Much like Harley-Davidson and Moto Guzzi, Ducati is associated with a single engine design—its signature 90 degree “L-twin.” Save for the V-four-powered MotoGP racebikes, it’s been since the ultra-rare, race-only Supermono single was discontinued in 1995 that the Italian firm has produced anything other than desmodromic-valved V-twins. But this wasn’t always the case. For the three decades prior to 1985, the year Cagiva bought Ducati and decided to focus almost exclusively on the V-twin layout, the company also produced a variety of singles and parallel twins, while the testing department experimented with a wild diversity of engine configurations and designs—most of which have been lost to history and not even displayed in Ducati’s factory museum.

For a few days during the summer of 2007, Australian photographer Phil Aynsley was offered the rare and remarkable opportunity to visit the test-department archives and photograph some of the surviving prototypes. The variety is remarkable—inline triples, V-fours, supercharged V-twins, fan-cooled singles, desmodromic V-eights, two-stroke motocross singles, and many other designs that are anathema to our modern notion of Ducati. His photos provide a fascinating and intimate look into the Ducati’s history and offer an alternate vision of what we now consider to be a very tradition-bound company.

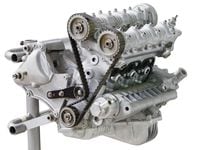

Desmo V-eight Desmodromic valve actuation was cutting-edge technology in the late 1950s, especially in the automotive world. Period metallurgy made the construction of valve springs that would tolerate high-rpm running quite the challenge, so any design that obviated the need for conventional valve springs was strongly considered. And successful. Desmo-valved, straight-eight-powered Mercedes racers won the Formula 1 World Championship in 1954 and '55, leaving other automotive manufacturers scrambling to catch up. Ducati was an early leader in desmodromic technology—its first desmo-valved GP racer appeared in 1956—so when OSCA, a subsidiary of Maserati, set out to develop a desmo-valve race engine they turned to nearby Ducati for assistance.

Famed Ducati engineer Fabio Taglioni, with help from fellow engineer Giorgio Monetti, created this stunning, air-cooled, 1500cc V-eight by grafting eight cylinders from the company’s Grand Prix racing single onto a common crankcase. The top ends were simplified with gear-driven single overhead cams—not triple overhead cams like the GP racer—but otherwise the architecture was very similar. This engine was never entered in competition—OSCA chose to further develop its existing inline-four instead.

350cc Ricardo Triple When Ducati prepared to re-enter Grand Prix racing in the early 1970s after a 10-year absence, it developed two separate engines: a house-built 500cc V-twin and a 350cc inline-triple farmed out to British engineering firm Ricardo. Intended to beat then-dominant MV Agusta triples ridden by Giacomo Agostini, Ricardo engineer Martin Ford-Dunne's design was cutting-edge in every way, incorporating liquid cooling and mechanical fuel injection. Belt-driven dual overhead cams operated four valves per cylinder, with a dry clutch and seven-speed gearbox attached to the back of the engine. The triple was engineered to safely rev as high as 18,250 rpm. The sound was reportedly amazing, with split exhaust ports emptying into six separate, small-diameter headers.

The Ricardo triple was designed in Britain and built in Bologna under the direction of Bruno Tumidei—Taglioni reportedly wanted nothing to do with the inline design. Tumidei hoped the engine would produce 80 horsepower, but early testing was disappointing, resulting in a pathetic 30 bhp. Even after the fuel injection was replaced with more reliable carburetors, output climbed to only 50 bhp. The failed project was summarily scrapped in late 1972.

Two Strokes Like nearly every motorcycle manufacturer in the late '60s and early '70s, Ducati experimented extensively with two-stroke technology as a means to increase production and reduce costs. Two examples of its two-stroke attempts are shown here. Very little is known (or remembered) about the horizontally oriented 50cc single, except that it was apparently built in 1975 and probably intended to power a moped of some sort. The internal cooling fan is a novel technical solution. The 125cc, dual-plug, piston-port-induction single was Ducati's entrée into the booming motocross market, an area where the firm had virtually no experience. A prototype version is shown here; the production version appeared in 1975 first to power the Regolarita, then later in 1977, the more successful Six-Days model. Ducati built its last two-stroke off-road bike in 1979.

V-fours Ever since the Apollo cruiser experiment in the early 1960s, Taglioni was fascinated by V-fours. In 1976, he picked up where the Apollo project left off by designing a liquid-cooled, 90-degree V-four with belt-driven, single overhead cams and two-valve desmo heads. Both 750 and 1000cc versions were built, but the design was shelved after water-cooling was deemed too complicated and cumbersome for production. A third generation V-four design, devised in 1978, consisted of essentially two air-cooled, 500cc Pantah engines siamesed so the front cylinders were separated to allow airflow to reach the rear cylinders—but adequate cooling still remained a problem. The fourth-generation V-four, dating from 1981, incorporated a dry clutch and oil cooling to help keep the rear cylinders at the proper operating temperature. With a quartet of 40mm Dell'Orto carbs, mild cams, and mufflers, this 994cc engine made an impressive 104 bhp on the engine dyno; with an open exhaust and more aggressive cams, it eventually produced 131 bhp. Taglioni saw potential for as much as 150 bhp with further tuning and the addition of fuel injection, but the V-four development budget dried up after Cagiva purchased Ducati and shifted all resources to developing the Desmoquattro engine that would eventually form the foundation for Ducati's present success.

Supercharged Pantah Experiments with forced induction were all the rage in the early '80s, and Ducati wasn't about to be left out. While all four Japanese manufacturers entered production with turbocharged motorcycles, Taglioni—never one to copy another manufacturer—experimented with supercharging instead. Since a supercharger boosts power immediately without any lag like turbo bikes suffer from, Taglioni deemed supercharging a better solution for motorcycle applications.

Starting with a 350cc version of the Pantah V-twin created for the Cagiva Elefant, Taglioni reversed the rear cylinder head and attached a small centrifugal supercharger to the left side of the engine, driven by a belt run directly off the crank. The supercharger fed dual Bing CV carbs. The supercharged motor showed some promise on the test bench in 1985, but by that time the trend for forced induction had already passed and the project was abandoned.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ITNLTIU5QZARHO733XP4EBTNVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZZXJQ6U3FESFPZCBVXKFSUG4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)