The word escaping Don Andre Gardner's lips, I believe, is badonkadonk. That's a hip-hop term for women with large, bodacious behinds, but Gardner-like nearly everyone at Myrtle Beach's Atlantic Beach Bikefest, also known as Black Bike Week-has difficulty with just how much a part of this rally badonkadonk is. "I mean, I come down here looking for a good time, to check out the wild custom bikes and meet some new people. But it seems like the police or somebody doesn't want that good time to happen," said the long-distance trucker who rides a Honda BR1000RR.

Over the past several years, the forces determined to curtail the good times at this 28-year-old rally have involved more than Myrtle's Finest. Sure, Gardner was among the many who received a healthy, $275 moving violation during this year's Memorial Day event. There were also $450 citations dished out to women wearing thong underwear in public. This was considered a brutal blow to the men who travel great distances just to scope on the barely clad women who are one of Black Bike Week's main attractions. But being made to don pants before riding pillion is nothing compared to the less-then-enthusiastic welcome many have experienced here in the past. At the predominantly white Carolina Harley-Davidson Dealer's Association Rally that precedes Black Bike Week, bearded outlaws could be seen wearing T-shirts reading, "This week Bike Week, next week Buck Wheat." Traffic has long been a problem at both rallies, says local resident Tom Riddle, who tries to stay outside of town during the event. "It's bumper-to-bumper loud motorcycles and a major inconvenience to get anywhere. It's not about race, it's about inconvenience," he said.

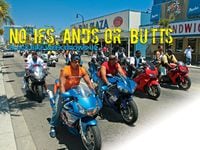

Still, during recent years several local businesses have refused to stay open during Black Bike week, including several hotels. During last year's rally, Myrtle Beach's municipal government thought it a bright idea to enforce a $10 fee for motor-cyclists cruising the Chute, a busy area near Atlantic Beach. Many vendors and riders felt the cover charge to ride on public roads was the last straw in a city unwilling to roll out the welcome mat. "It was like, there's nothing to do, no organized rides or shows and then they want to charge us money just to ride down the street?" Gardner complained. Lucky for sportbike enthusiasts from throughout what many lovingly call "The Dirty South," those and other problems dogging Atlantic Beach Bikefest are fading faster than a bootleg Busta Rhymes T-shirt. Bikefest is finally turning a corner, and around that corner lies cooperation from city government, involvement from a long-absent motorcycle industry and a more family-friendly atmosphere-even if that means an end to badonkadonk as we know it.

Part of the remarkable change visible at this year's Atlantic Beach Bikefest had to do with the Harley-Davidson Motor Company's Department of Minority Affairs. Despite a product that's often associated with cowhide and country music, Harley has been aggressive in courting black and Latino customers. While African-American riders gravitate toward sportbikes in many urban markets, Harley was among the first of the OEMs to include models of color in its catalogs and has actively courted minority owners for dealership franchises. For this year's Bikefest the Milwaukee firm hired Lynn Bonner, a minority outreach specialist, to organize demo rides, hip-hop concerts and a vendor show at Myrtle's Colonial Mall. The Harley-Davidson Rolling History Museum was parked nearby and there were even appearances by African-American celebrity bikers, including rap legend Darryl "DMC" McDaniel from 1980s hip-hoppers Run DMC. The effect was undeniably positive, with organized clubs, custom sportbike enthusiasts and even families hanging out for most of the weekend. Gone were the bawdy "Back Dat Ass Up" and wet T-shirt competitions of years past, replaced by biker gear fashion shows, appearances by stunt rider Jason Britton of Super Bikes! TV fame and an almost innocuous, PG-13 atmosphere. If the sound of Young Joc and 50 Cent hadn't been thumping in the background, this place could have been mistaken for Main Street, Daytona Beach.

That's music to the ears of Bonner. "Harley-Davidson is very committed to reaching out to the minority community, bringing the demo fleet out to African-American events like the National Biker's Round-Up. We saw Atlantic Bike Week as a perfect opportunity to continue that relationship because of the large number of motorcyclists who attend the rally each year and have for some time," she said. Like Daytona's annual Bike Week, this event has been successful in attracting riders of all stripes. Stand on the curb adjacent to Colonial Mall and just about every late-model motorcycle sold in the U.S. will eventually roll on by. Many of the faithful, like Patrick Robinson of Winston, North Carolina, spend most of the year bolting on chrome aftermarket parts and high-performance extras just to cruise Atlantic Beach for this one special week. The high state of tune and eye-searing polish on Robinson's Kawasaki ZX-14R suggest there's more than just cruising going on at Black Bike Week. Late-night clandestine drag races bring plenty of riders to town, though few were interested in revealing just when and where these grudge matches take place. Robinson joked that some serious money changes hands during these races, but for him and thousands of others, a stretched swingarm, a wide rear tire and the appearance of being a fast man on the throttle is enough.

And appearance seems to be what matters most at this event. Despite the heavy fines for rolling in thong underwear, there was plenty of exposed flesh, both male and female, to be seen. A fashion designer would marvel at the riders who coordinated their outfits to match their sportbikes; before coming here, I never knew how natty red Bermuda shorts looked against the backdrop of a DayGlo Honda CBR900RR or how a set of 20-inch spinners can set off a chromed barbecue grill. And for all the sexual overtones and self-conscious profiling, the rally maintains an easy-going, laid-back pace similar to a family reunion, only on motorcycles. Besides a few crashes involving riders leaving the clubs after too much bub, the biggest danger lay in straining your neck muscles watching the opposite sex roll by.

The event dates back to 1980, when a handful of local black riders formed the Carolina Knight Riders Motorcycle Club. Not feeling much love at mainstream biker events in the South, the club extended an invitation to other bikers to join them for a Memorial Day barbecue on Atlantic Beach. "We never expected anything like this to happen, but it just kept getting bigger every year," recalls club President John Glover. "Now the rally is pumping major money into the local economy, so I think everybody, white and black, will eventually get on board." Glover may have ridden in an era when nearly all motorcycle rallies were racially segregated, but the man is far from bitter. "I go to the Harley rally and Bikefest. People like to complain that the Harley rally has more to do, but the difference is that event was created 60 years ago. Give it time and Bikefest will be just that big," he said. Glover's observations, fueled by a quarter-century of observing social changes among bikers in Myrtle Beach, reflect changes in motorcycling across the country. As motorcyclists grow older and more affluent, their purchasing power increases. And whether we're talking Sturgis, Laconia or Myrtle Beach, few chambers of commerce or business organizations are crazy enough to let prejudices get in the way of a fat profit.

Glover's predictions are, in ways, already ringing true. This year, for example, Harley-Davidson wasn't the only manufacturer smart enough to see that green is the only color that matters at Myrtle Beach. Kawasaki brought in an 18-wheeler full of new motorcycles and their multi-time drag-racing champ, Rickey Gadson. Team Green even commissioned Florida's Roaring Toyz to build a tricked-out ZX-10R for the event's custom sportbike show. This year also saw the publication of a glossy, well-organized rally guide to help visitors navigate the Atlantic Beach area. The smell of wood-smoked barbecue was thick in the air as always, while vendors selling chrome parts and wide-tire kits for the ubiquitous Suzuki Hayabusa and Kawasaki ZX-14R were on hand. They shared space with booths doing a brisk trade in T-shirts celebrating a host of urban heroes, from late rapper Tupac Shakur to ghetto entrepreneur Fred Sanford. There were still signs of the old, oversexed Bikefest on display, however. Women waaay too large to be wearing Spandex catsuits were strutting their stuff on stretched and lowered ZX-11s, while the occasional Humvee rolled past, X-rated flicks playing on a rear-mounted flat-screen TV. If anyone here wore protective gear, I must have missed it: The less clothes, the better to be seen seemed to be the order of the (hot, humid) day. The old bromides about Black Bike Week and White Bike Week are also fading, which is another positive sign. There were tens of thousands of white sportbike enthusiasts in attendance this year, many sharing the same club insignias as black riders and the collective love of long, low, big-bore fours adorned with more chrome than Flavor Flav's grill

Mixed in among the old-school black-patch clubs and the young ballers dressed in gold chains and baggy Hilfiger jeans was one truly unexpected sight: Myrtle Beach's home-grown Welcome Teams had taken to the streets, handing out maps, damp towels and cold bottles of water. These mixed-race crews of mostly older residents had decided, on their own, to welcome these loud, half-clothed visitors regardless of what their neighbors thought. "This is the best Black Bike Week I've been to yet," said Patrick Robinson when we caught up with him again. "I love the fact that they've brought this many people, young and old, sportbike and cruiser, all different clubs and races together, and there's no trouble jumpin' off. People said this couldn't be done." True dat.

This year's event was not the first attempt to clean up Atlantic Beach Bikefest. In 2004, the National Association of Black Bikers, a nationwide group headed by Maryland native Keith Hyman, started a three-year run, organizing fashion shows and industry events. Hyman was pleased to pass the torch on to bigger companies, as he said years of negative press may have permanently affected Bikefest. "Like a lot of people, I'm glad to see so much corporate involvement, but gone are the days when there were half a million bikers here for the weekend. The streets were just tire-to-tire thick with bikes and it took four hours just to ride through Atlantic Beach. But after people are made to feel unwelcome for so long, they just tend to go to other places with their money," he said. Hyman, who rides a Kawasaki ZX-9R, also believes the well-publicized, ahem, crackdown on thong-wearing sportbike passengers will affect attendance numbers. "This is a beach. Nobody is supposed to be in a parka or a snowsuit here. This is a very young crowd that is open-minded about showing off their bodies and, let's be honest, to a great many men and women, that's an attraction. The men come to meet ladies and the women love the fast bikes. How somebody decided that's something worth arresting somebody for, I don't know," he said. Something tells me there will be fewer arrests as Black Bike Week continues to clean up its act. One sign of the changing times was the first organized (read: closed course) drag races staged by the Carolina Knight Riders, which should prove a steady draw for the straight-line crowd. And if everybody can keep their pants on, the crowds may start to return.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)