BMW racers do well there, called Daytona Orange. “I called it Egg Yolk,” Lutz says. “And I didn’t like it. But both sold well, and both are iconic now.” Some enthusiasts today say, mostly in jest but not totally so, that Daytona Orange bikes are a tick faster than their silver siblings. Others disagree vehemently.

Lutz recalls the first public showing of the R90S at the Paris Auto Show in late ’73. “It was an absolute success,” he says. “It was beautiful. It was sexy. It made a statement. It was a 900. And it was expensive, too, but no one balked at the price. Internally, we loved it because margins were higher than on some of our sedans! We sold out immediately. It was attracting the customers we wanted too: guys who’d dreamed of a BMW years ago, when they were younger, and who could now afford one. And professionals too—CEOs, doctors, lawyers, et cetera. It was amazing to see such a premium product take off so strongly.

“We’d planned to build a few thousand,” Lutz continues, “but they sold so well we began to run out of components. We had to quickly reorder things; we switched carburetor brands for a while and had to hire more painters for the difficult paint scheme. We did not want to compromise on quality at all, and we sold every one we made.”

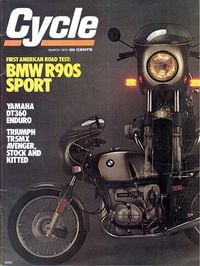

Generally positive press from the magazines helped. In its March 1974 exclusive test, Cycle found the S-model smooth, quiet, reasonably fast, dead reliable, a solid stopper, and very, very comfortable. Editors questioned the $3,400 price tag, writing that the price "is hard to justify." "The Kawasaki Z1," Cycle continued, "able to do about 85 percent of what the R90S does best, and capable of some things better, is cheaper by a gaudy $1,435." That amount was nearly half the 90S's price tag! Other magazines complained about a lack of cornering traction and some wallowy high-speed behavior, much of which was caused by low-grade tires and the fairing's less-than-optimum aerodynamics (it allowed the front end to lift at speed). But in the end most editors were swayed. Cycle finished up this way: "In short, it's a helluva motorcycle for too much money."

The R90S did surprisingly well in superbike racing, too, with Reg Pridmore winning the 1976 title aboard a Butler and Smith-prepped S-model tuned by Udo Gietl and master fabricator Todd Schuster. Steve McLaughlin and Gary Fisher also won Superbike races on B&S R90Ss, though these machines were nothing at all like the production machines, as they used Rob North frames and tons of titanium inside the engine so they wouldn’t come apart at speed. “We blew up a lot of engines during development back in the day,” Gietl says.

Lutz probably best sums up the impact the R90S had on motorcycling: “To me, the R90S is arguably one of the most significant motorcycles ever made. It may be egotistical to say this, but I believe I am the founding father of the idea behind the R90S. The S made BMW motorcycles respectable again! Not only outside the company, with the magazines, and with buyers, but within the company too. It proved to BMW it could compete and make money in the bike business, and the money the R90S made helped pave the way for future motorcycles, many of which are iconic themselves.

“What followed the R90S was a willingness on the part of upper management to invest in the motorcycle business, and that allowed machines like the R100RS, the GSs, and the K- and R-series bikes to come later,” Lutz continues. “Suddenly, after the S-model took off, there was a more adventuresome spirit within the company, more boldness. We see that to this very day, and it all came from the R90S.” Lutz’s ownership today of a handful of BMW motorcycles—some new, some old—backs up his words nicely.

Yes, it would be strange indeed to not have GSs and RSs and RTs around to ride and admire. But thanks to the R90S, they’re all out there, their little blue and white propellers spinning proudly and happily.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)