The idea of a carbon-fiber motorcycle chassis is not a new one, but the idea of mass-production models using the exotic material has always seemed a long way off. But now BMW is working on a range of carbon-fiber motorcycle frames intended to replace traditional metal designs.

The Bavarian firm is already a world leader in the technology needed to mass-produce CFRP components. (That stands for carbon-fiber-reinforced polymers—the technical name for what we normally call carbon-fiber or simply carbon.) BMW's car division already offers full CFRP frames on the electric i3 and hybrid i8 models, and the new 7-Series sedan features a full carbon safety cell. Other firms also make carbon-chassis machines, but most are labor-intensive handmade supercars with price tags to equal the national debt of Guatemala. You can buy a fully carbon BMW, in the form of the i3, for around $40,000.

The ability to use automated production lines to quickly produce CFRP parts is the result of more than a decade’s work, and BMW expects to use an increasing amount of the material across its range in the future. And that includes the two-wheeled variety. New patents filed in Germany reveal that BMW has developed two distinct types of motorcycle frame, both made entirely from CFRP and designed with large-scale production in mind.

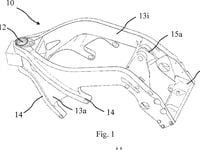

The more exotic of the designs is a beam frame, presumably intended to appear on a future generation of S1000RR. It's visually similar to a conventional aluminum beam frame, but the structure and construction method are quite different.

The firm starts with square-section tubes of carbon fiber, created using a method called “pultrusion” where the fibers are pulled through a bath of resin and through a heated die to create finished components. These tubes are then arranged together around a mold to create the shape of the bike’s frame and engine mounts, with additional layers of carbon-fiber sheet forming the inner and outer walls of the frame’s beams. A steering head and two cross-members are also placed in the mold, and the whole thing is cured under heat and pressure to create the finished chassis. The complete process should be no more time consuming or expensive than the creation of an aluminum beam frame, but the resulting chassis will be lighter and more rigid.

BMW's second frame design is a trellis, more like the steel frames it currently uses on the R-series boxer models. It's been developed to be more adaptable and cheaper than the beam frame.

Again, pultrusion is the main process, but this time it creates simple, straight tubes that are cut to length to create the trellis sections. These are clamped together using junction units, made of either aluminum or carbon fiber, to complete the frame. Changing the lengths and layouts of the tubes gives infinite possibilities when it comes to the resulting chassis dimensions and geometry, and BMW’s patent even suggests that a combination of different materials could be used. Some of the tubes could be metal, for instance, while others are carbon fiber or even simply plastic.

Once again, the whole process isn’t much more complex than the cutting and welding of steel tubes needed to create a conventional trellis frame, but the result should be both lighter and stiffer. Exactly how much lighter the new frames will be compared to existing designs is hard to pin down, but in aerospace applications carbon is often estimated to give up to 30 percent weight saving over comparable aluminum parts.

While we’re all happy to have carbon-fiber cosmetic parts on our bikes, and every racebike is liberally clothed in the stuff, the history of carbon as a structural material on motorcycles isn’t littered with success stories.

Notable efforts to make carbon frames include those of Cagiva in its early ’90s GP bikes and the more recent Ducati Desmosedici GP9, GP10, and GP11 models, with their carbon monocoque chassis. While the early carbon Ducatis won races in the hands of Casey Stoner, few other carbon bikes have had such success, and other riders weren’t able to replicate Stoner’s speed.

Were the problems down to the frames? Some claim that carbon is too rigid, harming the feedback needed by top-level riders or forcing other components, like the forks, to flex instead. However, the truth is that carbon fiber can be as flexible or rigid as a designer wants—many fishing rods are carbon fiber, and they flex like crazy.

If feedback is affected, one theory is that it’s due to the deadening effect of carbon fiber on small vibrations. While it can be as strong and stiff as steel or aluminum, it won’t ring like a bell if struck.

Is that really a limit when it comes to outright performance? The jury is still out on that one. Ducati didn’t see instant improvements when it replaced its carbon frame with aluminum, suggesting its problems lie elsewhere, and Cagiva never had the sort of development budget to be truly competitive, regardless of its choice of frame material.

What’s fairly certain is that a road rider is sure to appreciate the weight savings of a carbon-fiber chassis and is never going to notice the sort of minute feedback differences that may have affected the performance of carbon frames in top-level racing.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/2WF3SCE3NFBQXLDNJM7KMXA45E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/G4MG6OUCJNBSHIS2MVVOTPX65E.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IIGGWFOTOJGB7DB6DGBXCCMTDY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QSTCM6AVEZA5JJBUXNIQ3DSOF4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4I7G625B5DMLF2DVIJDFZVV6M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/B6XD6LS6IVCQPIU6HXDJSM3FHY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ICL63FEDDRDTTMINYICCEYGMDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FCGZHQXRBZFLBAPC5SDIQLVF4I.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WNOB6LDOIFFHJKPSVIWDYUGOPM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X33NU3E525ECRHXLNUJN2FTRKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/6KKT5NNL2JAVBOXMZYS5ZO76YA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/J5RKG5O455GMPGQRF2OG6LRT7A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GX2CIZKQVRH2TATDM26KFG2DAE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZWIDYSAKQZHD5BHREMQILXJCGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CYUHJZCTSJCH3MRAQEIKXK7SCQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LKOFINY56FCXJCANJ5M7ZDQUBY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4NBPDACMWJH63JQYJVK3QRBDZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KKHQHRR3FJGX7H2IPU6RALMWG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5IOFS5JAE5FOXMNA23ZRAVVYUU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CGXQ3O2VVJF7PGTYR3QICTLDLM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)