Night and day. That was my thought after just one lap aboard Honda's all-new 1986 VFR750F, which happened at the bike's sneak-peek launch at Willow Springs Raceway in February 1986. I hadn't been part of the Motorcyclist staff in '83 when the V45 Interceptor debuted, but I rode one while in college and then others during my first months as a staffer in early '85. I wasn't caught up in the hype that surrounded the first Interceptor's launch, but after just that one lap at Willow, I knew immediately that Big Red's next-generation V-4 was an entirely different animal.

It was throbbier and more mechanically musical than the V45 thanks to the 180-degree firing order and exotic, gear-driven cams. More comfortable, too, due to plush suspension and better ergos. It was also significantly more powerful thanks to intake, cylinder head, and exhaust enhancements, lighter due to the liberal use of aluminum, and better handling thanks to optimized chassis geometry, better engine placement, and suspension quality. Finally, the VFR was beautiful, with amazing detailing, fit and finish, glossy paint, and beautiful alloy bits—some cast, some machined.

These attributes you could see. The big unknown was reliability. The first-generation V-4s powering the Magnas, Sabres, and Interceptors starting in 1982 had camshaft-wear problems and other issues that didn't align with Honda's reputation for quality and durability. Many wondered if the VFR's engine would be similarly afflicted. The bike's—and the brand's—reputation was on the line.

One way to regain a reputation is to prove it. And that's how fellow Motorcyclist staffer Nick Ienatsch and I found ourselves in Laredo, Texas, at Uniroyal's circular, 5-mile asphalt test track along with a bunch of racers and industry types—and four brand-new VFRs. This was where Cycle World had set the outright 24-hour average record of 128.3 mph in 1985 with a first-generation Suzuki GSX-R750. This was the record Honda wanted, needed to beat.

Honda’s Tom Hicks, part of the product evaluation team, knew that besting the record would speak volumes about the VFR’s durability and performance—it had worked for Kawasaki, twice, once in 1973 with the Z1 and again in 1977 with a KZ650, both records set at Daytona. But it was especially important in this instance given the problems that had plagued Honda’s earlier V-4s. And it would be a fine retort to the noise the GSX-R was making in the enthusiast marketplace. “The GSX-R750 was the gold standard at the time,” Hicks told me. “What better way to introduce your exciting new motorcycle to the press and public than to break a speed and endurance record your competitor’s bike had just set?” And it wasn’t just the GSX-R. By 1984, the supersport market was growing rapidly. Kawasaki had launched the Ninja 900, Yamaha touted the brutish FJ1100 and, later, the five-valve FZ750, and Suzuki had a broad line of sporting GS models eventually capped by the GSX-R. Honda needed something big to be heard above the clamor.

The world-record plan was obviously risky. Engine problems or a badly injured rider could derail the effort, and the resulting black eye could end up being too much for a new bike to overcome. But Hicks was confident in the bike and invited all the major magazines to take part so the coverage would be as broad as possible. Cycle and Cycle World passed. Not wanting to contribute to the beating of its own hard-won record, CW would instead ride one of the record bikes home to California as part of its story.

In the end, seven racers and journalists—myself, Ienatsch, John Ulrich from Cycle News, Dain Gingerelli from Cycle Guide, Rick Mitchell from Motorcycle Industry magazine, Rider's Brent Ross, and 250GP racer Christine Baur—made the trip to Laredo, along with a host of Honda, Metzeler, AMA, and FIM staff, some 50 people in all. Other Honda riders included product-planning specialist and ex-Superbike pilot Mike Spencer, race-team mechanic Phil McDonald, product evaluation manager Dirk Vandenberg, and R&D test rider Kiyoshi Aizawa.

Honda brought two 750s and two tariff-beating 700s. The plan was to run one 700 and one 750, using the extra bikes for spares as needed. They were bone-stock engine-wise, though they did get slightly wider wheels to allow the use of hard-compound Metzeler endurance slicks, the only tires that could stand the heat and abuse of 160-mph speeds on hot asphalt for extended periods and not come apart; every street tire Honda tested at Laredo chunked badly due to the high speeds and the bike's weight. For faster pit stops, the fuel tanks got a Daytona-spec dry-break for quicker fills, and the wheels got captured spacers for faster changes. Otherwise, these were stock-spec Hondas, albeit ones prepared very carefully.

When Nick and I got our first look at the bikes the morning following our arrival, I remember having reservations over what we were about to do. This was a huge, and hugely expensive, effort. That, and the consequences of failure, had me thinking this would not be the ride in the park I’d imagined. There were the dangers of tire failures at speed, of course. But what really freaked me out were the coyotes, pigs, badgers, and rabbits that populated southern Texas. Hicks told us of several incidents during night testing when riders hit rabbits or saw wild pigs wandering trackside. If even larger animals were part of the mix, well, things could get ugly.

I remember thinking the riding was going to be easy, right until my first 36-minute, 18-lap stint an hour or two after the two bikes—one 750 and one 700—were flagged off at about 1:30 p.m. on April 26. Mentally, it was the pressure of screwing up, of ruining things for everyone. The physical part was, well, physical. I’m a big guy, and even back then I was 195 pounds, so staying “under the paint” for nearly 40 minutes at a stretch was painful. Keeping an eye on the tach, the track, and any wandering animals meant rotating my head as far back as I could while lying on the tank, and within 10 minutes my neck began to ache. This was not like a typical endurance race where I could move around. I was basically stuck in one position, and moving my butt, arms, and head even a little caused turbulence and slower speeds, which the pit board that whizzed by every two minutes confirmed. Not wanting to let the troops down, I stayed put and dealt with the discomfort.

A few hours into its run, the VFR750 Rick Mitchell was riding blew up. “It suddenly lost power,” remembers Mitchell. “I coasted to a stop and waited for help. Dirk Vandenberg arrived on an ATV, and I told him what happened. Not believing me, he jumped aboard and hit the starter button. Ugly noises.” After Vandenberg and race-team manager Udo Gietl determined the bike was terminal, the backup VFR750 was pressed into service, starting a fresh 24-hour run in the late afternoon, albeit at slightly slower speeds so as not to overstress rear tires, which had been chunking on the 750 during the hotter part of the day. The tire problem was expected from testing; the blown engine was a shocker. Was Honda’s all-new V-4 somehow flawed, as early VF750 engines had been? Had the factory modified the engine for extra speed and gone too far? In the pits, theories—conspiratorial and otherwise—circulated quietly.

The two bikes continued throughout the afternoon and into the evening. Riders swapped every 36 minutes or so, while the FIM’s Jack Dolan kept an eye on the lap-counting. The techs listened for problems as the bikes ripped by and checked them over when each bike finally came to rest for either a 10-second fuel-fill/rider change or a 30-second full-service stop that included a new rear tire.

At night, the game changed completely. Daylight was my security blanket. But at night, with the headlight boring maybe a 50-yard hole in the blackness and with no way at those speeds to react to anything that might suddenly appear in that eerie, illuminated cone, that blanket disappeared. My nighttime stints were surreal, and the images of ripping around the circular track in complete darkness remain crisp to this day. It was just me, the cone of light ahead, the warm orange glow of the VFR’s instruments, and the satisfying throb of the V-4 at redline, the optimistic speedometer needle sitting around 165 or 170 mph. Every couple of minutes, with the track’s painted lines blurring by in my lower peripheral vision, a glow of light appeared to my left. The glow increased in size, and seconds later I ripped by the massively illuminated pits, my eyes straining to read the well-lit pit board being held by a crew member standing just a few feet off my specified lane. A second later everything went dark, my eyes readjusted, and I did it all again.

Gingerelli got an early morning wake-up call that highlighted the hazards of riding flat-out at night. “The headlight fuse blew while I was in the saddle at about 2 a.m.,” he remembers. “Sudden darkness while doing 160 miles per hour has a way of perking you up.” A while later Honda’s Mike Spencer had his own special moment aboard the 700. “I hit a badger, a big one,” Spencer said once back in the pits. “I had no time to react, and the impact blew the front end into the air. I slammed my face into the triple clamp, loosening my front teeth, but somehow didn’t crash.” Vandenberg rode to the impact point on an ATV, found the badger’s remains, and brought them back to the pits to the amusement of everyone—except maybe Spencer.

Early morning turned to noon, and soon it was time for the 700—right on schedule to beat the existing 128-mph average speed record—to finish its 24-hour run. Hicks was chosen to ride the final stint on the 700, and the crew messed with him by hiding behind the transporter when he rolled into the pits after crossing the finish line. Empty pit? No celebration? Gotcha. Hicks was soon drenched in champagne. The 700’s 24-hour average was 138.907 mph.

Several hours later it was the 750’s turn to finish, and the crew geared up for another celebration. Racer and stuntwoman Christine Baur was tagged to ride the final stint on the 750, and boyfriend Phil McDonald got the idea to give her a special visual treat as she crossed the finish line on the next-to-last lap—a mooning by eight or 10 of the male crew, all lined up on the steepest part of the banking. (Please note that your humble correspondent did not take part, except to photograph the scene.) More champagne flowed when Baur slowed to a stop a couple of minutes later as the riders and crew celebrated setting a new record during one of the longest and most amazing 24-hour periods in their lives—and realized they could finally get some sleep.

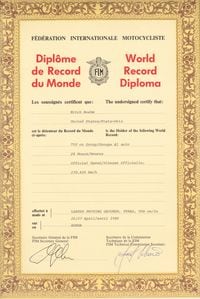

In all, we’d set five new world records on the VFR750: 100 km (146.63 mph); 1,000 km (144.3 mph); six hours (143.9 mph); 12 hours (144.1 mph); and 24 hours (143.108 mph and 3,436 miles).

These records helped Honda prove not just the VFR’s speed but its durability too. But what of the broken 750? A flawed piston casting was found to be the cause of its demise, which Honda R&D diagnosed using scanning electron microscope. (Photos and analysis have been published, proving the claim.) That’s a freak occurrence and a shame, as Honda pistons have earned a reputation for extreme durability over the last five or six decades. Of course, the second 750 ran like a charm, as did the 700.

In fact, when Cycle World examined the 750 engine's internals a month later after riding the bike back to California, it found the engine not only bone-stock but barely worn. "After measuring piston and ring wear, bearing clearances and valve lash," CW wrote, "we concluded that the wear the engine sustained was minimal. Honda has not only demonstrated that the VFR750 is one fast motorcycle, but that it's one tough motorcycle."

An interesting irony here is the fact that the VFR, during development, did exhibit some cam-drive fragility as the new, higher-revving V-4 was being tested. “Several times early on,” VFR Large Project Leader Isao Yamanaka told me recently, “we experienced cam-drive breakage due to the resonance resulting from the higher revs.” That’s amazing considering that the VFR’s gear-driven cam design came from endurance roadracing. But obviously, R&D figured out the cause and remedied it.

“As punishing as that effort was on machinery,” Mike Spencer says, “I’m not surprised the two bikes did it so easily. Throughout development, the VFR was just really, really competent. Every test I took part in, in Japan, Europe, and in the US, the thing just got better and better. The engineers worked their butts off on that motorcycle, engine and chassis, making sure it was fast, handled well, and was bulletproof. And except for that one bad piston, it was!”

I sensed all this at Willow Springs that crisp February afternoon, that the bike was “night and day” better than the VF750 so revolutionary (if fragile) in its day. And after a grueling three-day “vacation” in Laredo, Texas, Nick and I had helped conclusively prove the point.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2TGQFL4MJCK246SSSWNSADTSEA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OPVQ7R4EFNCLRDPSQT4FBZCS2A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YBPFZBTAS5FJJBKOWC57QGEFDM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/W5DVCJVUQVHZTN2DNYLI2UYW5U.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/C3VIRIAYNZCTJAZNRLREDS3JCM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XXWKUKITWRAF3HCJAWGJ25V7BA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MALB2TULBRCQJJ3P3UXMU2N7QE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6KMLYR3T5GMNA7F7URZVLO72I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RIBH2PB5DBFEZFEYXDOD5Z6ECA.JPG)