Adventure bikes—ADVs for short—are hugely popular right now. The basis for the machines’ appeal is this: ADV bikes are powerful, comfortable, feature-laden touring rigs that can potentially go off road. Most owners never feel the need to exercise their bike’s abilities in the dirt, but there are a few who do. And for those brave souls, we have these four up-spec, off-road-intended models: BMW’s R1200GS Adventure, KTM’s 1190 Adventure R, Triumph’s Tiger Explorer XC, and Yamaha’s Super Ténéré ES.

All of these machines share stable space with street-biased base-model alternatives and appear here with abuse-tolerant spoke wheels, long-travel suspension, crashbars, and other farkles aimed at satisfying the needs of off-road types. The BMW and KTM come set up from the factory for serious off-road work, while the Triumph is an example of how a standard Explorer can be modified using readily available Triumph accessories. The Ténéré ES we’ve included because it’s updated for 2014, and the previous model proved proficient in the dirt.

Since these bikes present themselves as off-road ready—some meekly, others assertively—we restricted their testing almost exclusively to dirt. The only pavement we pounded was that which led up into the San Bernardino Mountains and took us to the labyrinth of trails above Lake Arrowhead, California. In preparation for this adventure we outfitted the bikes with proper hiking boots in the form of Continental’s excellent TKC 80 knobbies (a no-cost option on the GS-A).

Through rain, sleet, and sunshine we rode, slid, and otherwise hammered these machines in search of their mechanical and performance limits. After returning to the office and sifting through pages of notes, this is what we found:

In standard trim Triumph’s biggest Tiger appears plenty burly, and Triumph says some 44 percent of Explorer owners take their bikes beyond the pavement’s edge. Since there’s so much interest in riding its products into the wild, Triumph whipped up the XC by adding a few choice items from its accessory catalog. To prep it for the jungle, the Tiger Explorer XC rolls on tubeless spoke wheels and also gets nylon hand guards, halogen driving lights, an aluminum bash plate, and tubular-steel engine guards.

The XC is a big bike, but compared to the enormous BMW Adventure, the Triumph almost seems slim. The seat is wide and soft, and once it’s in the high position there’s plenty of legroom. The broad tank, hand guards, and large, adjustable windscreen did a good job cutting through the cold on our way up to Lake Arrowhead, but sadly the Tiger was the only bike here not fitted with heated grips (they’re an option). Ride-by-wire throttle means cruise control and three-level traction control, but no engine modes or ABS modes beyond on and off.

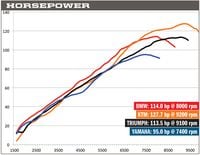

As an on-road tourer the Triumph is a graceful and enjoyable machine. Steering effort is moderate and response is linear, even on knobbies. The 1,213cc inline-triple is smooth spinning and sweet sounding, and you can easily cover 200 miles between fill-ups, despite the smallest-in-class 5.3-gallon fuel tank. Power is respectable, with 113.5 hp at 9,100 rpm and a steady stream of torque that peaks at 73.3 pound-feet at 6,400 rpm. Brakes are from Nissin, and they offer good bite and ample power. If you kept the Triumph on roads, you’d be mostly happy with your purchase.

Off road, it’s something else entirely. The further we ventured away from the security of the pavement, the more XC felt out of its element. The Explorer ranks the heaviest at 609 pounds fully fueled and feels top heavy at low speeds. Then there’s the fact that the suspension is too soft for even moderately aggressive riding, and adjustments are limited to spring preload in the front and preload and rebound in the rear. Results? The fork frequently bottomed with a sickening metallic thud, leaving the front wheel as the only suspension remaining. We rode the XC more gently than the rest, but the front rim still managed to sustain a nasty dent, and several spokes worked themselves loose. Where the other three bikes seemed fairly ready to be ridden off road, the Triumph seemed to say, “Please slow down.”

That impression extends to the electronics. The XC’s street-oriented TC and ABS settings are too conservative for off-road work. Disabling them requires digging deep into the menu system, and the features reset every time the key is turned off. With TC off, the Triumph’s motor is snappy and strong throughout the rev range but not unruly. It’s too bad the chassis can’t keep up.

The Explorer XC certainly looks the part, but after a few miles in the dirt it becomes abundantly clear that bolting on some off-road-ready accessories does not substitute for extensive off-road development. And so it’s clear that while Triumph did a great job making the Explorer fulfill the “touring” side of the adventure-touring equation—it’s comfortable, smooth, and capable of putting lots of miles under its wheels effortlessly—this test was about how these big bikes do off road. In this demanding environment, the Explorer simply couldn’t compete.

For 2014, Yamaha’s Super Ténéré received a revised cylinder head, new pistons, and a tweaked exhaust design intended to increase power. There’s also a larger windshield, new handlebar, and cruise control, and as before the bike has ABS, TC, and two ride modes. The ES bike, which costs $1,100 more than the $15,090 base bike, gets electronically adjustable suspension and heated grips.

None of these features is directly aimed at making the Ténéré better off road—and Yamaha makes the fewest claims about its bike’s abilities in the dirt—but the Super T definitely holds its own when the pavement ends. On road, the bike’s handling and ride quality are great—plush and controlled, just what ADV buyers seem to want. If only the new windscreen had improved the bike’s aerodynamics. All of our testers complained of turbulence behind the new screen, regardless of which of the four heights was selected.

Let’s get one thing out of the way now: This is the only bike here that doesn’t allow you to turn the ABS off easily. To do so, you have to put the bike on the centerstand and run it in gear until the ECU gets confused and disables the system. That’s a glaring shortcoming for anyone hoping to take the Super Ten off road because firing the brake nanny is a requirement. With ABS on, the street-biased programming prevents the bike from stopping effectively on broken surfaces.

Handling is stable but sluggish, and steering lock is limited, so sliding the rear tire to initiate turns is a necessary strategy on the Ténéré. The 1,199cc parallel-twin engine, despite its 270-degree crank, has remarkably little character beyond a commendably broad, flat torque curve. It’s also the least powerful in this group, with 95 hp at 7,400 rpm and 72.5 pound-feet of torque at 5,900 rpm; that’s 18.5 hp down from the next closest bike on the charts. Good thing the heavy flywheel and slow-revving behavior help the Ténéré find traction on loose surfaces. It’s a tractor too. The Yamaha will lug and chug its way up technical inclines that have the other riders slipping their clutches.

The engine is low-slung—that’s part of the reason this 606-pound machine feels lighter and more balanced than the Triumph, despite similar wet weights—and that also means ground clearance is at a premium. We bashed the Ténéré’s belly against the ground a lot despite full-hard damping settings and lots of spring preload in the rear. Yamaha must have anticipated our abuse and fit our testbike with an accessory aluminum skid plate—standard is a little plastic chin guard. Eventually the Ténéré succumbed to the beating: Repeated hits pushed the skid plate backward, causing a mounting boss—part of the oil sump—to crack and weep oil. Pack your J-B Weld!

As with the Triumph and the KTM, the Yamaha’s safety features reset every time the key is turned off. That’s especially annoying on the Ténéré, since turning ABS off is such a chore. But maybe that’s the point. Yamaha clearly doesn’t want the ABS disabled, and with the system on, you’re forced to ride more slowly in the dirt.

Dial back your speed and pick your lines carefully, and the Ténéré will take you much farther off the beaten path than you’d expect given its size and weight. The Super T is exactly what Yamaha intended it to be: a relaxed touring model that works well enough off road to make it an acceptable adventure machine. But that still leaves two machines well up ahead on the trail.

There’s no questioning the globetrotting ability of BMW’s R1200GS. It’s the original ADV, with decades of development behind that blue-and-white roundel. The Adventure model puts even more emphasis on the bike’s gelände capabilities with a bigger 7.9-gallon fuel tank (up from 5.3 gallons), more suspension travel, engine crashbars, tubeless spoke wheels, hand guards, and even a heavier crank and steeper head angle. This isn’t a mild makeover; it’s a bones-deep transformation.

The GS-A looks foreboding—not like anything you’d ever want to ride in the dirt. But the moment you get the wheels moving, all you can think about is how incredibly balanced, nimble, and stable the bike is. There’s simply no reason a 597-pound motorcycle should feel this good sliding sideways, wheelying over whoops, or boosting a hilltop jump.

Steering is ultra-light, brakes are strong and precise, clutch action is light and smooth, and throttle response is perfect. Let’s say that again: BMW nailed it. The motor is the most dynamic here, with snappy yet linear power and an enthralling exhaust note. Power output is impressive too. The new water-cooled Boxer engine puts down 114 hp at 8,000 rpm and 83 pound-feet of torque at 6,400 rpm, 13.7 hp adrift of the best-in-class KTM.

This is not a bike that’s all engine, though. Ride quality is superb no matter the terrain. The fact that the GS-A can float down the freeway like a Cadillac and resist bottoming when ridden hard off road is a testament to the effectiveness of BMW’s Dynamic ESA, which automatically adjusts damping based on suspension movement and other parameters. If you’ve resisted the allure of D-ESA until now, don’t try riding a GS-A; this big bike’s range of strengths will make you a believer.

In terms of features and electronic rider aids, the GS-A has them all, and they’re well executed and easy to use. The Enduro Pro ride mode is an example of electronics done right. It combines throttle response, damping parameters, and ultra-lenient ABS and TC settings to offer a perfectly tailored ride package that lets you slide and spin tires like a pro. ABS and TC are both easily disabled (on the fly!) and remain off until you say otherwise, even if you turn off the key. Bravo, BMW.

In Enduro Pro you can lock the rear tire completely, while front ABS only activates once the tire pushes. The system promotes forceful brake application and results in more confidence and thus more aggressive and enjoyable riding. Enduro Pro also has very limited TC intervention, but we still opted to turn it off since the GS-A is so much fun to steer with the rear. Less aggressive riders will appreciate the slightly bigger safety net provided by the base Enduro mode, which still allows enough rear-wheel spin to help point the bike but retains rear-brake antilock.

The only real flaw in the GS-A’s handling is vague front-end feedback. The front feels fine until it doesn’t—it slides quickly and with little warning. You soon develop the habit of transitioning to the throttle as soon as you’ve initiated a turn, both to avoid pushing the front and because the GS-A is so much fun to power slide.

In slow technical situations, the Beemer’s chassis remains totally poised, but the engine is still prone to stalling, despite the added crankshaft weight—it’s 2 pounds heavier than on the base GS. That, along with the cloudy front-end feedback, are two of the three reasons that the GS Adventure isn’t our number-one pick for a dirt-biased ADV machine. The third reason is price. At $21,550, it’s the most expensive bike here by nearly $5,000. There’s no doubt the BMW comes packed with technology and inspires confidence, and for some riders there’s no ceiling on what that’s worth. But we can’t ignore that difference. Our internal debate is telling. We agreed that if the BMW were within a couple of grand of the KTM it would have taken this comparison. But it isn’t, and it didn’t.

KTM wowed the ADV world earlier this year with its 1190 Adventure, a clean-sheet construction with an 1,195cc RC8 R-derived engine and better street manners than just about any KTM before it. The Austrian firm was quick to point out that there would also be an R version of the Adventure, built expressly for those who translate the term “adventure” into “I want to really go off road.”

The R suffix means over an inch more suspension travel than the standard bike (now 8.7 inches front and rear), bright-orange crashbars, larger 21-inch front/18-inch rear wheels (up from 19/17), highly adjustable (but not electronic) suspension, a taller seat, and a shorter windscreen.

This bike looks like an oversize enduro because that’s exactly what it is. It’s tall and lithe and that narrow. On the road the Adventure’s suspension is borderline harsh, and there isn’t much in the way of wind protection. This is the only bike here without cruise control, but the Adventure does have heated grips, and while the seat doesn’t have a heating element, the rear header serves the same purpose. That doesn’t matter, though, when you’re standing on the pegs attacking the trail.

And that’s the thing. The Adventure R works so well off road that you don’t just traverse terrain, you attack it. That stiff suspension comes into its own in the dirt, where the KTM always feels like it can hit ridges and ruts harder and faster. The bike tips in at 530 pounds fully fueled, which is still beefy but 67 (!) pounds lighter than the larger-tanked BMW. Between its lower weight and consistent, predictable handling, the KTM proved much less tiring to throw around. Curious, considering it’s also the bike you ride the hardest.

KTM’s feisty V-twin cranks out the most power here: 127.7 hp at 9,200 rpm and 81.5 pound-feet of torque at 7,400 rpm. Reigning all that power in is a useful Off Road ride mode that caps power at 100 hp, softens throttle response, and increases TC threshold to allow the rear tire to spin twice as fast as the front. The Off Road ride mode doesn’t carry over to ABS, however, so you have to manually switch to Off Road ABS from the Road default via the straightforward menu system. Like BMW’s excellent Enduro Pro ABS parameters, KTM’s Off Road setup allows you to lock the rear tire and only butts in on front-brake application when the wheel locks. Overall, the electronics are quite good and suitably aggressive for a bike with this pedigree. As with the Yamaha and Triumph, ABS defaults to on after the key is turned off, but unlike KTM’s road-going 1290 Super Duke R, the systems don’t reset when the kill switch is flipped. There are Sport and Street ride modes for on-road use as well.

One area where the KTM clearly surpasses the competition is in front-end feel. The KTM steers slower than the BMW, but it also transmits more feedback from the front tire, folds over slower, and is easier to recover. And this is the only bike that wheelies on command, and that big 21-inch front wheel is noticeably better at rolling over rocks, roots, and other obstacles. Plus, the KTM’s wheels are sized right for serious off-road rubber.

This comparison has a heavier dirt bias than your average ADV test, and with that in mind the KTM comes out ahead. Not only is it the best dirt bike here—by quite a margin—it’s also the best value. At $16,799, it’s $4,751 less than the BMW. And for the amount of pavement you’ll ride connecting forest roads, the Adventure R is no worse than the GS-A as a streetbike. Its agility and spirit offsets its stiffer suspension and slightly vague front-end feel on pavement. The KTM spots the Beemer some sophistication and comfort but not $5,000 worth. If you truly intend to do the majority of your riding in the dirt, KTM’s 1190 Adventure R is the best adventure bike for you.

- ZACK COURTS

- ASSOCIATE EDITOR

- AGE: 30

- HEIGHT: 6'2"

- WEIGHT: 185 LB.

- INSEAM: 34 IN.

I’m pretty smitten with ADV bikes; I like the comfortable riding position and the high-tech gadgets, but I really love the ability to explore a dirt road if the whim strikes me. So, I’m not interested in the Yamaha or the Triumph. They’re both plush sport-tourers with rugged looks, but I want more than that. BMW’s R1200 GS-A, for example, delivers much, much more. The word that always comes to mind when I ride this bike is “magic.” I just cannot believe how well it works in any situation. Cruise down the highway? U-turn on a fire road? Equally easy on a GS and for no good reason; just look at the size of the thing!

However, if there is one bike for me in this category it would have to be KTM’s 1190 R. It’s much lighter and much cheaper than the Beemer and inspires more confidence on a dirt road than any bike this size ever has—GS included.

- BRADLEY ADAMS

- GUEST TESTER

- AGE: 25

- HEIGHT: 6'3"

- WEIGHT: 190 LB.

- INSEAM: 34 IN.

As a group, these are some of the most versatile motorcycles currently in production. Triumph’s Explorer XC gives Yamaha’s Super Ténéré ES a run for its money in most ways, but that soft fork just doesn’t cut it. I love the Triumph’s smooth three-cylinder engine, but the ES as a whole is more user friendly, with better (and elecronically adjustable) suspension. If only the motor had more pep.

Further up the rankings are the 1190 Adventure R and R1200GS Adventure, the latter of which surprised me with its outstanding suspension package and unreal off-road handling. How can a 600-pound motorcycle work this well? It’s amazing. I can see how the KTM’s performance could sway serious off-road riders to the orange side, but I thought the bike’s suspension was too stiff, and resetting the electronics was a pain.

- Marc Cook

- Editor in Chief

- AGE: 50

- Height: 5'9"

- Weight: 185 lb.

- Inseam: 32 in.

Oh, man. Is this a tough one. Were I asked to pick one of these four for myself, it would set off hours, days, or weeks of agonizing self-appraisal. What do I value more, authentic off-road ability or on-road comfort? How much touring/commuting plushness am I willing to give up to gain capability off road? I’m sure you’ll have the same questions.

Despite the throat-tightening cost, I have serious affection for the GS. It totally looks the part while also handling off-road duties better than it has any right to.

But I’m a sucker for character, which the KTM has in abundance. It’s at this point I get to pull a fast one—admit the machine I most want isn’t one of these four, it’s the KTM’s “little” brother, the standard 1190 Adventure. It comes with the same fantastic engine, awesome brakes, cutting-edge electronics, and visual swagger. But with a lower seat and better front-end feel on the street. Perfect!

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)