The image of the American biker is reeling—if by "biker" we mean that tatted-out, leathered-up Harley-Davidson rider lampooned in South Park's "The F-word" episode. He's about as passé as the old Clone that my young gay friends like to make fun of—you know, that tatted-out, leathered-up homo-dinosaur that still hangs out at the dive bars on Christopher Street or cruises the Castro in his handlebar moustache and tight, boot-cut Levis. The Clone is as hopelessly outré as the custom chopper he may (or may not) ride.

Those two old warhorses—the Hog and the Clone—have more in common than you might think, bound by the same codes of a once potent but now defunct blue-collar masculinity. Contemporary motorcycle culture in America dates from World War II, when returning flyboys, sailors and infantrymen set up the first motorcycle clubs (M.C.’s) to keep the rush of military service alive. It was a brotherhood built on passion for riding and racing, and while it may be uncomfortable for some to consider, the homosocial elements of biking were there right from the beginning.

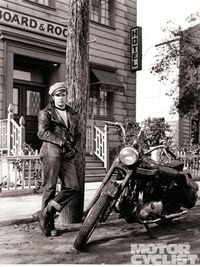

Like many sub-cultural movements, this one began in California, where two rival gangs, The 13 Rebels M.C. and The Boozefighters, squared off in a legendary battle that inspired the Hollywood movie with Marlon Brando and Lee Marvin. With The Wild One's mainstream success, underground motorcycle culture went wide. Life Magazine published photographs direct from the set—creating a buzz and boom in the sale of Schott Perfecto motorcycle jackets, logo T-shirts and biker memorabilia. The "outlaw" masculinity of the clubs—featuring the strict exclusion of women, rowdy hazing rituals and an unadulterated worship of brotherhood—was appealing to many segments of American society—including, of course, homosexuals. The rebel-biker stance mirrored homosexuals' own outsider status in conservative 1950s America. Marginalized gays found deep meaning in the noise, the boots, the leather—"in gleaming jackets trophied with dust," as the great mid-century poet Thom Gunn wrote in On the Move 'Man, You Gotta Go.'

Even today, bikers feel uncomfortable with explicit eroticization of their hobby. When my book, Fast Company, A Memoir of Love, Life and Motorcycles in Italy came out, I received hundreds of letters of protest. "Why did you have to ruin a perfectly good motorcycle book with your perverted sex life? Couldn't you just write about the business of bikes?" A more upbeat e-mail went: "Don't worry, David, I read right past the chapter about your skinhead boyfriend to get to the good stuff—the stuff about engines!" Apparently, motorcyclists prefer their sexual orientation unspoken.

We are supposed to be big boys now. The average age of the American biker is nearing 50. “The bike” is everywhere—in Hollywood films, on television, the stuff of comedy. We have made tremendous inroads to the mainstream. So have gays and lesbians. But something has been lost along the way: our ability to celebrate real outsiders. As we rush to conform and laugh (along with everyone else) at the superannuated image of the Hog, we forget the pride we once had for the rebel in ourselves.

Call me nostalgic, but I still believe that any time a biker—any make, any model—puts on a crash helmet and lowers his visor, he starts to dream. To push oneself to the limit, to break out of society’s expectations of the _bourgeois _self —this is the stuff of adventure, better than any Hollywood blockbuster. I am convinced that when the motorcycling family finally embraces the “other” within our midst—when we celebrate difference—we will begin to attract the next generation of young American enthusiasts we so desperately need. Riding is much more than horsepower and testosterone. It’s a test of personal strength and commitment to comradeship. If only more motorcycle enthusiasts today had the courage of dykes on bikes and fags on Vespas…

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)