To be honest, I didn't really want to race in Europe. As far as I was concerned we had some unfinished business here in America. I wanted to beat Harley-Davidson and win the AMA championship a third time. I was committed to doing that. But Yamaha decided to pull out of dirttrack racing. I remember the meeting where this was announced; I was devastated. I could have cried, really. Yamaha offered alternatives, but I got up and left the room.

I had come to another one of those places in racing where I had to do something I wasn't interested in. But if I was going to move forward with my life as a professional racer, I had to get interested in going to Europe and competing in international racing.

I'd been to Europe before, of course: the Imola 200 in 1974, by invitation to compete against Giacomo Agostini; the 250 race at the Dutch Grand Prix at Assen that same year; and then there were the Transatlantic Match Races. The first one of those was especially memorable. I was trying to learn how to deal with the Europeans, and they were trying to deal with me. We showed up at Brands Hatch all set to race. Or so we thought. An old ACU track official--I swear, he must have been 90--apparently hadn't ever seen slicks before and announced I wasn't racing with them. I tried to explain it really wasn't part of his deal, that I had sponsorship from Goodyear and these were the tires that were going to be on my bike. Things heated up. The promoter showed up and told the ACU guy I was there to race and he didn't care what tires I used. The old duffer had to get one last dig in: "If it starts to rain," he said, "I'll black-flag your arse!" "If it f***in' starts to rain," I fired back, "I'm pulling off!"

There was Kel Carruthers, again, dragging me away, explaining how it would be good if I didn't start an international incident at every race we went to.

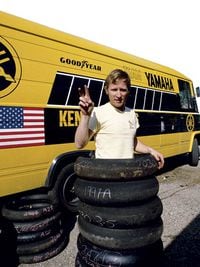

As I've said before, Kel was a big help in more ways than one. He started putting together our European program, which meant coming up with a budget. It looked like we needed $300,000--big money in those days. U.S. Yamaha was willing to provide equipment--very nice of them--but Kel would have to find whatever other money we needed. From my side, I contacted Leo Mehl, who was in charge of Goodyear Tire & Rubber's racing division. I also spoke with the Goodyear distributor at Daytona, Bill Robinson, who appreciated my loyalty to the company and the fact that I'd helped it develop its roadrace tires. An answer came back from Goodyear: They would help me go to Europe to race the GPs. Goodyear would provide tires and technical support. This was great! But I told Robinson I needed plenty of dollars, too-- 150,000 of them.

It started to dawn on me that maybe I wasn't exactly a factory rider, struggling as we were to put together our own program to compete in Europe. I wasn't that smart in those days. I'm not sure I'm any smarter now--I'm still struggling to find tires and money! In any case, Goodyear made the commitment and off we went. Kel and I had a small Mercedes transporter and two mechanics, Nobby Clark and Trevor Tilbury.

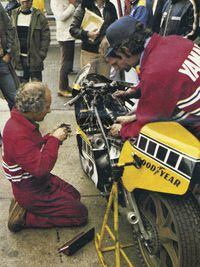

When we got to our first race it became crystal clear that, for sure, I wasn't a Yamaha factory rider. Venezuelan rider Johnny Cecotto was. It wasn't hard to tell; all we had to do was look at his equipment and then look at ours. We did have a Yamaha engineer by the name of Mikawa, and at some races we also had a Goodyear technician. But it was us against the factory, really.

So '78 was a piece of work. I was riding 250 and 500 Grand Prix and Formula 750 as well. We had just one bike per class; no back-up bikes. At practically every race it was my first look at the track. Usually, all I had was 30 minutes to figure it out. And not just the track, everything--the right lines, bike setup and tire selection, if there was any. There I was, aiming to beat reigning World Champion Barry Sheene, who'd usually seen the track a dozen times before.

And we were on Goodyear tires. We were on our own there, too, because nearly everyone else was on Michelins. I swear, some things never change! To say the Goodyear guys had their hands full is to understate the problems we faced. Usually, the Goodyear guys would show up at a track they'd never seen before, which meant they didn't have the right tires. That's a nightmare you really don't want to deal with. But deal with it we did.

But as it happened so many times in my career, someone took note of my situation and stepped forward to help. This time it was a gentleman named Bernard Cahier, a Frenchman who spoke perfect English. Cahier could see I was struggling at the Paul Ricard circuit, and asked about our tires. I told him the situation wasn't good, that the only thing we had that might possibly work here were the Goodyear tires we had for Daytona. Cahier may have been a photojournalist who knew mostly about Formula 1 tires at the time, but he knew--as I did--that this wasn't going to work, at least not very well. "But these tires will be very hard! Where's the engineer?'' Cahier asked me. "We don't have an engineer here," I told him. "I know the tires are too hard, but they're all we've got."

Cahier told me he knew Chuck Pilliod, president of Goodyear in America, and called him at home. It was probably the middle of the night, but Cahier wanted answers. "What's going on here?" he asked Pilliod. "This young man has ridden a magnificent race. But the tires--the tires are very bad. Why is there no engineer?"

At the very next race in Madrid, Spain, Goodyear technician John Smith was with us. Smitty, as we called him, was pretty excited. "Man!" he said. "I don't know what you said to the guys back in the States, but you should see all the stuff we've got!"

Smitty was right. Roadracing tire development was finally underway at Goodyear, and in a big way. There were major improvements in the compounds, and we had a choice of constructions, too. So we started to win races. In fact, we won enough races in the 500 class that I won the '78 500cc world championship and became the first rider ever to win a world championship in his first season of GP racing! Without Cahier, Mehl, Robinson, Pilliod and others at Goodyear, I'd have never won that title. If Goodyear hadn't put up the $150,000, I wouldn't have gone to Europe in '78. And who knows, if I hadn't gone to Europe that year, I probably wouldn't have gone at all. Remember, American riders were not exactly hot property in those days.

I think I helped change that.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OPVQ7R4EFNCLRDPSQT4FBZCS2A.jpg)