The words “genius” and “tragedy” are often misused, but it can be said without a doubt that motorcycle designer John Britten was an undisputed engineering genius, and that his death in 1995 of skin cancer at age 45 was a significant tragedy for the motorcycling world. The brilliant bikes he developed were enough to ensure his enduring status by their technological excellence and avant-garde engineering alone; the fact that they also won major races around the globe, defeating established manufacturers with far greater available resources, only adds to his legend.

That Britten motorcycles were designed and built in faraway Christchurch, on New Zealand’s South Island, enhanced their otherworldly mystique. Operating in such remote isolation, Britten had little choice to do it alone, and his way. Britten suffered a severe reading disability that made book learning laborious, so he learned to trust his intuition and experience more than what some book said was right. (Though he did hold a mechanical engineering degree, eventually completing a four-year night school program.) This was the root of his innovative nature. He used cutting-edge materials, like carbon fiber. He developed his own girder fork, rather than use someone else’s telescopic unit. He dispensed with conventional wisdom entirely, using the engine as a fully stressed chassis member, locating the rear shock behind the front wheel, hiding the radiator under the seat to reduce frontal area, and embracing EFI when the technology was in its infancy. John Britten was an innovator above all else.

After spending his early twenties as a hippie dropout making and selling glass lamps and handmade furniture, Britten joined his father’s business and became one of New Zealand’s leading property developers—and an avid motorcyclist on the side. Already a successful vintage racer, Britten was testing some of his esoteric ideas about chassis design with a Ducati-powered prototype in the mid-’80s when he teamed up with an engineer named Bob Denson, who produced an air-cooled, 60-degree V-twin engine under the Denco name. In 1986, Britten debuted his first eponymous motorcycle, the Denco-powered “Winged Wonder,” known for its distinctive, futuristic bodywork.

The most remarkable aspect of that first Denco-Britten was its chassis—a Kevlar/carbon-fiber monocoque that used the engine as a stressed member, with an under-seat fuel cell and the rear shock mounted horizontally beneath the engine. Inspired by the KZ 7 “Kiwi Magic” America’s Cup sailboat that used similar Kevlar/carbon-fiber construction, and informed by fellow New Zealand designer Steve Roberts’ similarly configured, Suzuki-powered “Plastic Fantastic” TT Formula 1 racer from 1983, Britten’s monocoque design consisted of 26 separate pieces that were bonded together, weighing just more than 26 pounds.

The 1000cc, 120-horsepower Denco twin was fearsomely fast but fragile in competition, inspiring Britten to soon build his own engine. Britten’s design was cutting-edge in every way, utilizing fuel injection, a narrow valve angle and arrow-straight intake tracts. More importantly, it was designed to double as a fully load-bearing structure, giving the designer a completely free hand with the chassis configuration and opening the door to the “frameless” construction that defines the radical Britten V1000 that followed.

Reliability problems prevented that first V1000 from achieving anywhere near its full potential, but instead of giving up, Britten started over with a clean sheet to design and build the “Mark II” version that finally proved the genius of his radical thinking. The eight-valve twin was left mostly as-is, and Britten manufactured all the components in house, save for the pistons and gearbox (sourced from Suzuki). Both 1000cc and 1100cc versions were built, delivering 160- and 171-bhp respectively, far exceeding even the best available performance of the factory Ducatis.

The bulk of Britten’s energy, however, was focused on optimizing the radical chassis. The bike was redesigned completely to be as slim and aerodynamic as possible, with most of the bodywork stripped away to leave the booming engine and proprietary suspension systems in clear view to the world. Up front appeared Britten’s own carbon-fiber girder fork design, similar to the Fior wishbone but with optimized geometry. All the carbon-fiber components, including the monocoque body, fork “blade,” swingarm and even the wheels, were formed using Britten’s unique and now-patented “wet-laying” method.

The first test of the Mark II was far from encouraging—the fork snapped off, with a TV camera on-board no less! Alterations were made to the design, however, and the bike’s potential was apparent during its very first racing outing, at the Daytona Battle of the Twins event in 1992. Despite a cracked cylinder in practice that caused New Zealand-born rider Andrew Stroud to start from the back of the grid, the Britten was soon running at the front and wheelying past Pascal Picotte’s works Ducati on the infield straights, until rain caused the race to be stopped. A flat battery (after the ignition was mistakenly left on during the break) was all that prevented Stroud and Britten from winning that event. The team made up for that mistake by winning the Battle of the Twins round at Assen later that year, followed by second place in the Pro Twins category at Laguna Seca. This was just the beginning of the Britten’s incredible stretch of Twins-racing success.

There was no BOTT race at Daytona in 1993, so instead Britten concentrated on setting a series of World Speed Records, including the 1000cc marks for standing-start quarter-mile, kilometer and mile, as well as the flying mile. When BOTT returned to Daytona in 1994, it was Britten-mounted Stroud standing at the top of the Speedway’s podium—a feat he repeated again in 1996, ‘97 and ‘98. Brittens also dominated the 1994 New Zealand Formula 1 national championship with rider Jason McEwan. True racing success arrived in 1995, when Stroud won the BEARS (British, European and American Racing Series) World Championship rounds at Daytona, Thruxton, Zeltweg, Brands Hatch and Assen, dominating on an international stage. Stephen Briggs, on a customer's Britten, clinched second in the series.

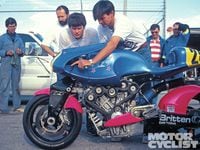

It was a fairytale ending for the eccentric man from Christchurch, and it wasn’t a moment too soon: John Britten passed away just three weeks after Stroud was crowned champion, following a brief battle with melanoma. His death meant the end of several projects under development, including a planned Britten Supermono with a liquid-cooled, six-valve single that used structural carbon-fiber crankcases to produce a roadracer weighing less than 200 lbs., ready to race. As it stands, the Britten Motorcycle Company built just 10 V1000/1100 Mark II motorcycles in their distinctive blue-and-pink livery that was inspired by a piece of decorative glass Britten owned and admired.

John Britten achieved a great deal in his short life. Those fortunate enough to have known him will remember his boyish smile, his shy stammer, his admiration for anything different or unusual, and his uncompromising drive for success. His memory is honored by any avant-garde two-wheeled design done right—especially one that’s proven on the racetrack. MC

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)