"That was all him?"

That's the typical response when you start laddering the accomplishments, firsts, inventions, attributions, and history of Glenn Curtiss, the guy whose name barely budged the needle when you first said it.

An incomplete list: He designed and built his first motorcycle in 1901; designed and built the first American V-twin motorcycle engine in 1903; designed and built the first American V-8 motorcycle engine in 1906; and was a record-breaking motorcycle racer who routinely kicked Indian and Harley-Davidson 's butts. He was also the "world's fastest human" after going 137.3 mph on his Curtiss V-8 motorcycle in 1907. He is reputed to have created the motorcycle twist grip and definitely manufactured the Curtiss, Erie, and Marvel motorcycle brands.

Still more: He designed, built, and flew his first airplane in 1908; earned American Pilot's license #1 (even though the Wright brothers had already flown); earned French Pilot's license #2; made America's first pre-announced public flight; flew America's first long-distance flight; won the first international prize for air speed; and won Scientific American's Inventor award so many times they retired the trophy. He was the father of US Naval Aviation; created the airplane that accomplished the first takeoff and landing on a Navy ship; literally created the US aviation industry; and is a holder of 87 patents.

Yeah, that was all Glenn Curtiss.

Problem is, guys like Harley and the Davidsons and the Wright brothers get all the ink and satisfy most people's curiosity quotient on the origins of either American motorcycling or aviation, and they never seem to get to Curtiss. They should. Those other guys are famous for just one thing each. Curtiss, he did both—and then some.

Glenn Hammond Curtiss was born May 21, 1878, in Hammondsport, New York—this beautiful little map dot in upstate New York's Finger Lakes region was home to inviting Victorian porches, a tree-shrouded town square, and, oh, give or take a couple thousand folks, tucked into the southern shore of Keuka Lake.

But some kid born in his grandfather's Methodist parsonage was no big deal, even there, even then. Besides, Hammondsport, with its steep, cradling, vineyard-encrusted hills was already famous as the "Home of the US wine and champagne industry." But before he was finished, Curtiss would add another, even greater, claim to fame for this whisper of real estate: He made it a bedrock of American motorcycle and aviation innovation and industry. Hammondsport has never stopped thanking him.

"The community, the lake, the hills, they all had an input or were a factor in Curtiss becoming what he really was," says Ralph Brown, a local Curtiss historian. "If it hadn't been for the hills, would he have ever invented [his] motorcycle? If it hadn't been for the lake, would he ever have conceived of the seaplane? And, if it hadn't been for a small community, in which you could do these things, and have local support, you have to wonder if Curtiss would have ever achieved all the things that he did."

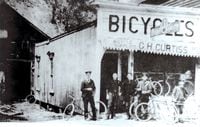

Most of the buildings in town associated with him are gone now. But there are picturesque "Glenn H. Curtiss Heritage Trail" placards in all the right places, with old photos of what used to be. His bicycle shop is now the post office parking lot. His home was on the hill behind where the big elementary school building is now. The foundation is still there, as is one of the motorcycle factory buildings that was next to the house, now used as a storehouse.

Even as a boy, Curtiss had a reputation as a sort of Mr. Fix-It. He had a real aptitude for taking things apart and putting them back together. Often better, so the stories go. He discovered bicycles in his early teens because they were the cool new things in the 1890s; he really liked the cool new things and seeing what he could do with them. In no time he had a shop repairing bicycles. That morphed into designing and building them. More than that, he raced—well enough to win a fair number of bicycle championships. (He tended to be a bit competitive.)

In about 1901 he discovered motorcycles, because now the cool new thing was putting engines in bicycle frames. Curtiss knew about bicycles. He didn't just know how to build them; he knew how to punish them while racing, so he knew where the strong and weak parts of a bicycle frame were—especially important if you were going to put an engine in one. He bought a mail-order engine first, but that deal lasted about a mayfly's lifespan. By 1903, he'd designed and built America's first V-twin motorcycle engine (Germany's NSU made one that year also; Harley-Davidson produced its first V-twin in 1909). Three years later, he built the first American V-8 motorcycle engine. The first carburetor he ever made he fashioned from a tomato can.

Legend has it that on one of the first trials of his new bikes, Curtiss was so excited about his powerful new engine that an essential accessory called the brake totally slipped his mind. Another version of the story says the brake he put on failed. Either story's more fun to tell than to verify. More pragmatic Curtiss historians will tell you he was too much of a perfectionist to have let either of those lapses happen. In truth, some dates and stories conflict in the Curtiss biography, typical of attempts to fashion significant history from insignificant beginnings.

But the story's ending is always the same: He wicks his bike up at the top of Shethar Street (Hammondsport's main drag) and, for whatever reason, can't slow the sucker down and rides it right into Keuka Lake at the bottom of Shethar Street. Which slowed it down completely. The lake's waters would save him more than once.

Another story, also apocryphal, but with a more serious bent, was about Curtiss' possible invention of the motorcycle twist grip: "Now he did later develop the twist grip. In fact, some sources claim that he invented it, but we don't know that's a fact," notes Kirk House, former director and curator of the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum. "He certainly was an early user of it, and it may well have been at least an independent development. According to the story, he was twisting a box—he had just taken an inner tube out of the box and was twisting it as he was talking to someone in the shop—and all of a sudden realized what he had and he dashed into the back room to mark it down. So they created the twist grip from there. That is how the story goes, anyhow."

Curtiss named his new motorcycle line Hercules until he found out the name was already registered. Soon after, the Curtiss name, and its iconic semi-script logo, appeared. Curtiss himself, he was more focused on building the best—and fastest—motorcycles, ones he would race against the likes of Indian and Harley-Davidson. And boy, were those Curtiss motorcycles fast, and was the boss man ever a talented racer. He routinely beat the others, setting and smashing records along the way—like he did on a famous Decoration Day (what would later become Memorial Day) in 1903, riding his new V-twin motorcycle.

According to Kirk House: "He went down to New York City, I believe it was in Brooklyn, and it was our understanding that he had the first twin-cylinder motorcycle. He got into a hill climb down there, and there were two professional riders on 'chain' driven Indians, and everybody was expecting them to finish one-two because that's typically what they did. They raced very well, but then Curtiss took off on his twin cylinder and just shot up the hill and shattered their time. And then he jumped back on the motorcycle, zipped across town to Yonkers, and jumped into another race over there. He won that 10-mile race, set a speed record, and became American Amateur Champion, all on the same day as getting the trophy for the hill climb at the other end of the city."

Undoubtedly though, Curtiss' biggest motorcycle success, and fame, happened on a Florida beach in January 1907. Fitting one of his new V-8 engines into one of his frames, he went down to Ormond Beach—one town north of the not-yet-more-famous Daytona Beach—and proceeded to go 137.3 mph on that same hard-packed sand that would, some decades later, birth a whole new world of motorsports in Daytona. For now, though, think what 137 mph meant in 1907. It was unheard of, unimaginable. The biggest locomotives couldn't even go that fast. Nothing could. Most of the bikes of the era still had single-cylinder engines. Yet Curtiss and his own V-8 went 137.3 mph. His brake? A single wedge of angle iron welded to an extension and bolted to a pivot point under his left foot that he could press against the rear tire. That was it. Seriously. This gutsy feat made him the "Fastest Man on Earth," a title he held for 23 years until 1930. In truth, he set three world records that time in Ormond Beach—for outright speed, plus new records for single-cylinder and twin-cylinder machines, all on Curtiss bikes.

And right in the middle of all this frantic creating and building and racing and record setting, it turns out that Curtiss' motorcycle engines are also just what the men developing these newfangled dirigible things are looking for. Lightweight, powerful engines they can fly with. (The V-8 engine he ran at Ormond Beach was actually a design he'd developed for dirigibles.) Aeronautical people begin to call on Curtiss. One thing leads to another.

But even as Curtiss transitioned from motorcycles—about 1914 when wartime orders for his Curtiss Jenny airplane overwhelmed the company's manufacturing capacity—and turned the bicycle business, now under the Marvel brand, over to his friend and former bicycle racing competitor, "Tank" Waters, his experience on two wheels would make a major contribution to American flight. His bicycle and motorcycle racing experience defined his "uncanny" natural flying ability. He knew how to lean to initiate turns and so developed shoulder harnesses with which to control his early airplanes' rudders. Curtiss knew all about the basics of flying before he ever left the ground.

In the end, Curtiss would most likely never have gotten into aviation if it weren't for his love of speed and motorcycle racing and the lightweight engines both required. As for Hammondsport's role in all this, historian Ralph Brown provided the perfect coda: "If you go back to, say, 1910, it may have been the only spot in the world where you could have seen, on the same day, a motorcycle, a steam locomotive, a steamboat, an airplane, and a seaplane just by standing in one spot. They were all right down here at the lake."

And it's mostly because of Glenn Curtiss.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)