Power cruisers inhabit a strange corner of our moto landscape, putting aside traditional forms—meaning they don't have to look like Harleys to be accepted—and they even break from expected configurations to arrive at what each manufacturer thinks is the ultimate design. Put it this way: There isn't even an air-cooled, pushrod V-twin in this test. That's how you get bikes as diverse as the Ducati Diavel Carbon, the Honda Gold Wing Valkyrie, and the Star VMAX in a single comparison. A trio powered by a high-tech, relatively small V-twin, a smooth, touring-derived flat six, and a rollicking, big-inch V-4.

All these compelling machines represent the corporate philosophies of their makers—the Honda is smooth and seamless, the Ducati rowdy and high-tech, and the Star is overtly powerful. The last of which makes sense considering Yamaha—before there was a Star Motorcycles—built the V-Max (as it was then called) to not just escalate but end for all time the performance-cruiser wars. That the Max lasted from 1984 to 2007 says a lot, doesn’t it?

Today’s landscape is dominated by these three bikes, though you should also keep in mind Harley’s V-Rod (they’re still making that, huh?), Suzuki’s M109R, and the outlandishly large Triumph Rocket III. Bringing the Ducati, the Honda, and the Star together would help us understand where the two newest players fit. After all, Ducati gave the Diavel a number of important updates for 2015—including a power boost to 162 hp claimed—while the Honda was all new last year. Like the original, the new Valk takes the Gold Wing touring platform and strips it to the bare essentials. Unlike the original, which wrapped the 1,500cc Gold Wing in super-size cruising attire, the modern Valkyrie covers the 1,800cc flat-six in flowing hot-rod-inspired finery. Would that be enough to unseat the performance-oriented VMAX or the stunningly capable Diavel? Read on.

Quick answer to that: No, not quite.

It's sometimes useful to use automotive analogies to sum up the feel of a motorcycle. In the case of the Honda Valkyrie, it's like high-performance luxury sedans from Mercedes and Cadillac. Plush, powerful, sleek. In contrast to the other two snarling beasts, the electric whine of the Gold Wing Valkyrie is far more sedate. It has a bit of a growl but just enough to let you know it's serious.

Unlike the other two powerplants, this one is not a racer; it’s a tourer, so power comes on from the moment you engage the clutch and doesn’t stop until you hit the rev limiter around 6,500 rpm. Power is extremely flat but universally present. Magazines use the phrase, “It doesn’t matter what gear you pick” frequently, but it’s never been more true than on the Valkyrie. And true to its heritage as a long-distance tourer, it’s so very smooth. The Valk lulls you into thinking you can just let it do all the work for you, the opposite of the very demanding (and rewarding) Diavel. No electronics between you and complete stupidity, though the very long and substantial bike is very forgiving. Mileage is a middling 40 mpg but is offset by a 6-gallon tank, which easily provides the longest range in this test.

The Valkyrie’s descent from a tourer wasn’t very far, and although the layout’s been altered from the Big Mama Gold Wing, it’s still upright and relaxed. The brief-looking seat is actually plush and supportive, unless you’re less than 150 pounds, in which case it’s a little too firm. The big side-mount radiators (one of a few characteristics the Wing shares with the Diavel) are claimed to drive heat away from the rider, but we were happy to cozy up to the big, warm machine in our late-fall test. The large LCD instrument panel is a step in the techy direction but looks primitive in comparison to the higher-definition screens of the Diavel. It’s positioned well for viewing in a full-face helmet.

Cruiser riders will prefer the Honda’s beefier grips over the 7/8-inch grips of the smaller bikes. It also has the lowest passenger pegs, which, in addition to adding comfort for potential passengers, also gives the rider another place to put his/her feet on a long ride. All the passenger accoutrements (seat, grab rails) are removable if you want to remake the Valk as a solo machine; but doing so kills what little storage space you have.

Interstate riding isn’t the best use for these bikes, but passing cars with the barest flick of the wrist is fun and satisfying. Predictably, the Gold Wing was master of this domain with a relaxed riding position, long range, and a carefree ride, letting its pilot relax into a long slog and watch the miles roll by. The stock suspension settings on the Valkyrie are the plushest; the wheels roll over nasty bumps without really disturbing the rider, yet the chassis maintains good pitch control. Honda’s done a great job refining this platform.

But sometimes being “nice” is the most backhanded of compliments. And that’s why the Honda is third of three in this comparison. While it’s definitely not slow, the fact remains that it trailed the mighty VMAX down our rough, slippery dragstrip by 1.33 seconds. And while it always feels willing and able to scorch the back tire, the Valky is just so smooth and composed that it rarely excites. Maybe that’s okay for you, and we’d understand completely choosing the Honda as your daily ride. The Honda is more refined and comfortable than the Ducati or Star by quite a sizable margin. But this is a category supposedly populated by rough-and-tumble machines. The Valkyrie is Clark Kent frantically looking for a phone booth.

If we had to give Star's VMAX a car metaphor, it would be something like a Dodge Viper—ridiculous, outlandish, totally in your face about its performance capabilities. A two-wheeled codpiece. As the VMAX has always been.

Unlike the ill-handling last-generation V-Max, this one backs up its insane motor with a proper chassis and brakes. But with almost 1,700cc of V-4 anger, it really doesn’t matter how good you, the chassis, the brakes, or anything else is. Grab a handful of throttle and things will get twisted. Although the VMAX’s ride-by-wire programming keeps it from being totally unruly, it doesn’t have anything like the programmable digital nanny on the Diavel. Meaning traction control is in your right fist. So the MAX will light up the tire in third if you shift in the right spot or are exiting a corner.

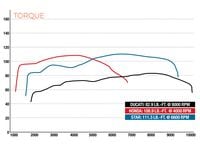

There’s almost no way to overstate the influence the VMAX’s engine has on the whole. Consider the 170.8 hp or the 111.3 pound-feet of torque. Consider that torque never dips below 90 pound-feet from 2,600 rpm until the rev limiter at 9,500 rpm. Consider, finally, that the next-strongest bike in this comparo trails the Star by an embarrassing 36.2 hp, and even the torque-rich (and larger-displacement) Honda trails the VMAX by 2.4 pound-feet at peak. That is a winner-takes-all approach to power, and Max’s brawny (but smooth) V-4 goes home with all the trophies.

Comfort on the VMAX isn’t bad, but it’s definitely not what it is on the other two. Given the nature of the bike, the seat’s most important function is keeping your ass in place, which (with its tall bump pad/gas cap cover) it does very well. It would take a backside broader than any we brought along on this voyage to fill Mr. Max’s perch. As it is, the wide seat and motorcycle cross section made the ground a faraway place. That said, the layout worked well for all of us. In between the overly engaging Diavel and the snoozy Valkyrie, though, the wide midsection had us all splaying our legs fairly far apart. The yellow digital display is fairly low and too close to really look at casually while riding, while a large white shift light protrudes from the large tach/speedo. Apparently its use/setup is one of those dark arts covered in the manual. We weren’t given one.

We had a bit of anxiety about testing the VMAX on very tight roads. With all of that power, things could go south in a hurry. So, of course, the first thing we did was point it at the twistiest road we know. The ABS-backed brakes are strong, and the suspension, while firm, is better than you’d expect on a 751-pound beast. And while the VMAX’s steering is relatively neutral and there’s as much cornering clearance as you’re likely to want, you never completely lose the notion that you should respect its heft and power. If there’s a drawback to be found on the VMAX, it’s that you really need to keep yourself from twisting the throttle too hard when in technical terrain. Heck, any time the bike is leaned over you could get wheelspin if you’re not feeding in thrust gradually.

It’s this very power-over-handling approach that has served the VMAX so well since 1984 and makes it a respect-worthy machine capable of waking your adrenal glands from a coma. And, perhaps, in a perfect world of speed-is-all capability, it would win this comparison. Instead, though, it’s more a case of 171 one-trick ponies.

Let's make one final automotive analogy for the Ducati Diavel Carbon, this time something supercar-casual like Ferrari's California or a Maserati of some sort. While the Valkyrie was making a comeback, the Diavel was getting a redo. Although it came out after the VMAX, it's already been updated after just two years. It seems no bike is exempt from Ducati's ultra-fast racebike development schedule. The remake brought a new full-LED headlight for a new frontal look and greater visibility, new scoops and radiators, a new seat, and a retuned dual-spark engine that now hits its torque peak even earlier.

The thing that makes the Diavel a cruiser (or at least cruise-capable) is the supremely advanced engine management. Even in its tamest mode it’s a raucous beast but one capable of taking it easy as well. It makes the brain-switching-off thing that many seem to appreciate with cruisers possible in even a sporty bike.

Despite having the smallest engine, the Diavel posts stout numbers: 134.6 hp at a relatively high 9,200 rpm (the VMAX peaks at 8,800 rpm and the Valkyrie at just 5,800) and 82.9 pound-feet of torque, the least in the test. While the Diavel’s output is impressive within the context of Ducati’s Testastretta 11° line, it doesn’t have that basement-full-of-torque feeling of the other two, which may or may not be an important part of your power-cruiser personality checklist.

Frankly, we don’t mind too much, mainly because the Diavel actually accelerates quickly. Its 10.83-second run is fairly poor form for the Diavel, an artifact of our dragstrip’s crummy surface more than anything else. But on the same day the other two ran, the Ducati aced the tire-spinning Star (by 0.34 second) and the under-powered Honda (by 1.67 seconds). Why? Low weight is one reason, as it’s 163 pounds lighter than the VMAX and a truly stunning 222 pounds less hefty than the Valkyrie. The other is traction. Even with the multi-adjustable traction-control turned off, the 240mm-wide rear tire hooks up and drives this devil forward.

Speaking of Ducati Traction Control, it’s an important part of the Diavel’s makeup. It lets you set not only how aggressively the bike will let you ride (how much wheelying and wheelspinning it will allow before intervening) but how quick the throttle response is. In Sport mode you get all the glory of its ponies in a fairly hair-trigger fashion. The Touring mode offers full power with a soft throttle response, while Urban limits the Diavel to “just” 100 hp and even tamer throttle response.

Ducati’s Diavel also fit all of our riders very well. Our smallest rider would have preferred less of a reach to the flat bar, but that was her only complaint. The seat, which was one of our sourest notes last time we tested the Diavel, was universally praised here. Before it was an overly firm, sportbike-inspired, forward-sloping piece, which has been replaced by a flatter, bucketed one that offers support while still allowing movement and weight shifting. By our reckoning, the Diavel takes the class because it has performance across the spectrum. It handles extremely well, has plenty of cornering clearance, super-stout and confidence-inspiring brakes, and suspension calibration that keeps the chassis under control. Always. Yes, it can be harsh over certain kinds of surfaces, especially the poorly laid concrete California calls freeways. And it doesn’t hew to the traditional low-long-easygoing cruiser form. We can live with that-—and make it our own little deal with the devil.

ZACK COURTS

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

AGE: 31

HEIGHT: 6'2"

WEIGHT: 185 lb.

INSEAM: 34 in.

Before this test, I thought these bikes would be too different for comparison. Truth is, they all fit the muscle-cruiser bill; it’s just a matter of what you want.

At the center of the whole genre is the VMAX, and its reputation is fully earned. There isn’t anything that matches the VMAX for pure, NASA-strength thrust. It’s epic and utterly addictive. The Valkyrie is an extremely refined bike but almost too much so; it’s fun to ride but too polite for this group.

For me, the Diavel is the third bowl of porridge. Yeah, it’s expensive, but the Ducati has the most amenities, the best power-to-weight ratio, and brutish looks that speak to my demonic side. Plus it’s 163 pounds lighter than the VMAX and with far more sporting prowess than the other two can actually carve a canyon pretty respectably. For a washed-up roadracer like me, it’s the perfect cruiser.

MARC COOK

EDITOR IN CHIEF

AGE: 51

HEIGHT: 5'9"

WEIGHT: 190 lb.

INSEAM: 32 in.

If you weren’t around when the original V-Max was introduced it’s hard to understand the current one. Outrageous? Yes. Crazy fast? Of course. A caricature of a caricature? Precisely!

Although I’m deeply impressed every time I ride a Diavel—it’s simply so much better as an all-around performer than any bike called a cruiser in the brochure has a right to be—I think it’s too viscerally aggressive for the class. I’m not talking power here; I mean its personality, which is insistent, nervous, over-caffeinated.

The Valkyrie, which I also admire for being incredibly smooth and refined, is at the other end of the spectrum, just a bit too reserved and tame for me. Which leaves the unruly VMAX, a machine that is still what its makers intended it to be all along: a snorting, high-power raised middle finger to the rest of cruiser-dom. My kind of bike.

ARI HENNING

ROAD TEST EDITOR

AGE: 30

HEIGHT: 5'10"

WEIGHT: 175 lb.

INSEAM: 33 in.

As a general rule, the more torque a bike has the easier it is to launch. That’s true—to a point. And it would appear that point rests somewhere around the 110 pound-feet mark. The VMAX has the most torque here but proved the hardest to get off the line due to the simple fact that the rear tire couldn’t handle the power.

The heavier Valkyrie had an easier time getting off the line, but the transmission buckled under the load of all that torque and repeatedly missed shifts or fell out of gear at higher rpm. This hog is happiest at a much mellower pace.

The Diavel did the best. That fat rear tire hooked up great, allowing the Ducati to carry the front Pirelli through second gear and record the lowest ET. It might not be the most powerful, but the Ducati still serves up plenty of stomp on the dragstrip and is equally capable on a twisty back road.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/7GJYDUIPXRGMTMQKN6ONYOLBOU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MUQLOVLL2ZDGFH25ILABNBXKTI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TNOU5DNE2BC57MFPMGN2EIDXAM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GTCXACQGJ5HAPDTGWUQKDEH44E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/S35YGSEMEZB4BLTDJTSZPF4GLA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5UOT6HPX2JFMRJAX6EH45AR4MQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OKWOJWAKP5EP3OACCRRWPCIX2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)