When I hear about some guy who’s had the same motorcycle for 40 years, I’m envious. That’s real commitment, especially in the face of the relentless parade of newer, faster, better bikes that must have tempted him during all those years. But while he missed out on surfing the wave of motorcycle technology, he also probably doesn’t sit around like I do sometimes, thinking about the bikes I’ve owned, then sold, and now regret selling, like these…

Why I bought it: How could I not? The first time I saw it was in 1979, on the showroom floor of TT Motors, a Triumph-Ducati dealer in Berkeley, California. It stood out among the Bonnevilles and Daytonas like Morgan Fairchild (the Megan Fox of her day) at a Weight Watchers meeting. It was breaking the speed limit just sitting there. Every other bike in the place looked like farm equipment. My head never even had a say in it––my heart wrote the check.

Why I sold it: The honeymoon was short. It had the best engine I'd ever ridden, and the worst everything else––a backbreaking riding position, wooden suspension, the turning radius of a school bus, infernally complex and finicky desmo valves (adjust the exhaust valve on the front cylinder a few times and then tell me I'm wrong for hating them), and cast-iron brake rotors that developed a thin coating of rust seemingly overnight.

After a while I realized I had bought it mainly because everyone said I should. I caught someone else’s enthusiasm like a cold, what Mark Twain once called “getting drunk on the smell of someone else’s cork.” I decided a hard-edged Italian sportbike wasn’t really what I wanted just then, if ever. (So far, “ever” is still the right word.) Fortunately a lot of other people did, and one of them took the Duck off my hands.

Why I wish I hadn't sold it: For all the grief it put me through, it was a magnificent beast to ride in short bursts, until the adrenalin wore off and the fatigue set in. It made a sublime noise, like God clearing his throat, and torque poured out of the engine like water over Niagara. I owned it during the peak of my Sunday Morning Ride years, and in my memory it's inseparable from the cold-sweat thrill of booming along a narrow strip of asphalt flanked with rows of trees barely visible in the fog, or hustling through the corners of a road clinging to a cliff high above the Pacific Ocean head-butting house-sized rocks below. If I had it today I'd probably ride it only once a week, on Sundays. But oh, what Sundays they would be.

Why I bought it: In the September 1985 issue of Cycle Guide we tested a gray-market Honda NS400R two-stroke triple and ran companion pieces on several other 400cc Hondas, including the 1975 CB400F owned by editor Charlie Everitt. A month after that issue came out we got a letter (no email back then) from a reader who said he had six CB400Fs, and would any of us be interested in buying one or more of them for $500 each?

The next weekend I threw a ramp in the CG van and drove to the man’s house in the Bay Area. When the garage door rolled up there were indeed six CB400Fs, five red and one blue, all showroom perfect, none showing more than 1,100 miles. He had bought one when it first came out and liked it. Someone convinced him Honda planned to drop them after just one year (in fact they were made through 1977) so he bought five more in case they appreciated. He rode them just often enough to keep the batteries up and the carbs clean, but they didn’t increase in value, and he was getting on in years so he decided to sell them. I picked out a red one for me and a blue one for a friend and took them back to L.A.

Why I sold it: I had no history with the CB400F, as Charlie had, but I'd heard people talking about them for years, raving about the sinuous four-into-one exhaust and the crisp handling and the free-revving engine. It was the smelling-the-cork problem all over again. Its real-world performance was at odds with its reputation. It was a pleasant enough little thing, and earned compliments wherever I rode it, but it was hardly the stuff of legend; it wallowed in corners, bounced on its primitive suspension like a bulldog on a trampoline, and took all afternoon to reach redline.

Its pristine condition was a liability, too, after I moved north and took the CB400F with me to a place where they grow frost heaves, potholes, and “sunken grades” for export to the third world. It was my fair-weather ride in a part of the country where fair weather can be scarce, so it logged more time in my basement under a cover than on the road.

In 2006 I was in a car crash that required a couple of operations and a long stint in a cast to repair my shattered wrist. Paid medical leave is not typically a benefit of a freelance writing career, and with the bills piling up while I healed, I reluctantly sold the CB400F to one of my editors, who still has it.

Why I wish I hadn't sold it: I know now that I was harder on the little Honda than I should have been. I wanted it to be something it wasn't––a modern motorcycle––and condemned it because it hadn't progressed along with my expectations (see: presentism). What I failed to recognize at the time is that it was an expression of the design philosophy that made Honda a worldwide player in the motorcycle industry, and set the bar for just about everyone else to follow. Even today it's the kind of bike I can't walk by without pausing to check it out, and each time I see something else to like about it. And if it's no longer as fast or as nimble as it used to be, well, neither am I.

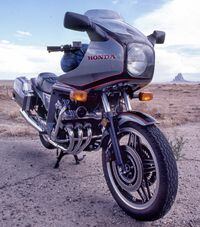

Why I bought it: When I worked at Cycle Guide in Torrance, California, we occasionally had dinner with some people from American Honda's HQ in nearby Gardena. During one of our get-togethers I mentioned I had a jones for a six-cylinder CBX, not the naked early model, but the '81-'82 sport-tourer variant. One of the Honda people mentioned there was an old, dusty '82 in the back of the warehouse she walked through every day to get to her office, and would I like her to see if Honda would sell it to me? I would very much.

It had originally been signed out to a district sales rep who rode it to his dealer calls. When he turned it in for something newer, it was passed on to Honda’s service center and used to train new mechanics, who stripped it down to nuts and bolts and put it back together at least six times under the watchful eye of senior instructors. When I went to Gardena to see it, it had a near-dead battery, two flat tires, and a price tag no sane motorcyclist could resist, so I took it home.

Why I sold it: I brought it with me when I moved to the Pacific Northwest. I didn't have a garage at my first house so I kept it in a storage locker across town. But I couldn't ride it past 5 p.m. or I'd get locked out for the night. Between the hassle of riding it, and the salty coastal air nibbling away at the shiny bits, I used it less and less. In a more suitable environment––one, say, where I had a garage––it would have been pampered and ridden almost daily. As things stood, it was dying a slow death.

I might have held onto the CBX until my circumstances changed, but I badly miscalculated my tax liability one year and sold it to a Japanese man who owned a helicopter company back home. His English was barely comprehensible but the stack of benjamins he offered me spoke loud and clear. I like to think he took it back to its ancestral land in one of his choppers and restored it to its former glory.

Why I wish I hadn't sold it: If you know anything about motorcycles you know the six-cylinder engine was one for the ages. But as a sport-tourer the CBX wasn't as memorable. The hard bags were barely large enough to hold a big idea, the fairing was scarily efficient at funneling air directly at places you didn't want it to, and after an hour on the awful seat I felt like James Bond in that scene in Casino Royale where he's tied to the wicker chair with the bottom cut out of it.

But the CBX was, and probably still is, one of the most extravagant two-wheeled devices ever made for the sole purpose of moving a person or two from point A to point B. It’s an audacious and in-your-face celebration of excess, one of the best examples of the because-we-can philosophy that occasionally prompts Honda to take off its tie, roll up its sleeves, and build landmark bikes like the CB450, the CX500 Turbo, and the VF750. A photo of a pearl white ’82 on the interwebs still makes me stop and admire it.

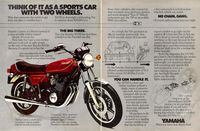

Why I bought it: Like a drunk who wakes up from a year-long bender and repents of his sins by taking the cloth, I wanted something practical and undemanding after the heady days on the Ducati, a palate cleanser to get the bitter taste of too much exotica out of my mouth. I found it in a shaft-drive Yamaha XS750 triple I got from a part-time SCCA concours judge.

As befitted its former owner’s avocation, the bike was as spotless as Ray Charles’ driving record. The three-cylinder engine had a captivating growl, and the flat seat and low handlebar fit me perfectly. With a tank bag and throw-over saddlebags it was the perfect weekender, and I rode it up and down the Pacific Coast Highway until I knew every corner by name, rank, and serial number. There was little that bike couldn’t do, and little that I didn’t do on it. The only negative I can remember is the number-three cylinder’s points were a bitch to adjust; the timing light strobed erratically, like a disco ball, but just on that one jug. Otherwise it was about as capable and appealing a bike as I’ve ever owned.

Why I sold it: I was working at a Honda dealer at the time, and the occasional dirty look from the owner as I parked my Yamaha in the lot didn't bother me. But when a lightly used Honda CB900F appeared on the showroom floor, something snapped. It was the head-versus-heart thing all over again, with the hot-eyed CB900F making me wish the button-down XS750 had more…well, more everything. I sold the Yamaha to a friend of a friend, who sold it to a pizza cook in San Francisco named Leonardo, who ran it out of oil, then offered to sell it back to me with a seized engine for the same price he'd paid for it. I was tempted, but passed.

Why I wish I hadn't sold it: You know when you're sitting round with your bench-racing buddies talking about the ideal motorcycle, the one you'd buy in a heartbeat if some manufacturer would only build it? I always come up with an air-cooled 750cc triple with shaft drive, a broad, flat seat, and a low handlebar. Of all the bikes I've ridden and later sold, this is the one that suited my temperament and riding style the best.

Why I bought it: Yamaha's first water-cooled 250cc production racer was as close to a factory bike as a cash-strapped club racer could get in 1974. For around $1,500, plus a couple of hundred more for a fairing, I replaced the parts-bin TD2B I'd been holding together with zip-ties and Loctite for the last two seasons with a well-built, reliable, and deadly serious mount.

The entire time I raced it, it was as reliable as a hammer. It shrugged off my ten-thumbed attempts to make it faster and lighter, and always got me to the finish line. Over the next three-and-a-bit seasons I took it to Daytona, Laguna Seca, Sears Point, and Ontario Motor Speedway on an odyssey during which I saw parts of the country I’d never seen, started and ended a torrid and geographically inadvisable relationship with a woman from the east coast I’d met in Daytona, and accumulated a lifetime of tall tales to shamelessly embellish and inflict on younger riders in my later years.

Why I sold it: I finally accepted that six-foot-tall, 170-pound me was never going to keep up with the snarling pack of ferocious midgets that populated the AMA Novice class. I let my license lapse and then had the spectacularly stupid idea of turning the TZ into a streetbike.

The TZ’s engine was based on the popular R5/DS7/RD250/350 series, and a lot of the parts were interchangeable. I bolted on reed-valve cylinders and pistons, cobbled up some expansion chambers with laughably ineffective silencers, and wired it for a battery and a charging system. I botched that last job and only discovered it when the bike ran out of spark on a two-lane country road about 40 miles from home. While a buddy went back for a pickup I lay on the grass and decided it was time to let the TZ go, mostly because of the unholy mess I’d made of it trying to realize a hare-brained dream.

Why I wish I hadn't sold it: The TZ was like an old dog; we had a history, that bike and me. I worked on every piece of it myself except the crankshaft, and could probably still take the engine apart in less than an hour just from memory. Classic racebikes like the TZ don't look like the cyborgs of today, made of unobtanium, crammed with black boxes, and rolling on tires as wide as the ones on my Miata. You can look at an old racebike from the side and see everything on it in a single glance; the most exotic material on the whole thing is aluminum. Today the TZ would be in my living room on a low platform with spotlights above it. But the last stock unrestored TZ250A I saw was listed at $12,000, so some old photos on my bulletin board will have to do.

Editor's note: Tell us your story! Send us text ("Why You Bought It, Why You Sold It, Why You Wished You Still Had It") and photos of the bike and if we use your submission, we'll send you a magnificent Motorcyclist t-shirt and some other random swag. Email us at mcmail@bonniercorp.com

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HFT7ZG7MAPEXLEGYKFZE75H2KE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/C27PWVRTIW445BMJKH7JIPZAXQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)