Rather than enjoying the holiday with my family and friends, I spent last Christmas in the basement of my parents' house on Cape Cod. That trip was my only opportunity to disassemble and ship my father Todd's vintage Honda CB350 racebike to California in time for the AHRMA National at Willow Springs in April.

The bike had been mothballed for nearly a decade; dad last rode it to victory at Daytona in 1999. His grid positions and jetting notes were still scribbled on the tank in black magic marker. Although the TSA was suspicious, the megaphones, headers, fork and shocks flew back to Los Angeles with me as carry-on luggage. UPS took care of the rest. I was finally going to put dad's racebike back into action, and fulfill my dream of riding a "Henning Honda."

Dad initially raced modern bikes, but with a wife, three kids and a mortgage, he couldn't afford to buy the latest model every other year. So he turned his attention to vintage racing, where competitors campaign the same machines year after year, allowing time for refinement rather than regular replacement. Honda's 350cc and 450cc twins were plentiful and cheap, and he knew they had untapped potential.

Dad started by prepping the bikes with existing go-fast parts, but dissatisfied he began designing and developing his own. He poured himself into the project. Years of late nights in the shop and long hours on the dyno paid off: Dad's engines became almost unbeatable. His hand-built Hondas (once referred to acerbically as "junkyard dogs" by a competitor) defied the odds and consistently beat exotic, high-dollar, former factory racebikes. Two decades later, Todd Henning Racing components are still sought after for their unmatched performance and reliability.

Through simple Pavlovian conditioning, I was imbued with a love for motorcycles. As a kid I went with dad to most of his races and absolutely loved it. Several times a year he would bail me out of school (my teachers approved; they thought it was good experience) to go to places like Sears Point, Daytona, Willow Springs and Roebling Road. As if road trips and roadraces weren't enough excitement for a youngster, dad always inserted perks like go-karting, canoeing or bungee jumping along the way.

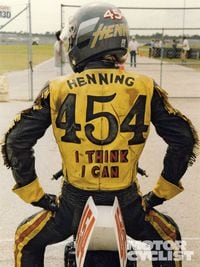

Dad's life philosophy was summarized in four words on the back of his leathers: "I Think I Can." As if through osmosis, that attitude was bequeathed to me at an early age. Even as a kid I was impressed by dad's perseverance, drive and determination. And I aspired to be like him.

The emulation started with a cardboard numberplate on my bicycle. At age 8, I abandoned my Honda Z50 and taught myself to ride my brother's Yamaha YZ80. I had to call dad at work to get an explanation of clutching basics, so I could replicate the howling upshifts he made at the track. After all these years, I'm still hopelessly attracted to naked bikes, a penchant I can only attribute to exposure to dad's unfaired, Sportsman-class machines.

I was still young when my father got hurt. I'd just entered middle school and my new instructors weren't as enthusiastic about my extended absences. So I wasn't there when dad crashed during the last lap of the Premier 500 race at Sears Point, and I'm grateful I wasn't there when the paramedics loaded him into the helicopter, doubtful he would survive the flight to the hospital. The crash ended his racing career, nearly ended his life and cut short his role as a father. His recovery took years, and although his bodily wounds eventually healed, the damage to his brain is permanent and will inhibit him for the rest of his life.

Fast forward 10 years. Dad's accident had a dramatic impact on our family, but it didn't stymie my passion for motorcycles. As an adult, the Honda racer had more appeal and significance than ever before. To me, that motorcycle embodied my father's character; it was the lens that had focused his energy. Riding it would be the ultimate way to reconnect with who he was before his accident. It would be my tribute to his racing career and the time we shared enjoying it.

I got the CB350 assembled and started for the first time on a Thursday evening, just 12 hours before practice was scheduled to start for the 14th annual Corsa Moto Classica at Willow Springs, round three of the AHRMA Historic Cup Roadrace Series. Hearing the old twin come to life was exhilarating. This engine is the real deal, complete with one of the last cylinder heads dad ported before his accident. The inscription "01/99 T. Henning" in Dremel-tool script verifies its authenticity.

Practice was overwhelming. Simultaneously trying to adapt to an unfamiliar bike and a new track, I went from pure glee to abject horror on the first lap. I remember dad riding with a casual smoothness; how had he coped with the debilitating vibration, flexing chassis and feeble brakes? Thankfully my nerves deadened and I adjusted to the machine.

It was unspeakably satisfying to know I was riding dad's bike with the same focus I saw in his eyes in his old racing photos. The fact that this race weekend coincided with the 10-year anniversary of his crash made it all the more meaningful.

On the track I was totally isolated inside my head, completely absorbed in the experience and unaware of the other riders around me. In the pits, I was anything but secluded. Word had spread that I was Todd Henning's son, and as a result a steady stream of visitors stopped by, eager to express their respect and admiration for my father and offer their encouragement and support. It was humbling to know that dad's role in the racing community had been so important. As a kid I hadn't picked up on that.

Rolling to the starting line for the Sportsman 350 race was surreal. I was finally going to do this! The grid was pretty small, about 15 bikes, so for the first time I let myself contemplate a respectable finish; maybe even get a trophy for third place. When the flag dropped I launched forward, shooting ahead of the pack. "Oh crap," I thought, "not the holeshot!" I expected the rightful leaders to come blazing by at any moment, but I kept my head down and rode the wheels of the little Honda, sliding the front and then the back as I barreled through the turns. Pulling onto the front straight, the suspense was too much and I had to look back. The pack was just coming out of the last corner, 100 yards behind me! When the checkered flag fell, I'd won by a mile. The ensuing endorphin rush was so strong that I nearly ran off the track on the cool-down lap. I was beside myself with joy!

My second race of the day was Sportsman 500, in which I'd be going up against larger-displacement bikes, including the built CB450 of my friend and former race winner Rick Carmody. I'd gotten lucky in the 350cc race, but there was no doubt in my mind that Ricky was going to kick my ass in this one!

The starter released us and we barreled into Turn 1, Ricky out in front. But the power of the 350 was impressive, and I quickly passed the few riders between us and fell into Ricky's draft. Approaching the end of the front straight, I used his vacuum to slingshot past going into Turn 1. He got around me at the exit of 2, and I repassed him driving out of 6. I couldn't believe it; I actually had a shot at a second win! We fought hard for three more laps, swapping the lead a half-dozen more times before a hasty pass put Ricky wide at the top of Turn 4, out in the marbles. In my peripheral vision I saw his bike pitch sideways and then skid off into the dirt. Instead of being relieved, I was disappointed by his get-off; we were having a great race! We'd gapped the pack by half a lap, so I dialed back the revs on the 40-year-old mill and cruised to my second win of the day.

With two more wins on Sunday, the weekend was emotionally exhausting, and I hoped to accept my trophies and slip away unnoticed for some quiet contemplation. But Cindy Cowell, AHRMA's race director, had other ideas. Her speech was intimate and concise, evoking a wave of applause from the crowd. As the knot grew in my throat, I was glad my eyes were hidden behind sunglasses.

Racing my father's Honda CB350 was the most moving and gratifying experience of my life. And while it felt phenomenal to win, it felt even better to call dad and tell him I'd continued his legacy.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)