I'd just parked the Honda Hawk GT I was riding and was checking out the bikes parked under the canopy of trees that surrounded the historic old church—the halfway point of the Grand Marshal ride for this year's Riding Into History event near St. Augustine, Florida—when I spied it: the metal-flake orange paint and funky beer can-shaped instrument cluster and taillight that could only belong to one motorcycle, a first-generation Suzuki RE-5 rotary.

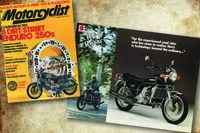

Motorcyclist Editor Cook and I had been talking of a Suzuki rotary story for more than a year, though finding a presentable bike to shoot and ride had proven difficult. Not many were sold (just more than 6,000), and ones in running condition seemed as rare as barn-find sandcast K-zero Hondas.

But here was a seemingly nice one. Only 5,000-some miles, no obvious repainting or overzealous restoration, and since it got here, it ran. Nice.

I found the owner—Todd Haifley—chatting nearby and after introducing myself I asked if the bike would be at the RIH concours the following day. “Yes,” he said. Could I photograph it for a story? “No problem.” And then the biggie: Could I ride it? “Sure thing,” he said. Really nice.

I knew very little about Suzuki's RE-5 rotary at that point. Just two years on the market ('75 and '76) and thusly an obvious sales failure, the RE-5 is a retro bike that seems to live on the margins of enthusiasts' consciousness. "RE-5, eh? Hmm… Suzuki, right? Didn't Norton or Hercules build them too?"

The roots of the rotary engine reach back to 1902 and the birth of the design’s creator, Felix Wankel. The German reportedly came up with the idea for this engine when he was 17, though it wasn’t until working with the Nazi party’s Aeronautical Research Establishment during WWII, and later with Germany’s NSU Motorenwerk AG in the 1950s, that his design took shape in a running prototype. NSU announced the Wankel engine to the world in the late ’50s, and in the ensuing years many companies signed agreements to license the technology. One of those, in 1970, was Suzuki.

At the time, Suzuki was strictly a two-stroke player in motorcycles. Sales in the exploding US market were good, but Suzuki knew that to continue to be a serious player throughout the ’70s and beyond it had to eventually expand into other engine designs—especially with Honda’s quiet and reliable four-strokes dominating and early emissions rumblings from the EPA beginning to be heard. Four-strokes were the obvious path, but others were already doing them well, and to Suzuki brass, the rotary design could be an option. Might this engine set Suzuki apart from Honda and everyone else? It might, management thought, and engineers were put to the task.

By ’73, Suzuki had its single-rotor engine up and running and a handful of minor patents and new technologies to go with it. Displacing 497cc, the new powerplant was both liquid- and oil-cooled, as rotary engines typically run quite hot. Another obstacle was high wear on (and the actual production of) the rotor housing’s inner surface. By using and advancing surface-treatment technology developed by Platecraft of America, Inc., Suzuki cleared this hurdle but had to build its own production facility to do so. New-think tech also extended to the two-stage carburetor, the vented, dual-pipe/twin-shell exhaust system (to cool the superheated exhaust gases), and the use of what Suzuki called a Peripheral Port design, which used three ports—one large and two small—with a butterfly valve to make maximum power and still preserve low-rpm throttle response and rideability.

RE-5 styling would be traditional and conservative. Or, mostly so. The twist would be a futuristic instrument cluster and taillight done by noted stylist Giorgetto Giugiaro, both of which were cylindrical in shape, apparently to remind everyone of the bike’s round ’n’ rotational heart.

Two other things were happening during '72 and '73 as Suzuki readied its RE-5 prototype for testing and, later, its debut at the Tokyo Motor Show. And each would have a profound effect on Suzuki's rotary fortunes. The first was the Arab Oil Embargo of November '73, which basically doubled the price of crude oil and caused massive shortages. The other, and more significant, fact was that Suzuki was not alone in developing rotary engines for motorcycles. Honda and Kawasaki had already built prototypes by that point, but it was Yamaha that shocked the world—and especially Suzuki—at the Tokyo show in late '72. There, it showed a twin-rotor rotary called the RZ201. Much has been written about this 660cc RZ being only a balsa-wood design exercise, a way to showcase possible new technologies and products. But the truth is that Yamaha came very close to putting the RZ into production.

“We’d actually begun to build production tooling,” says longtime Yamaha product-planning guru Ed Burke. “And I even got to ride one of the prototypes. It was very fast and really smooth.”

But Yamaha backed off despite the RZ201’s smoothness and power production. Not only did Yamaha see the bike primarily as a “statement machine,” in Burke’s words, “a bike that would say a lot about Yamaha technology,” but maybe not sell that many units, but they also saw the obstacles in its way. “We saw the oil and gasoline situation,” Burke says, “and we also knew rotary engines had poor emissions and below-average mileage. But also, rotary engines were ugly. In cars no one cared because you can’t see the engine. But a motorcycle engine is part of the aesthetic, and it’s very difficult to make a rotary not look like pump or compressor engine.”

Of course, Suzuki didn’t know Yamaha’s (or Honda’s or Kawasaki’s) plans or outlook, so it pushed ahead and very likely with some added competitive urgency. This added pressure may have been just the thing to either blind the company to the various obstacles or make it believe it could overcome them.

“I really do think Yamaha’s actions, and the overall buzz surrounding rotary engines at that time, led Suzuki to push forward with maybe a little more excitement and urgency than was prudent,” says RE-5 and rotary-engine guru Jess Stockwell. “[Suzuki] certainly went all out on the project.”

That it did. Not only did Suzuki come up with new technologies for the RE-5 and build a new production facility to produce the bike, but it spent millions more on testing, technical training, early promotions, press introductions, dealer trips, touring accessories, multi-page brochures and advertising, and much more during the bike's introduction and rollout in late '74 and early '75. It's fair to say Suzuki spent more designing, building, and promoting the RE-5 than any machine in its history (until the GSX-R750 came around a decade later).

“It is with great pleasure and pride that I announce on behalf of the Suzuki Motor Co. Ltd. the development of the RE-5 rotary-engined motorcycle,” wrote Suzuki boss Jitsujiro Suzuki in a beautifully done, multi-page color brochure that appeared when the bike debuted. “We believe this achievement marks the beginning of a new age in [motorcycling] history.”

Two bits of irony are interesting to analyze at this juncture. One was the appearance of Honda's GL1000 at the very same time (late '74), which in many ways was nearly as radical a departure for Honda as the rotary was for Suzuki. We know how the GL turned out for Honda. The other was the development of the GS750, in late-prototype stage by early 1975 and less than a year from production. Suzuki's fortunes and permanency in the US and the world would turn on that big, fine-handling inline-four GS of '76, so it's fascinating to wonder about the dichotomy of thinking that must have gone on inside Suzuki while the RE-5 and GS were being drawn, prototyped and tested, and just a year apart.

Generally speaking, customers and magazine editors greeted the RE-5 lukewarmly. There were fans in both camps, and road tests pointed out the bike’s strengths—engine smoothness, reasonable handling and comfort, and decent horsepower from the 500cc engine. But detractors soon outweighed the fans, complaining of excess engine heat, excessive throttle play, oil and fork seal leaks, an average seat, a tiller-esque bar with too much pullback unless the bike had a fairing, and funky styling. And so, despite the lush rollout, the explanations of features and benefits, the advertisements, and the colorful brochures handed out at dealerships and bike shows, the RE-5, despite all its new technology and uniqueness, simply never generated much excitement or retail sales over its two-year production span. Dealers had new bikes on the floor well into the late ’70s.

It’s true the RE-5 was a bit overpriced, slightly porky, a little underpowered, and thirstier than your average four, but it was much more than numbers that killed the RE-5. There were also the factors of complexity, mystery, and aesthetics, all of which joined forces with the lackluster numbers to drive the bike to an early death—and create a major sales disaster for Suzuki.

“All classic bikes have engines that are emotive or beautiful in some way,” says Yamaha man Burke, “but the RE-5, as well engineered and dynamically competent as it was, clearly had an uninspiring-looking engine. Not Suzuki’s fault; all rotaries are ugly, I think. But aesthetics do matter.”

Comedian Jay Leno, a collector extraordinaire and owner of a low-mile, first-gen Firemist Orange RE-5 much like the one we photographed and rode for this story, agrees the bike is funky, complex, and probably a mechanical mystery to most riders of the day. But he loves his anyway. "I'm a sucker for ahead-of-their-time failures," he told me. "They have character. The RE-5 is a good motorcycle; it's smooth, with a nice pull of power. It's relaxing to ride. It handles well even though the ergonomics are sorta strange. But, hey, it's a time capsule! People see it and don't know what to think. I tell them and they ask, 'What's a Wankel?' It's fun to ride a piece of history. If Suzuki had kept with it, they might have been successful. Hey, remember, the first wristwatches were called 'ladies bracelets with a clock attached' by men, but look how they turned out!"

Leno makes a good point, but even big-time fans of the RE-5 like Jess Stockwell, who owns more than 100 of the things, agrees that the bike was probably doomed due to the many obstacles stacked against it at the time. "The timing was just bad," he says, "and the bike's styling and outward complexity, and the reputation the rotary engine had at the time among the general public… None of that helped.

“Still, it’s a good motorcycle,” Stockwell says. “Keep ’em in fresh oil and they’ll run 150,000 to 200,000 miles without problem. Yeah, the carburetor is tricky to get right, and without clean oil, and plenty of it, the apex seals [which seal the rotor against the housing] can wear out. Overheating is a death knell too. But maintained properly, they’re bulletproof, and I love them. My 55,000-mile unit runs and looks new.”

Of course, the RE-5 story isn’t all negative. It left the world with a uniquely interesting motorcycle, one that a few thousand hard-core enthusiasts—like Stockwell, and Leno, and Todd Haifley—still love to ride, talk about, and show to the world as often as they can.

It’s also quite plausible that Suzuki’s big gamble and failure with the RE-5 was a blessing in disguise. If Suzuki had stayed with the concept and built a whole line of rotaries (as was its stated plan prior to ’76) and not built the GS750 and GS1000, the company would have surely disappeared.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/D6XTBEXPBOLPVQMIMNIF2DWDR4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QCZEPHQAMRHZPLHTDJBIJVWL3M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HXOUJXQWA5HBHGRO3EMJIGFMVI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3TIWWRV4JBBOLDVGRYECVVTA7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KIX5O23D5NAIBGFXBN3327DKZU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)