Chevrolet Corvette Z06. Ford GT. Dodge Viper. The USA has moved on from building simply fast straight-line sleds to creating genuinely world-class high-performance cars—truly supercars in their own right. But where is the two-wheeled equivalent, the American superbike? It’s a question that’s been asked for years. Creeping like a fog across dealership floors, lingering over bike-night crowds, and gnawing at race teams. Rumors float, designs are patented, and a few bikes are built over the years. But there’s never been a legitimate mass-produced American superbike.

Until now.

Erik Buell Racing's 1190RX is the real deal—a high-horsepower machine meant to excel on the track and awe on the street. It costs $18,995, has a beast of an engine, and it's handmade in the heartland. (UPDATE: EBR is running a "spring clearance event" on 2014 1190RX and streetfighter SX models. The discount is $2,000 on the SX and $4,000 on the RX, making both $14,995.) The RX is almost overflowing with ingenuity and technology, and it's all aimed at turning fast laps. Zack Courts vetted the RX on the track at Jennings GP in Florida (see "Prescription Filled," here), where he was impressed with the bike's poise, power, and traction-control system. That first taste left open one critical question: How does such a purposeful machine perform on the street, where the majority of buyers are bound to ride it most? That's why we spent a couple of weeks in the saddle, commuting on the freeways and carving up SoCal's many legendary canyon roads—living with the bike like you would—to find out.

Stylistically, EBR’s effort doesn’t much resemble its competition from Europe and Japan, but the RX’s ergos are fairly standard for the class with wide, flat clip-ons and a firm, thinly padded seat. It’s a comfortable enough riding position, aggressive but not fully committed, and the reach to the bars is relatively short so you can sit fairly upright. In that position, however, the color TFT dash is partially obscured by the windscreen and your torso is out in the breeze at speed. EBR describes the 1190RX as having a “race cockpit,” and it’s true in a narrow sense—the only way to fully see the dash or get behind the low windscreen is to tuck in like a racer.

The sense of seriousness extends to the EBR’s V-twin engine, which bangs and quakes off idle, begins to smooth out and growl fiercely in the midrange, and positively thunders when you roll the throttle to the stop. There’s never any doubt that you’re straddling a tremendous engine. As you might expect from a 1,190cc V-twin there’s power everywhere, but things don’t get serious until the 6,000 rpm mark, when the engine rolls into the thick of the torque curve. That’s about when vibration creeps into the grips too.

The gearbox is flawless, but it's hindered by a heavy clutch that only Popeye could love. (UPDATE: EBR says the current-production bikes have a revised master cylinder that greatly reduces lever effort.) Despite the effort required, the clutch engages progressively and rocket starts are a cinch. First gear is short and offers impressive acceleration, but there's a large jump to second. In particularly tight canyons, neither gear seemed like the right fit, though it's worth pointing out that unless you're bent on getting to the summit first, you can stick the bike in fourth and lug the engine and still haul serious tail. There's a vacuum-operated slipper clutch that works well in the upper gears, but the back-torque spike when shifting from second to first sometimes set the back wheel to hopping.

Engine heat is omnipresent, which you can’t miss during hot-weather rides. Truth is, the EBR radiates heat from all surfaces, but your right leg will suffer the most, as it has both a radiator fan and an anaconda of a header pipe to contend with. The fans run almost constantly, switching on moments after you start the bike and remaining on even after you’ve removed the key from the ignition. No doubt there was an engineering desire to keep the bike light, and perhaps that influenced cooling-system design, but this bike’s behavior is pretty extreme.

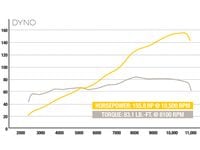

You can't have internal combustion without lots of heat, and the EBR is sucking in mixture 595cc at a time, compressing it down to less than a thirteenth of its original volume and exploding it with enough effect to put 155.8 hp to the ground at 10,500 rpm. That horsepower figure is right on par with the competition—according to our dyno records, that's more than the KTM RC8 R and Ducati Panigale 1199 twins and Aprilia's RSV4 V-4 but less than the BMW S1000RR, Kawasaki ZX-10R, and MV Agusta F4RR inline-fours. Plus, this V-twin shines in terms of torque. The EBR slams 83.1 pound-feet to the pavement at 8,100 rpm, out-stomping every production superbike we've tested since the pre-superquadro Ducati 1198, which made an additional 1.5 pound-feet—albeit without the EBR's top-end rush. So EBR's big sales pitch about the 1190's combination of lap-time-boosting top end and street-crucial torque is not just hollow posturing.

At 451 pounds with its frame spars full (they double as the fuel tank), the EBR fits the bill in terms of weight too. It’s 14 pounds lighter than an Aprilia RSV4 Factory and 20 pounds heavier than the up-spec, $29,995 Ducati 1199 Panigale R. The bike feels lighter than its curb weight suggests, though, no doubt thanks to EBR’s focus on mass centralization. Initial steering input is light and handling is superb. The EBR tips in off vertical quickly and slices a confident line through any kind of corner, feeling balanced and stable. Front-end feedback is tremendous, encouraging greater lean angle and more corner speed. That big 386mm perimeter front brake has a gentle bite that’s appreciated on the street and is backed up by rear-tire-lifting power, though braking force doesn’t feel directly proportional to lever effort.

The suspension—fully adjustable Showa parts front and rear—is distinctly firm but still compliant over smaller bumps and sharp edges. Several of the roads we strafed were rippled and cracked, and while the chassis communicated everything the tires rolled over, none of the inputs had any effect on trajectory.

Aaron Frank described the identically suspended naked SX's ride quality as harsh in his First Ride (see "1190SX First Ride" here), but the riders who tested the RX found the suspension to be surprisingly compliant for the amount of support it offers under hard braking and full-throttle acceleration. Two important variables to consider: First, Aaron rode the SX in Wisconsin, and we rode the RX in California. Second, Aaron's own 155-pound wet weight is light for the baseline setup on both bikes—they're aimed at riders between 165 and 190 pounds. We didn't note the same harshness on the RX, but we also outweigh Aaron by enough to matter. There's ample adjustment on either side of the baseline settings, and pulling out a full turn of compression damping at both ends softened the bike up appreciably, making freeway drones more tolerable.

Traction control is primarily a safety net on the street, and we preferred riding with the RX’s system off since the rear Pirelli offers so much grip and the motor is so tractable. There are 20 levels of intervention, and anything above level five (the lower the number, the less intervention) hampers acceleration on dry, clean roads. The higher levels are clearly intended for cold and/or wet conditions or other times when there’s little grip—such as when the bike you’re launching down the quarter mile begins belching oil on the rear tire.

How’s that? Our bike wept oil from the right side of the engine while strapped to the dyno and later spurted lubricant on the dragstrip from the same area of the engine, forcing us to abandon testing after just three runs. (Hence the slow ET.) Disappointing, sure, but that wasn’t the only issue we had with the RX. During the 600 or so miles we spent on it, the RX’s “Engine Code Event” light illuminated four times (all the errors were benign and cleared via the intuitive dash interface), and everyone complained of excess throttle play (the inline adjuster was already maxed out).

Those issues are likely limited to our first testbike—a replacement RX delivered just as we were going to press, plus the testbike assigned to Cycle World, had no such problems. We're obliged to report our findings but hopeful that these problems are isolated to one particular machine. But there are other gripes that are just part of the design. Like the frustration of gaining access to the dash buttons that reset the tripmeter and adjust TC. As Zack so elegantly put it, "I feel like a veterinarian helping a cow to give birth trying to get my whole arm in under the bubble." Bar-mounted switches would be great. And how about a fuel gauge and engine-temperature readout?

Then there’s the maintenance schedule: EBR wants owners to have the clearances on the titanium valves checked every 6,200 miles, twice as often as on most other superbikes. Fit and finish are a step or two behind the leaders, even if the RX is light-years ahead of offerings from the previous Erik Buell venture.

Those shortcomings are really frustrating because the RX goes, turns, and stops as well as most superbikes, and we want a viable American version as much as anyone. EBR worked hard to make the 1190RX competitive in terms of price, performance, and weight, and the company can be proud of the 1190RX. We take solace in the likelihood that V2.0 will be even better as EBR continues to develop the platform. So, here’s to the arrival of the American superbike. At long last.

ZACK COURTS

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

AGE: 31

HEIGHT: 6'2"

WEIGHT: 185 lb.

INSEAM: 34 in.

Get as patriotic or as wrapped up in the story of Erik Buell and his team as you like; when you boil it down this is a good motorcycle. Sure, there is room for improvement. Fit and finish doesn’t stack up to the Euro brands’ offerings, and with the EBR’s price tag that’s the most direct competition. There are a few odd-fitting panels and wires routed questionably, and the dash is a little frustrating to use. Would I still buy or recommend an RSV4 or an S1000RR? Yeah, sorry, I would. But the foundation at EBR is there, and it’s enough to get excited about. I hate to say it, but I already can’t wait for 1190RX 2.0 because when they iron out the wrinkles this is going to be a truly world-class superbike.

MARC COOK

EDITOR IN CHIEF

AGE: 51

HEIGHT: 5'9"

WEIGHT: 185 lb.

INSEAM: 32 in.

We all imagine what it would be like to take a serious racebike out on the street—especially the part about sampling a truly powerful, purpose-tuned engine. It just doesn’t seem like it should be legal. Well, it is. The 1190RX’s engine idles unevenly, emits percussive knocks as signs of impatience while you wait for the light, and then comes alive in a huge rush of torque to a soundtrack not unlike dragging a two-ton magnet through the All-Clad factory. It is sumptuously mechanical, with abundant gear whine and prominent combustion-event vibration. It’s raw...and utterly captivating. That it’s bolted to a vehicle with a license plate and warranty is simply amazing.

ERGO It's a sportbike, but it's a reasonably comfy one. A big part of that is the short reach to the bars—that 28-inch stretch is an inch less than most other bikes in the class. The seat is thinly padded but notably broad wind protection is adequate for the category, and legroom is adjustable. If only the engine didn't bake your bottom and vibrate your wrists so sadistically.

DYNO The 1190RX engine combines bracing peak horsepower with an incredible spread of torque. There's more than 60 pound-feet of it from 3,500 rpm on and more than 80 pound-feet for more than 2,000 rpm. Other twins in the category—the Panigale and RC8 R—breach the 80 pound-feet line but only briefly.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OPVQ7R4EFNCLRDPSQT4FBZCS2A.jpg)