It is 1979. Jimmy Carter struggles with a hostage crisis in Iran. Margaret Thatcher is elected prime minister. Sony introduces the Walkman. Pink Floyd releases The Wall. At the end of a tumultuous decade, we stand wondering what the 1980s will bring.

Some of the future is already in view. Honda just launched its 24-valve, six-cylinder CBX. Suzuki's amazing GS750 and GS1000 are better than ever. And Kawasaki's Z1R heads a collection of midsize and open-class KZs packing stunning performance. Kawasaki and Suzuki have clearly and successfully moved on from purveyors of popular, inexpensive two-stroke streetbikes.

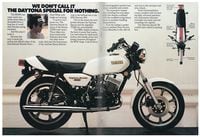

Yamaha has its XS11 four and XS750 triple—following a slightly different path than market-leader Honda—but there's another bike in the 1979 lineup that grabs everyone's attention. Small and white, it features a dramatic blood-red stripe running its length, à la the company's fearsome TZ roadracers. It's a bike no one expects in this day of increasingly restrictive smog laws and the near-total domination of the latest four-strokes.

It is, of course, the RD400F, a 400cc two-stroke known also as the Daytona Special. And it is special indeed.

Amazingly, the Daytona wasn’t simply a previous-year RD400 with a flashy new paint job, which you might expect given the two-stroke streetbike’s seemingly dim future in the US. The Special had been thoroughly and expensively revised, almost as if Yamaha planned to keep it in the lineup for a few more years, stringent smog laws notwithstanding. You don’t drop so many yen on a two-year short-term special.

"It's funny now," says longtime Yamaha product-planning guru Ed Burke, "but we didn't know how long we could keep the RDs going. Every year we'd somehow find a way to keep ahead of [the EPA]. The factory was really good about tweaking the bike every year. We were always back-ordered, and retail sales were phenomenal, in the US, Canada, and overseas. Yamaha wanted to keep it going, as the bike was a mainstay and profitable. Cruisers were the coming thing, but in '78 there was little fruit there, so the company wanted to keep two-stroke streetbikes alive."

And if there’s one thing the RD400F was, it was alive.

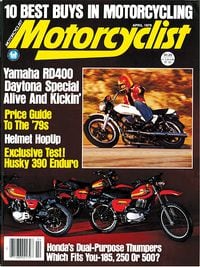

The April 1979 issue of Motorcyclist featured a very young Ken Vreeke strafing a corner in living color. "The Yamaha RD400F is here to tell you the two-stroke is alive and, thanks to a few simple pieces of technology, just as high-strung and speedy as ever. The bike is essentially the same old wheelie-popping, four-stroke humiliating, lightweight, nimble, cocky RD400…" rang the road test.

Cycle summed it up nicely in its June '79 road test: "Innocent-looking, trim, petite, quiet—all of it's a sham: the 400F encourages the unwary to go too fast, accelerate too briskly, stop too hard and wheelie too often. Anyone with the narrowest streak of anti-social behavior will find the RD the perfect conspirator. It is Dennis the Menace on Yokohama tires, and is the most fun street motorcycle currently available for sale."

It's almost as if Yamaha flipped the EPA off and built an RD even quicker than the previous year's version. Cycle again: "Did they do it because they were seriously interested in the 400 as an ongoing profit center, did they do it to show off their technical depth, or did they do it to stick it to Kawasaki and Suzuki, both of whom have folded their two-stroke tents? 'All of those,' reckoned a Yamaha spokesman."

“When we decided to do the Daytona,” Burke says, “we knew it would likely be the last of the air-cooled RDs, as we had liquid-cooled designs in the pipeline. We knew we had to make it special, with added technology, power, functionality, styling, et cetera. We wanted the RD line to go out with a bang and celebrate the many years of R5 and RD successes in the showrooms, on the street, and, of course, on the racetrack. Looking back now, it’s pretty clear we did a decent job. The suspension was good, the frame was stiff, and the engine was really torquey, which made it super nice to ride, and it looked good. It had morphed over the years from a rough-around-the-edges hot rod to a more refined sport motorcycle, although one with serious performance and an attitude to boot.”

The genesis of the RD400F (the “F” designating the year—’79—in Yamaha nomenclature) began, really, with Yamaha’s very first motorcycle, the 125cc YR1 of 1955, which won its class at Mt. Fuji and Mt. Asama, Japan’s two most prestigious races. Twelve years later came the 350cc YR1 twin, a breakthrough machine featuring the horizontally split (and much stronger) crankcases that would help future Yamahas produce the sort of reliable power that would make them Giant Killers on the street and racetracks of the world. R2 and R3 versions appeared in ’68 and ’69, respectively, as did the legendary 350cc TR2 and 250cc TD2 roadracers, which quickly began to dominate.

“The streetbike engines were developed right along with the TR/TD racing engines,” Burke remembers, “so there was a very early racing/street connection between these lines.”

But it was the R5 of 1970 that really opened enthusiasts’ eyes, as it formed the basis for the RD350 and 400s to come, albeit with drum brakes and piston-port induction. The bike was an instant hit and a major step up functionally and aesthetically from Yamaha’s stodgy, ’60s-era 350s. The R5 did it all, from sport machine to commuter to tourer, and it looked great too—sleek and polished and modern. The R5 featured a stiff frame—no surprise, as it was almost exactly the cage found on Yamaha’s TD/TR roadracers.

The RD350 of 1973 was more of the same, with even better power and chassis performance thanks to reed-valve induction and a disc up front. On the street, at the track, and in the pages of the magazines, the RD350 quickly became Yamaha’s performance flagship, a lightweight and nimble sport machine able to slay streetbikes twice its displacement—all while making only about 35 hp. The fact it cost just $800 sweetened the deal, and it’s no wonder Yamaha sold more than 60,000 RD350s during the bike’s three-year run, from ’73 to ’75. Amazing numbers.

America’s bicentennial brought the RD400C, which was quite a bit more than a larger-displacement 350 with alloy wheels and reshaped bodywork. It was a near-total engine and frame redesign, its extra 49cc coming from an 8mm stroke increase, which expanded the bike’s already sweet midrange power. The 400 was some 15 pounds heavier, but its extra midrange and more capable chassis made the weight gain a non-issue, as the bike was easier to ride quickly.

Like the 350, the 400 lasted three years (’76 to ’78), with stiffer smog regs and the rise of brilliant four-strokes like Suzuki’s amazing GS750 threatening to push two-strokes right off the map. But would Yamaha keep at it, especially considering the debut of several new Yamaha four-strokes?

The answer, which came in late ’78 at Yamaha’s annual dealer meeting, was an unmistakable yes in the form of the Daytona Special, a beautiful and (again) heavily revised machine that carried Yamaha’s two-stroke torch proudly while flipping the bird to the EPA by keeping the F-model just under the smog limits.

Engineers did this by taking advantage of the EPA’s test procedure, which measured emissions taken in four different modes—at idle, during acceleration, while cruising, and during deceleration—and averaged the results. Because two-strokes spew a lot of unburned hydrocarbons during decel, engineers figured they could get the bike’s average number below the maximum allowable figure by using clever technology that limited this effluent via a combination of butterfly valves located between the exhaust ports. These valves simply closed off the ports and were powered by a vacuum-operated accumulator, which closed the valves on decel and used a throttle-position vacuum to open them when the rider cranked open the throttle. Small bypass holes in the butterflies kept the engine from being totally strangled at idle and on deceleration.

A Suzuki Ram Air-style single cylinder head also helped by reducing noise and adding extra cooling, which the engineers feared the RD would need given the emissions equipment. A Yamaha spokesman quoted in Motorcyclist dispels that fear: "We thought the exhaust butterflies would raise hell with engine temperature, but it really runs very cool." Other small tweaks came with the Daytona special—a slightly increased compression ratio, taller lower gears, a different piston and ring pack, and new 28mm slide-throttle Mikuni carburetors with a combined linkage to ensure and maintain synchronization.

Although the Daytona made no more horsepower than previous 400s, it was quicker in the quarter mile (high 13s) and easier to ride on a fast, curvy road than its siblings due to its prodigious midrange. “It’s as though the power band was just shifted downward 600 or 700 rpm. Power has improved noticeably below 6,000 rpm, bringing easier getaways and improved roll-on acceleration,” we said way back when. And we were right. Ride a Daytona Special today after a spin on a ’78 RD400 and the difference is obvious.

Chassis changes above and beyond the TZ-esque paint on the sleek new body parts included 1mm-thicker fork tubes, larger brake discs, and redesigned footpegs—held in place by mounts that no longer looped under the exhausts—dramatically increasing cornering clearance. Production racers and aggressive street riders cheered.

“The Daytona was really fun to ride,” Burke says. “It was light and had satisfying acceleration; you could feel it come on the pipe, but the power was very controllable. It handled wonderfully too.”

"If it turns out that the buck stops with F," wrote Cycle's editor Cook Neilson, "that Yamaha will be satisfied with this one great last thumb in the eye of the EPA and hereafter call it quits, then at least the RD series will have ended gloriously, with a bang, a hoot and an irreverent four-gear wheelie right across the bow of the establishment. As a raffish partner in crime it is absolutely damn dead-center perfect."

That Yamaha’s last real hurrah with a US-spec two-stroke was the water-cooled RZ350 should not diminish the RD’s significance as the last of a great series of sportbikes. Ride one, and you’ll realize how the beehive engine note, the ringing of the cylinder fins, the lightness of its form could be so right for a world in transition—one turning to slow-revving, top-heavy four-strokes. But not without a fight.

The 1980s did arrive but did so without an RD400 for American riders. They soon came to miss an amazing motorcycle that was quick, hugely entertaining, and no doubt a touchstone to so many youthful motorcycling adventures. A machine right for its time.

More than merely right. Special.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)