President Thomas Jefferson was a man who kept incredible, detailed records, and some have speculated that this almost compulsive need to tally fueled his curiosity. While his predecessor, John Adams, had a true worldview, worrying about the French Revolution, Jefferson's sights were closer to home: He wanted to know everything about the new American West, a vast territory extending from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean. By the early 1800s, westward expansion had become a hot topic for the president, and he secretly ordered Meriwether Lewis to lead an expedition to the area. Jefferson's motives were clear: "To explore the Missouri River and such principal streams of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean...may offer the most direct and practical water communication across the continent, for the purposes of commerce." Lewis and William Clark used a $2500 expansion stipend to assemble a team of 33. The expedition commenced on May 14, 1804 and ended on September 23, 1806 when Lewis, Clark and the aptly named Corps of Discovery returned to the heartland, leaving behind an 8000-mile trail of hardship and sacrifice and bringing home unfathomably hard-won knowledge.

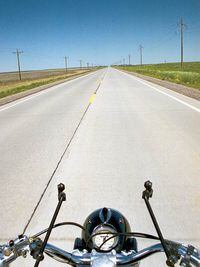

Dial your time machine ahead approximately 198 years and you'll find Dennis Wolter and a corps of hardy motorcycle riders attempting to follow the Lewis and Clark trail from east to west. Oh, and get this: They made the trip on two-stroke 250cc Puch "Allstate" motorcycles once sold at your friendly neighborhood Sears. Not something, in other words, you'd see in a Ken Burns documentary.

"But...why?" you ask. Wolter sums it up: "I've always been a history buff and have been fascinated by the Lewis and Clark expedition. I wanted to see what was left of the trail, and I wanted to do it on the Allstates." Wolter pauses, preempting the next question with, "Because I wanted to prove you could. Anyone can do a trip staring through the windscreen of a new Harley. Much of the trip was on logging roads, and sometimes we had to lift the bikes over fallen logs. You can't do that with a 500- or 600-pound motorcycle." Along the way, Wolter turned his band of riders into Allstate believers, to say nothing of the scores of motorcyclists he met along the way. Although certainly not as dangerous or austere as the Lewis and Clark expedition, Wolter's ride had two ground rules: The riders would stay at campsites whenever possible and live simply.

Wolter describes this journey as the trip of a lifetime--an opportunity to see the still vast American West at a pace gentler than that offered by the great interstates.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)