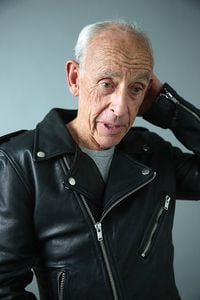

"I don't know how I survived that…" Malcolm Smith says that a lot these days.

I've heard the phrase plenty these past few months as I've sat with the man, recording nearly every word and digging into the details of his youth, his motorcycles, his racing, his family and friends, On Any Sunday, and the trappings of what can only be regarded as a truly amazing motorcycling life. All of that is for his upcoming autobiography called, no surprise, Malcolm! The Autobiography.

I understand why he questions his good luck. I haven't counted, but Malcolm probably had a dozen near-death experiences during his first 18 years, six on Canada's Salt Spring Island (tucked next to Vancouver Island) and the following dozen in San Bernardino, California.

Not just motorcycle-oriented danger, either, as Malcolm didn't start riding until he was 13. We're talking a near-drowning in the ocean; homemade push-karts, usually ones aimed straight downhill and often into busy intersections; go-karts with engines way too powerful for the chassis surrounding them; hopped-up and stripped-down automobiles that were little more than engines, frames, and wheels, really, with wired-on apple crates for seats; and bulldozers. Yep, bulldozers.

Even Malcolm's birth in March of 1941 was a scary affair, a botched C-section that left his mother, Elizabeth, with an infection that nearly killed her. Once she recovered, Malcolm, Elizabeth, and his father, Alexander "Sandy" Smith, settled down on a coastal sheep ranch the couple had bought a year or two earlier on Salt Spring Island.

The word amazing probably doesn't do Sandy Smith justice. He was born in 1859 in Scotland, and over the next 60 years became one of the most celebrated explorers, guides, and gold miners in Alaskan, Yukon, and Klondike history. Sandy Smith was 82 when Malcolm was born. (Do the math.) Malcolm's mom had no idea he was 80-plus when she married him (she was in her mid-thirties and thought he was in his fifties) and only discovered the truth after she was pregnant with Malcolm. Smith was an adventurer in the truest sense: tough, in superb shape, daring, and highly disciplined. Malcolm would inherit plenty of his father's traits and also several from mom: hard work, honesty, and compassion.

After WWII, the Smiths moved south to Southern California, Sandy and "Betty" looking to buy a small hotel in the Palm Springs area. There wasn't nearly enough money for that, so they settled in a small home against the mountains of San Bernardino, Betty teaching school and 88-year-old Sandy working at a local Air Force base, showing some of the young guys up in terms of productivity.

For six-year-old Malcolm, San Bernardino was heaven on earth—especially the flood-control ponds, levees, trails, and orchards that dotted the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. From day one it was 100 percent adventure, 100 percent of the time: riding and jumping bicycles with friends; canoeing on the mountain runoff ponds; stealing and selling avocadoes and apples for spending money; fishing the mountain streams; digging through the Forest Service dumps for cast-off generator engines and wheels for push- and go-karts; and "borrowing" bulldozers on the weekends with friends. Malcolm learned to operate them from a worker who trained him—and then slept off his hangovers in his truck while Malcolm pushed dirt. "When my mother finally figured out we were joyriding in bulldozers," Malcolm says, "boy, was she mad!"

But it was while walking to school one day that Malcolm's life took a dramatic turn. He spied an old Powell scooter carcass in a driveway and immediately wanted to make it run. It wasn't about riding—just piecing the puzzle together, making it work again, Malcolm's years building go-karts and push-karts lighting his desire to see how things worked. Unfortunately, the Powell's owner didn't want to sell, and 13-year-old Malcolm was crushed. But Betty took pity, buying him a Lambretta scooter—a 125cc two-stroke from a local dealer.

"That Lambretta changed my life," Malcolm remembers with a grin. "It gave me freedom to roam, sure, but also that wonderful feeling of adventure and excitement every new motorcyclist feels. I went all over the place on that thing, usually with my buddy John Moreland, who had a 150cc Lambretta. We raced each other everywhere we went, on the trails, through the orchards, and on the fire roads. We had a ball and probably rode every single day for two straight years."

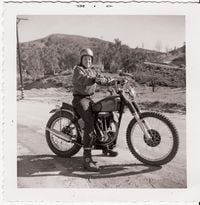

Malcolm and John made their scooters as dirt-worthy as possible, even screwing football cleats into the tires for better traction. But by the end of the second year of Lambretta ownership, the desire for a real motorcycle began to percolate. And on the way to high school one day, Malcolm found the perfect thing: a well-used Matchless 500 single, chained to a light pole outside the owner's home, with a price of $175.

"I had to have that Matchless," Malcolm says. "Just had to. It was so cool, a real motorcycle. I sold the Lambretta and made the deal to buy the Matchless in about two days, worrying the whole time someone would buy it out from under me! What I remember most was the big thump; every time the piston moved, the bike moved. I loved that."

Suddenly, Malcolm's world opened up. Riding to Big Bear or Lake Arrowhead or the high desert was a stretch on the scooter but not on the Matchless. And Malcolm made the most of his expanded range, riding as far and often as he could before and after school, his suddenly plummeting grades not much of an issue in his mind. "Schoolwork just wasn't a priority," he admits.

Riding all those miles wore out an already worn-out motorcycle, and with replacement parts a necessity and money tight, Malcolm began rummaging through the trash bins of a local dealer named Rush "Pappy" Mott, who owned a shop in San Bernardino. "Pappy caught me scrounging for plugs and sprockets a few times," Malcolm says, "and finally offered me a job. 'You're always here,' he told me, 'so you might as well help us clean up.'"

Malcolm learned plenty at Mott's: mechanical stuff, the basics of business, how to assemble 10 Honda Cubs in just a couple of hours (and earn more money than the line mechanics!). Malcolm learned a little about racing, too, from George French, who assembled race engines for the shop's sponsored rider, Jack Thurman. Over time, with Malcolm riding better and better, French convinced Malcolm to try racing on one of Thurman's 600cc Typhoon racebikes. Malcolm agreed, entered his first race at nearby Console Springs, and finished third.

Malcolm's second race was more exciting. "It was a cross-country out in the badlands. To win, I knew I needed to ride wide open all the time, so at the start I basically didn't slow down for turn one—and took out five or six riders when I crashed. I was at the bottom of this big pileup, and I clearly remember seeing a chain and sprocket spinning just inches from my face—quite a sight when you're wearing an open-face helmet. I crashed a lot that day, six or eight times, probably. I'd catch up, crash, start from behind, catch up again—and crash again. But I still did pretty well, finishing second.

"On the way home, I remember thinking, 'If I was on the ground all that time and still able to get second, all I need to do is not crash, and I'll likely win.'"

It worked. Malcolm won his third race and took the first steps to becoming known as a local hot-shoe.

"You had to have a pro license to run the AMA series, and you had to be 18 to get one," Malcolm recalls. "So the minute I turned 18 in March of 1959, I got my pro license, and a week or so later entered a TT at DeAnza, an oiled-dirt oval and TT track upon which legendary Ascot Park was modeled. There were a bunch of my heroes there that day, Thurman, Dick Hamer, and others. But I got second anyway and really felt I had a future in motorcycle racing."

The very next day Malcolm went riding with some buddies. On the way back, one of them—Mike Christensen—didn't show up when they stopped after a particular section, so Malcolm went back to see what was what. Just as Malcolm crested a jump across a fast trail, Christensen came ripping by and slammed into Malcolm at a 90-degree angle, shattering his left leg and bending his Matchless nearly in half. They couldn't have done it more thoroughly had they planned it.

Malcolm flew into a tree and hung there for a few minutes until the shock wore off. When he looked down, he saw the underside of a boot lying on his chest. "Mike," he said to Christensen, who was standing unhurt—and unseen by Malcolm—on the trail below the tree, "can you get your leg off my chest please? It's starting to hurt."

"Malcolm," Christensen said, "that's not my leg. It's yours."

Malcolm Smith's good luck, it seemed, had finally run out.

Look for Malcolm! The Autobiography to be available in the first quarter of 2014. For more information, visit themalcolmbook.com. Also look for additional excerpts in future issues of Motorcyclist.

PHOTOS: Malcolm Smith archives & Ari Michelson

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)